Book of Abraham Insight #8

The Book of Abraham contains the following account of the discovery of Egypt by the descendants of Ham: “The land of Egypt [was] first discovered by a woman, who was the daughter of Ham, and the daughter of Egyptus” (Abraham 1:23). This woman “discovered the land [when] it was under water, who afterward settled her sons in it; and thus, from Ham, sprang that race which preserved the curse in the land.” Thereafter “first government of Egypt” was established by “Pharaoh, the eldest son of Egyptus, the daughter of Ham” (vv. 24–25).

This genealogy in the Book of Abraham reflects the names of the characters as printed in the 1 March 1842 issue of the Times and Seasons.1 Two of the names, however, are rendered differently in the 1835 Kirtland-era Book of Abraham manuscripts. The name of Ham’s wife in all three Kirtland-era manuscripts is either “Zep-tah” or “Zeptah.”2 Additionally, the name of Ham and Zeptah’s daughter is Egyptes in the Kirtland-era manuscripts, as opposed to Egyptus.3

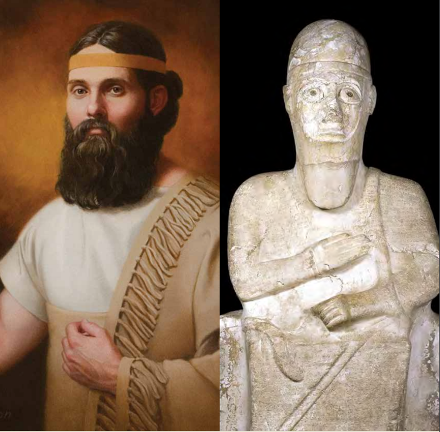

The name Zeptah stands out since it could very plausibly be a rendering of the Egyptian name Siptah (sꜣ ptḥ), meaning “son of [the god] Ptah.”4 This name, as well as its feminine equivalent “daughter of [the god] Ptah” (sꜣt ptḥ), is attested during the likely time of Abraham (circa 2,000–1,800 BC).5 It is also the name of an Egyptian king who lived many centuries after Abraham.6 The spelling of the name with a Z instead of an S is not a problem for the Book of Abraham, since in the Egyptian language of Abraham’s time “these two consonants were pronounced the same, like English s as in set.” They were “essentially one consonant [in the Egyptian language of this time], and could often be written interchangeably.”7

The name Egyptes/Egyptus is clearly related to the name Egypt, which comes from the Greek Aigyptos (Latin: Aegyptus). Aigyptos is a rendering of one of the Egyptian names for the ancient city of Memphis, which contains the theophoric Ptah element (ḥwt-kꜣ-ptḥ; literally “the estate of the Ka [spirit] of [the god] Ptah”).8 Since Egyptes/Egyptus is a Greek name that would be anachronistic for Abraham’s day, it might reflect the work of ancient scribes transmitting the text who “updated” the name centuries later. This may have been the case with the name Zeptah as well.9

We don’t know for certain why Joseph Smith changed the names Zeptah and Egyptes when he published the Book of Abraham in 1842. The change from Egyptes to Egyptus might easily be explained as the modern scribe(s) for the Book of Abraham originally mishearing the name and being corrected later.10 The change from Zeptah to Egyptus is harder to explain. It could have been the result of scribe Willard Richards incorrectly copying the name shortly before the Book of Abraham was published.11 Another possibility is that the Prophet or one of his scribes who read through the text of the Book of Abraham beforehand substituted a more familiar name for the less familiar one to make it more consistent with other names in the text.12

But why would a woman have a man’s name like Zeptah? One possibility is that the name was confused by ancient scribes copying the text after Abraham’s lifetime. This seems to have happened before to other ancient Egyptian figures, including, potentially, a male Egyptian king named Netjerkare Siptah who lived before Abraham’s lifetime and who appears to have been mistaken as a beautiful woman for almost 2,000 years because of ancient scribal mistakes.13 Perhaps a similar problem happened when the Book of Abraham was copied over the centuries.

Alternatively, Egyptologist Vivienne G. Callender argues that Netjerkare Siptah was in fact a woman ruler named Neitikrety Siptah, despite the masculine form of Siptah in her name.

Perhaps the presence of the phrase, ‘Son of Ptah’, . . . may have been a specific tribute to the Memphite god, who was particularly prominent at this time. The masculinity of this name . . . is not a problem for a feminine ruler, because the masculine filiation, sꜣ Rˁ [son of Re], was later used by other female rulers, such as Sobekneferu, who fluctuated between using male and female nomenclature. Sobekneferu, Hatshepsut and Tausret all used various forms of masculine display or titulary when they were rulers, so, if she had been a female ruler, perhaps Neit-ikrety may have done the same, and the title, sꜣ ptḥ, may have been used to indicate that her monarchy was different from that of the other rulers who used sꜣ Rˁ in the Old Kingdom.14

If this argument is correct, then we would have an attested ancient Egyptian female personality using precisely the same masculine name as in the Book of Abraham.

While we may not be able to currently answer these questions entirely, what can be said is that the name Zeptah in the Book of Abraham is, arguably, authentically Egyptian.

Further Reading

Hugh Nibley, “A Pioneering Mother,” in Abraham in Egypt, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2000), 466–556.

Footnotes

1 “Book of Abraham,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 705.

2 Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2018), 199, 211, 227.

3 Jensen and Hauglid, The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 199, 211, 227.

4 The god Ptah was “one of the oldest of Egypt’s gods,” with evidence for his worship as early as the Early Dynastic Period (circa 3,100–2,700 BC). Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 123; Jacobus Van Dijk, “Ptah,” in The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion, ed. Donald B. Redford (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2002), 322. Among his other attributes, Ptah was imagined early on as a craftsman and creator god, and was later associated with Nun and Nunet, the godly personifications of the primeval waters of creation. Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2002), 182. This may have significance for the Book of Abraham’s depiction of Egypt being “under water” when it was first discovered by Zeptah and her family.

5 Hermann Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, 3 vols. (Glückstadt: J. J. Augustin Verlag, 1935), 1:282, 288.

6 Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004), 181; Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of Ancient Egypt (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 243–244; Ronald J. Leprohon, The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 124.

7 James P. Allen, Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, 3rd rev. ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 19.

8 See the discussion in Hugh Nibley, Abraham in Egypt, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2000), 466–556, esp. 526–539; cf. Manetho, Aegyptiaca (I.5).

9 “The transmission of [ancient] documents allowed for updating of language,” including place names and personal names. John H. Walton and D. Brent Sandy, The Lost World of Scripture: Ancient Literary Culture and Biblical Authority (Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic, 2013), 32. This is seen in the Bible where the names of two of king Saul’s sons are given as Ishbosheth and Mephibosheth in 2 Samuel but are rendered Eshbaal and Meribaal in 1 Chronicles. While not all scholars agree on the meaning of this divergence, many think the baal (as in the god Baal) element was deliberately replaced by scribes with bosheth (the Hebrew word for “shame”). See the discussion in Michael Avioz, “The Names Mephibosheth and Ishbosheth Reconsidered,” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 32, no. 1 (2011): 11–20. City names might also be updated by scribes so that the older name is given along with the name the city was known by at the time the scribe was working. This is seen in Judges 18:29: “They named the city Dan, after their ancestor Dan, who was born to Israel; but the name of the city was formerly Laish.” Examples of Egyptian scribes actively “updating” and “expanding” the language older texts, including names and epithets, can also be cited. See for instance Emile Cole, “Interpretation and Authority: The Social Functions of Translation in Ancient Egypt,” PhD dissertation (2015), 167–171, 201–205; and the discussion in Emily Cole, “Language and Script in the Book of the Dead,” in Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt, ed. Foy Scalf (Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute, 2017), 41–48.

10 Jensen and Hauglid, The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 292n78.

11 Jensen and Hauglid, The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 261.

12 One author has suggested that the name was changed “for consistency,” since Joseph had already “translated or transliterated the name of the country as Egypt.” This makes sense, because “Joseph Smith was translating the papyrus into English for readers who were already commonly familiar with this nomenclature.” James R. Clark, The Story of the Pearl of Great Price (Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1955), 127, emphasis in original. Another possibility is that the change was made because the Prophet or one of his clerks had come to view Zeptah and Egytpes as the same person. The story seems to still work if they are viewed as the same person, but the textual history makes it seem more likely these are two different women. For another proposed explanation for this change, see Brent Lee Metcalfe, “The Curious Textual History of ‘Egyptus’ the Wife of Ham,” The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 34, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2014): 1–11.

13 Kim Ryholt, “The Late Old Kingdom in the Turin King-list and the Identity of Nitocris,” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache 127 (2000): 87–100.

14 Vivienne G. Callender, “Queen Neit-ikrety/Nitokris,” in Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010/2011, ed. Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, and Jaromír Krejčí (Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, 2011), 256.