Book of Abraham Insight #17

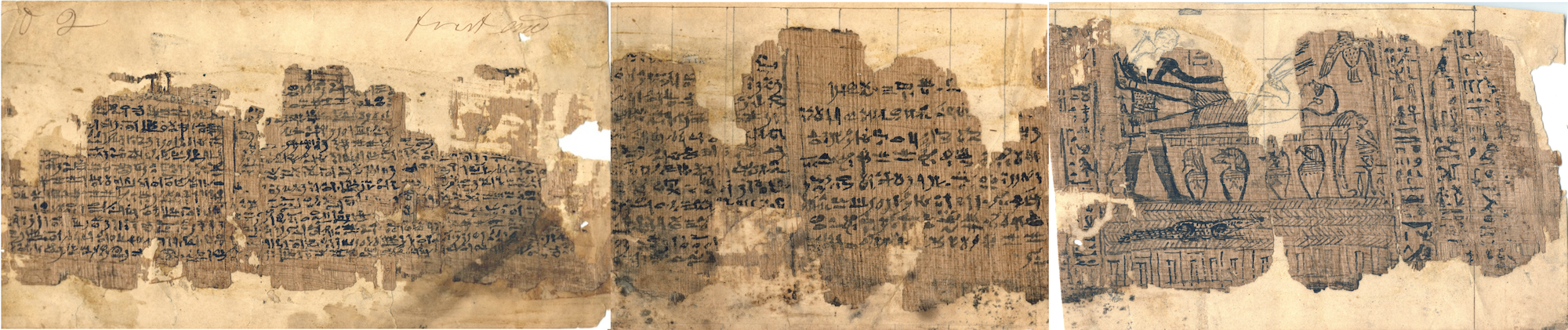

One of the more memorable contributions of the Book of Abraham is its depiction of Kolob (Abraham 1:3–4, 9, 16; Facsimile 2, Fig. 1). According to the Book of Abraham, Kolob is characterized by the following features:

- It is a star.1

- It is a “great [star]” and a “governing one.”

- It is “near unto [God]” or “nigh unto the throne of God.”

- It was used to tell relative time (“one revolution [of Kolob] was a day unto the Lord, after his manner of reckoning, it being one thousand years according to the time appointed unto that whereon thou [Abraham] standest”).

- It “signify[ed] the first creation, nearest to the celestial, or the residence of God. First in government, the last pertaining to the measurement of time. The measurement according to celestial time, which celestial time signifies one day to a cubit.”

Latter-day Saints have long been interested in Kolob for its doctrinal and potential cosmological significance.2 The opening words to the beloved Latter-day Saint hymn “If You Could Hie to Kolob” written by W. W. Phelps was, of course, inspired by Kolob in the Book of Abraham.3

In recent years, spurred on by promising discoveries in Egyptology and Near Eastern archaeology, some Latter-day Saint scholars have sought to situate Kolob in the ancient world. Although there are still many uncertainties, a few points in favor of Kolob being authentically ancient can be affirmed with reasonable plausibility.

First is the matter of the etymology of the name Kolob. One of the more common proposals is that the name derives from the Semitic root qlb, meaning “heart, center, middle,” and is thus related to the root qrb, meaning “to be near, close.”4 This explanation is enticing because it works well as a pun on the name provided for Kolob within the Book of Abraham itself: “the name of the great one is Kolob [qlb; “middle, center”], because it is near [qrb] unto me [i.e. the Lord]” (Abraham 3:3).5 The drawback to this theory, however, is that qlb as a Semitic word is only attested as far back as Arabic, which is considerably later than Abraham’s time.6 That being said, there are conjectural Afroasiatic roots that could potentially place this word in Abraham’s day.7

Another promising proposal is that Kolob derives from the Semitic root klb, meaning “dog.”8 This theory has been circulating since at least the early twentieth century, when a non-Latter-day Saint named James E. Homans (writing under the pseudonym R. C. Webb) postulated this idea in 1913.9 This, in turn, has prompted some to identify Kolob with Sirius, the dog-star.10 Known as Sopdet (or Sothis in Greek) in ancient Egypt, Sirius held both mythological as well as calendrical significance to the ancient Egyptians. Usually associated with the goddesses Isis and Hathor, the star Sirius “had a special role because its heliacal rising coincided with the ideal Egyptian New Year day that was linked with the onset of the Nile inundation.”11

Both Sirius and Kolob share a number of overlapping characteristics, including:

While these convergences are compelling, the main drawback to this theory is that, as far as is currently attested, klb (“dog”) appears to have been used anciently to identify the constellation Hercules as opposed to Canis Major (which contains Sirius).16 However, by the Greco-Roman period of Egyptian history (the period that the Joseph Smith Papyri and facsimiles date to) there is evidence that Sirius (Isis-Sothis) was “represented as a large dog,”17 and it is possible that this representation pre-dates Abraham’s day, although this point is disputed among Egyptologists.18 At this point, the identification of Kolob as Sirius is promising but remains unproven.

Conceptually, the way Kolob is depicted in the Book of Abraham interplays well with ancient Egyptian cosmology. As explained by Egyptologist John Gee:

The ancient Egyptians associated the idea of encircling something (whether in the sky or on earth) with controlling or governing it, and the same terms are used for both. Thus, the Book of Abraham notes that “there shall be the reckoning of the time of one planet above another, until thou come nigh unto Kolob, . . . which Kolob is set nigh unto the throne of God, to govern all those planets which belong to the same order as that upon which thou standest” (Abraham 3:9; emphasis added). The Egyptians had a similar notion, in which the sun (Re) was not only a god but the head of all the gods and ruled over everything that he encircled. Abraham’s astronomy sets the sun, “that which is to rule the day” (Abraham 3:5), as greater than the moon but less than Kolob, which governs the sun (Abraham 3:9). Thus, in the astronomy of the Book of Abraham, Kolob, which is the nearest star to God (Abraham 3:16; see also 3, 9), revolves around and thus encircles or controls the sun, which is the head of the Egyptian pantheon.19

While questions about the identification of Kolob still remain, there are some very tantalizing pieces of evidence that, when brought together, reinforce the antiquity of this astronomical concept unique to the Book of Abraham.

Further Reading

John Gee, “Abrahamic Astronomy,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 115–120.

Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2010), 250–260.

John Gee, William J. Hamblin, and Daniel C. Peterson, “‘And I Saw the Stars’: The Book of Abraham and Ancient Geocentric Astronomy,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 1–16.

Footnotes

1 The Book of Abraham tends to conflate “star” with “planet,” leading some Latter-day Saints to speak of Kolob as a planet or world. See for instance Brigham Young, “Territory of Utah: Proclamation, for a Day of Praise and Thanksgiving,” in Journals of the House of Representatives, Council, and Joint Sessions of the First Annual and Special Sessions of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT: Brigham Young, 1852), 166; John Taylor, “Origins, Object, and Destiny of Woman,” The Mormon 3, no. 28 (August 29, 1857); Orson Pratt, “Millennium,” The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 28, no. 36 (September 8, 1866): 561; Bruce L. Christensen, “Media Myths and Miracles,” BYU Devotional, November 8, 1994. While confusing for modern readers, this conflation makes sense from an ancient perspective, as discussed in John Gee, William J. Hamblin, and Daniel C. Peterson, “‘And I Saw the Stars’: The Book of Abraham and Ancient Geocentric Astronomy,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 11.

2 B. H. Roberts, A New Witness for God (Salt Lake City, UT: George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1895), 446–448; George Reynolds and Janne M. Sjodahl, Commentary on the Pearl of Great Price (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret News Press, 1965), 308–312; The Pearl of Great Price Student Manual (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2017), 71–73, 78, 81.

3 Hymn #284 in the current hymnal of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; first published in 1856 under the title “There is No End,” Deseret News (November 19, 1856), 290.

4 Janne M. Sjodahl, “The Book of Abraham,” Improvement Era 16, no. 4 (February 1913): 329; “The Word ‘Kolob’,” Improvement Era 16, no. 6 (April 1913): 621; Sidney B. Sperry, Ancient Records Testify in Papyrus and Stone (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1938), 86; Robert F. Smith, “Some ‘Neologisms’ From the Mormon Canon,” in Conference on the Language of the Mormons (Provo, UT: Language Research Center, Brigham Young Uniersity, 1973), 64; Michael D. Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus . . . Twenty Years Later,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1994), 8; “Teaching the Book of Abraham Facsimiles,” Religious Educator 4, no. 2 (2003): 121; Richard D. Draper, S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes, The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005), 289–290; Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2010), 250–251.

5 The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, ed. John A. Brinkman et al (Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute, 1982), s.v. qerbu; Jeremy Black, Andrew George, Nicholas Postgate, eds., A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2000), 288.

6 The closest attested word in Abraham’s day to the Arabic qalb would probably be the Old Akkadian qabla or qablu (qablītu), meaning “in the middle” or “middle part.” The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, s.v. qabla, qablītu; Black, George, Postgate, A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, 281.

7 See Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 32, who cites the reconstructed Afroasiatic root ḳlb/ḳrb for the Egyptian and Akkadian cognates qꜣb (“interior”) and qerbum (“inside”), respectively; compare James P. Allen, The Ancient Egyptian Language: A Historical Study (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 35.

8 The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, s.v. kalbu; Black, George, Postgate, A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, 142.

9 Robert C. Webb [James E. Homans], “A Critical Examination of the Fac-Similies in the Book of Abraham,” Improvement Era 16, no. 5 (March 1913): 445; cf. Joseph Smith as a Translator (Salt Lake City, UT: The Deseret News Press, 1935), 102–103.

10 Webb, “A Critical Examination of the Fac-Similies in the Book of Abraham,” 445; Joseph Smith as a Translator, 103; Nibley and Rhodes, One Eternal Round, 251–252.

11 Joachim Frederich Quack, “Astronomy in Ancient Egypt,” in The Oxford Handbook of Science and Medicine in the Classical World, ed. Paul T. Keyser and John Scarborough (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018), 62. See also Raymond O. Faulkner, “The King and the Star-Religion in the Pyramid Texts,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 25, no. 3 (July 1966): 157–160; Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 167–168; Jay B. Holberg, Sirius: Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky (Berlin: Springer, 2007), 3–14.

12 One of the ancient Egyptian epithets for Sopdet/Sirius was wˁbt swt or “pure of thrones” in Pyramid Text 442 (§822a) and Pyramid Text 504 (§1082d). The image of the Throne of God in the heavens is commonplace in the Bible (e.g. Psalm 11:4; 103:19; Matthew 5:34; 23:22; Revelation 4:1–2, 5–6).

13 “[Seirios] originally was employed to indicate any bright and sparkling heavenly object, but in the course of time became a proper name for this brightest of all the stars” (Richard Hinckley Allen, Star-Names and Their Meanings [New York, NY: G. E. Stechert, 1899], 120). “Greek writers made special reference to Sirius, the brilliant star in the constellation [Canis Major]. The name has been derived from Seirios, ‘sparkling.’ This term was first employed to indicate any bright sparkling object in the sky, and was also applied to the Sun. But after a time, the name was given to the brightest of all stars” (Charles Whyte, The Constellations and their History [London: Charles Griffin, 1928], 231–232). “[Sirius] is the brightest of the fixed stars. . . . [and] has been throughout human history the most brilliant of the permanent fixed stars” (Robert Burnham, Jr., Burnham’s Celestial Handbook: An Observer’s Guide to the Universe Beyond the Solar System [New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1978], 1:387, 390). “Among the brightest stars of the northern winter sky, Sirius is prominent as the principal star of the constellation Canis Major, Latin for the Greater Dog” (Holberg, Sirius, 15).

14 As “the star which fixes and governs the periodic return of the year” (James Bonwick, Egyptian Belief and Modern Thought [London: K. Paul & Co., 1878], 113) and the annual inundation of the Nile, Sirius (specifically its godly manifestation as Hathor/Isis) bore the epithets “Lady of the beginning of the year, Sothis, Mistress of the stars” (nbt tp rnpt spdt ḥnwt ḫꜣbꜣ.s) and “Sothis in the sky, the Female Ruler of the stars” (spdt m pt ḥqꜣt n[t] ḫꜣbꜣ.s). Barbara A. Richter, The Theology of Hathor of Dendera: Aural and Visual Scribal Techniques in the Per-Wer Sanctuary (Atlanta, GA: Lockwood Press, 2016), 4n8, 96.

15 Richter, The Theology of Hathor of Dendera, 4n8, 96–97, 173, 185; Holberg, Sirius, 14. One late Egyptian text describes Sirius as “[the one] who created those who created us” (r-ir qm nꜣ ỉỉr qm.n), making the star the supreme creator, as it were. “She is Sirius and all things were created through her” (spt tꜣy mtw.w ỉr mdt nb r-ḥr.s). Wilhelm Spiegelberg, Der Ägyptische Mythus vom Sonnenauge (Strassburg: R. Schutz, 1917), 28–29.

16 The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, s.v. kalbu; Douglas B. Miller and R. Mark Shipp, An Akkadian Handbook: Paradigms, Helps, Glossary, Logograms, and Sign List (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996), 55; Black, George, Postgate, A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, 142. In Syriac, kelb does refer to Sirius, although this language post-dates Abraham considerably, and so it is uncertain if this identification extends as far back as the Middle Bronze Age in earlier proto-Semitic forms. R. Payne Smith, A Compendious Syriac Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1903), 215. Consider also the Akkadian kalbu ezzu ša Enlil (“the fierce dog of Enlil”) in Hayim Tawil, Akkadian Lexicon Companion for Biblical Hebrew: Etymological, Semantic and Idiomatic Equivalence with Supplement on Biblical Aramaic (Jersey City, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 2009), 164.

17 Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, 168; Marjorie Susan Venit, Visualizing the Afterlife in the Tombs of Graeco-Roman Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 183–184, 186, 192–193; Catlín E. Barrett, Egyptianizing Figurines from Delos: A Study in Hellenistic Religion (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 187–189.

18 Barrett, Egyptianizing Figurines from Delos, 187; Laszlo Kakosy, “Sothis,” in Lexikon der Agyptologie, ed. Wolfgang Helck and Eberhard Otto (Wiesbaden: Harrosowitz Verlag, 1986), 5:1115.

19 John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 116–117; compare Kerry Muhlestein, “Encircling Astronomy and the Egyptians: An Approach to Abraham 3,” Religious Educator 10, no. 1 (2009): 37–43.