Book of Abraham

“When we read the Book of Abraham with the reflection that its light has burst upon the world after a silence of three or four thousand years, during which it has slumbered in the bosom of the dead, and been sealed up in the sacred archives of Egypt’s mouldering ruins; when we see there unfolded our eternal being—our existence before the world was—our high and responsible station in the councils of the Holy One, and our eternal destiny; when we there contemplate the majesty of the works of God as unfolded in all the simplicity of truth, opening to our view the wide expanse of the universe, and shewing the laws and regulations, the times and revolutions of all the worlds, from the celestial throne of heaven’s King, or the mighty Kolob, whose daily revolution is a thousand years, down through all the gradations of existence to our puny earth, we are lost in astonishment and admiration, and are led to explain, what is man without the key of knowledge? or what can he know when shut from the presence of his maker, and deprived of conversation with all intelligences of a higher order? Surely the mind of man is just awaking from the deep sleep of many generations, from his thousand years of midnight darkness.”

– Parley P. Pratt (1842)1

The Book of Abraham is believed by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to be “an inspired translation of the writings of Abraham. Joseph Smith began the translation in 1835 after obtaining some Egyptian papyri. The translation was published serially in the Times and Seasons beginning March 1, 1842, at Nauvoo, Illinois.”2

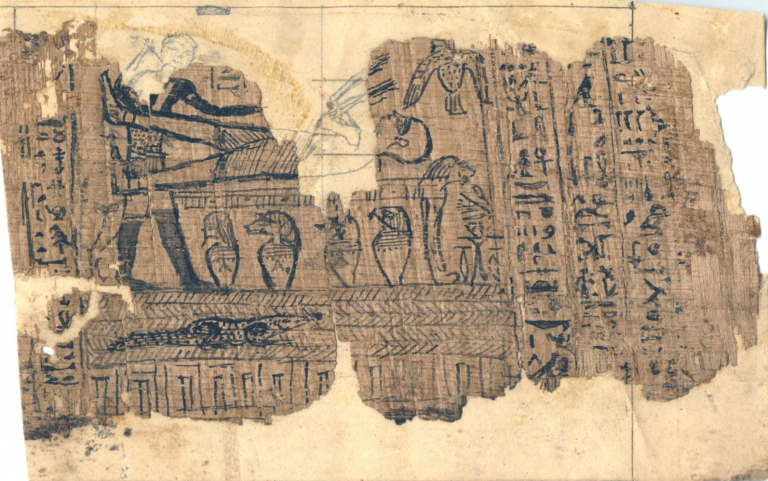

Canonized as scripture by the Church in 1880, the Book of Abraham teaches important doctrinal truths about the Abrahamic covenant and the Plan of Salvation. It also narrates an account of the patriarch Abraham’s near-sacrifice at the hands of his idolatrous kinsmen in Ur of the Chaldees, his journey into Canaan, the covenant he made with God, and his vision of the pre-mortal world and the Creation. Appended to the Book of Abraham are three facsimiles that illustrate the text and explain some of its cosmology.

Considerable controversy surrounds the Book of Abraham. Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the three facsimiles have come under scrutiny by Egyptologists, and in 1967 some fragments of the papyri once possessed by Joseph Smith were recovered and published. These papyri fragments were translated and found not to contain the Book of Abraham but Egyptian funerary texts known as the Book of Breathings and the Book of the Dead.3 The relationship between these papyri fragments and the Book of Abraham is a matter of ongoing study and debate.

Since at least the 1960s, Latter-day Saint scholars have explored the text of the Book of Abraham to see what clues might exist that situate it in a plausible ancient setting.4 They have also argued for the legitimacy of Joseph Smith’s interpretation of the facsimiles as Egyptological knowledge has progressed. These efforts, in conjunction with ongoing progress in the fields of Egyptology and Near Eastern archaeology, have uncovered numerous points of convergence between the text and the ancient world. Evidence for Joseph Smith’s interpretation of the facsimiles has also come to light. These various lines of evidence do not “prove” the Book of Abraham is true, but they do help us situate the text in a plausible ancient environment, inform how we read the text, and positively impact our evaluation of Joseph Smith’s claims to prophetic inspiration.

To aid readers in these endeavors, Book of Mormon Central will be publishing a series of short essays as part of its new Pearl of Great Price Central research initiative. This series will (1) highlight some of the more noteworthy convergences between the Book of Abraham and the ancient world, (2) explore how Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles harmonize with modern scholarship, and (3) provide an overview on what is known about the coming forth and translation of the Book of Abraham.

These short articles aim to provide readers with useful insights as they explore this rich and rewarding text and to bolster confidence in Joseph Smith’s claim to have translated the writings of Abraham. The articles have been kept deliberately short so as to not overwhelm readers with sometimes technical and arcane information about ancient languages and cultures. For those wanting to dive deeper into these matters, suggested readings are provided at the end of each article.

In addition, a non-exhaustive bibliography has been assembled to provide readers with a sense of the scope of research Latter-day Saints have devoted to the Book of Abraham over the span of many years and to make this research readily accessible for interested readers of this book of scripture.

Finally, a newly reformatted study edition of the Book of Abraham has been prepared to help facilitate a close, engaged reading of the text. While paying attention to reliable scholarship is important in approaching the Book of Abraham “by study and also by faith” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:118), it is crucial not to overlook the text itself.

There is still much we do not know when it comes to how precisely Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham.5 There are likewise still remaining questions surrounding Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles and the ancient world of Abraham. This project does not presume to answer all the questions people may have about the Book of Abraham, its coming forth, and its contents. Rather, it hopes to equip seekers and honest questioners with the best, most reliable scholarly resources available and provide answers or insights where possible.

For readers wanting more coverage on these and related topics, two good places to start are the Church’s Gospel Topics essay “Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham” and the book An Introduction to the Book of Abraham by Latter-day Saint Egyptologist John Gee. High resolution images of Joseph Smith’s surviving Egyptian papyri fragments, the Book of Abraham manuscripts, and related documents can be viewed online at the Joseph Smith Papers Project website.

Footnotes

1Parley P. Pratt, “Editorial Remarks,” Millennial Star 4, no. 3 (August 1, 1842): 70–71.

2The Pearl of Great Price, Introduction.

3 Translations of the papyri can be found in Michael D. Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathing: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002); Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2010).

4 The pioneering scholar behind this effort was Hugh Nibley, who wrote extensively on the Book of Abraham. See Hugh Nibley, Abraham in Egypt, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000); The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005); An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2009); Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2010).

5 “No known first-person account from Joseph Smith exists to explain the translation of the Book of Abraham, and the scribes who worked on the project and others who claimed knowledge of the process provided only vague or general reminiscences. Smith’s journal suggests that he and his clerks saw their study of the papyri as being divided into two separate but related projects: their attempts to decipher and systematize the Egyptian language and their work on the Book of Abraham text. The journal did not, however, specify the mechanics of either project or how the two projects related to one another.” Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., “Volume 4 Introduction: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts,” in The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2018), xxiii–xxiv; See further Kerry Muhlestein and Megan Hansen, “‘The Work of Translating’: The Book of Abraham’s Translation Chronology,” in Let Us Reason Together: Essays in Honor of the Life’s Work of Robert L. Millet, ed. J. Spencer Fluhman and Brent L. Top (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: 2016), 139–162.