Book of Moses Essay #61

Moses 3:9

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

One thing that has always perplexed readers of Genesis is the location of the two special trees in the Garden of Eden. The Hebrew phrase corresponding to “in the midst” means literally “in the center.” Although scripture initially applies the phrase “in the midst” only to the Tree of Life,1 the Tree of Knowledge is later said by Eve to be located there, too.2

Elaborate explanations have been advanced as attempts to describe how both the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge could share the center of the Garden.3 For example, it has been suggested that these two trees were actually different aspects of a single tree,4 that they shared a common trunk,5 or were somehow intertwined.6

The subtle conflation of the location of two trees in the Genesis account seems intentional, preparing readers for the confusion that later ensues in the dialogue between Eve and the serpent.7 The dramatic irony of the story is heightened by the fact that while the reader is informed about both trees, Adam and Eve are only told specifically about the Tree of Knowledge. In later Essays that recount the story of the Fall, we will see how Satan exploits their ignorance to his advantage.

A brief review of the symbolism of the “sacred center” in ancient thought will help clarify the important roles that the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge played “in the midst” of the Garden of Eden.8

The Hierocentric Symbolism of the “Sacred Center”

Hugh Nibley, following Eric Burrows, defined “the term ‘hierocentric’ as that which best describes those cults, states, and philosophies that were oriented about a point believed to be the exact center and pivot of the universe.”9

Such sacred centers, described in different cultures, often coincide with the location of a “mountain or artificial mound and a lake or spring from which four streams flowed out to bring the life-giving waters to the four regions of the earth. The place was a green paradise, a carefully kept garden, a refuge from drought and heat.”10 A version of this perspective is reflected biblically in the layout of the Garden of Eden and the temple,11 as well as in the geography of later stories and prophecies of divinely directed scatterings and gatherings of Israel and other peoples.12

Explaining the choice of a tree to represent the concepts of life, earth, and heaven, Stordalen writes:

Every green tree would symbolize life, and a large tree—rooted in deep soil and stretching towards the sky—potentially makes a cosmic symbol.13 In both cases, it becomes a “symbol of the center.”14

The temple, described by Isaiah as “the mountain of the Lord’s house,”15 is likewise a symbol of the center. In ancient Israel, the holiest spot on earth was believed to be the Foundation Stone in front of the Ark within the Holy of Holies of the temple at Jerusalem. To the Jews, “it was the first solid material to emerge from the waters of creation,16 and it was upon this stone that the Deity effected creation.”17 As a famous passage in the Midrash Tanhuma states:

Just as a navel is set in the middle of a person, so the land of Israel is the navel of the world. Thus it is stated (in Ezekiel 38:12): “Who dwell on the navel of the earth.” The land of Israel sits at the center of the world; Jerusalem is in the center of the land of Israel; the sanctuary is in the center of Jerusalem; the Temple building is in the center of the sanctuary; the ark is in the center of the Temple building; and the foundation stone, out of which the world was founded, is before the Temple building.18

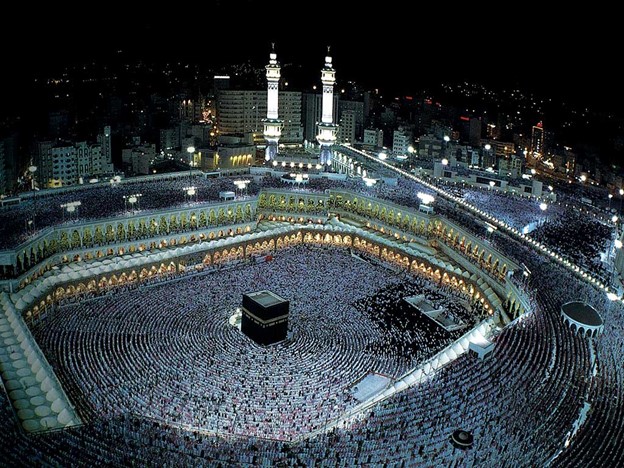

In the symbolism of the sacred center, the circle is generally used to represent heaven, while the square signifies earth. Among other things, the intersection of the circle and square can be seen as depicting the coming together of heaven and earth in both the sacred geometry of the temple and the soul of the seeker of Wisdom.19 For example, the above photograph shows the sacred mosque of Mecca during the peak period of hajj.20 As part of the ritual of tawaf, hajj pilgrims enact the symbolism of the circle and the square as they form concentric rings around the rectangular Ka’bah.21 Islamic tradition says that near this location Adam had been shown the worship place of angels, which was directly above the Ka’bah in heaven,22 and that he was commanded to build a house for God in Mecca where he could, in likeness of the angels, “circumambulate … and offer prayer.”23

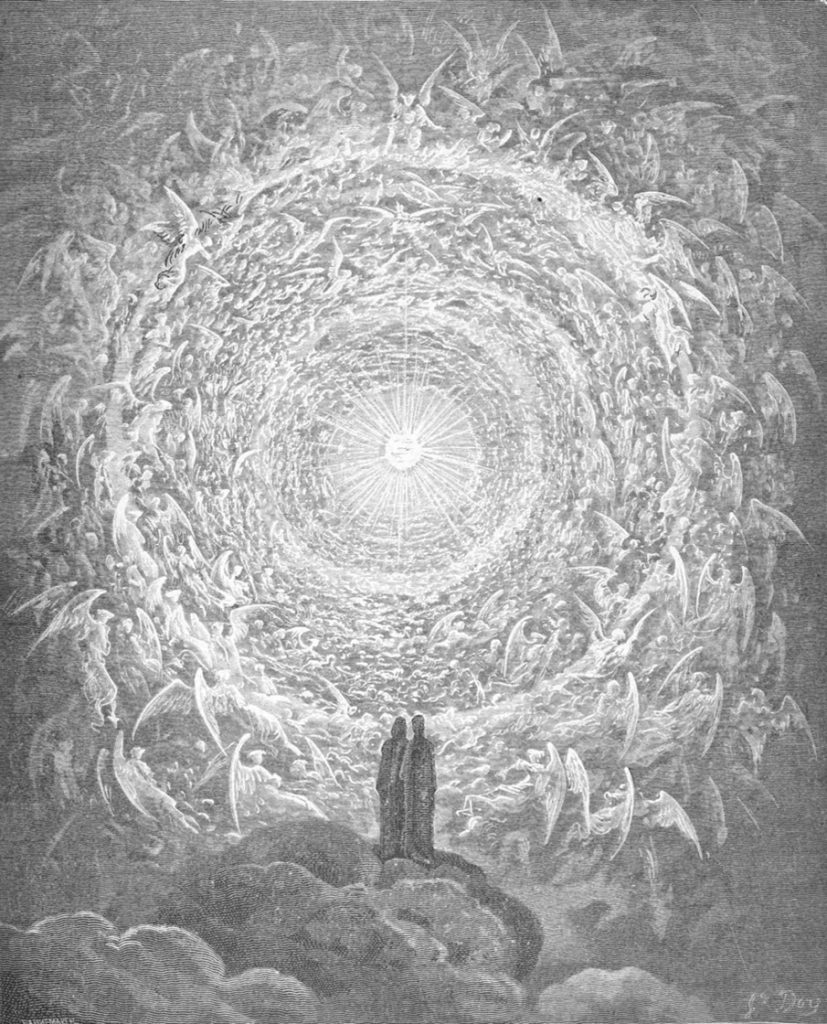

Above we see Gustave Doré’s famous illustration of the “empyrean heaven.”24 This is a representation of the highest heaven as a realm lighted by the pure fire of God’s glory.25 Since the sacred center is located in heaven rather than earth, it is shown as a circle rather than a square. The heavenly throne is, in the words of Lehi, “surrounded with numberless concourses of angels in the attitude of singing and praising their God.”26 Nibley points out: “A concourse is a circle. Of course [numberless] concourses means circles within circles and reminds you of dancing. And what were they doing? Surrounded means ‘all around.’ … It was a choral dance.”27

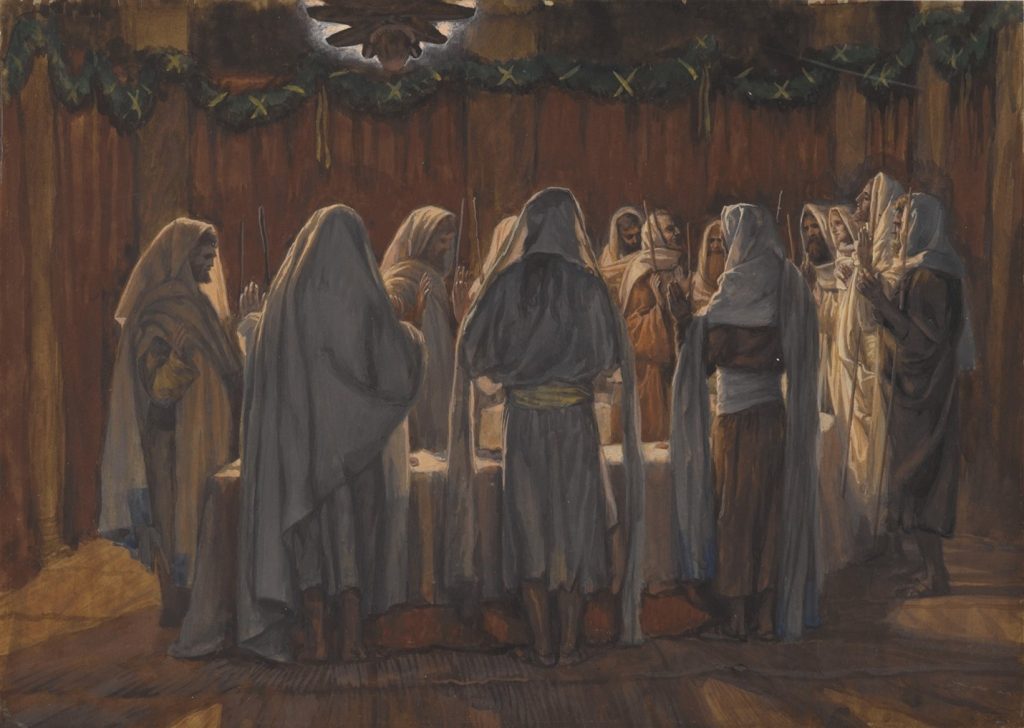

A related pattern was reenacted in ancient prayer circles. For example, describing the connection between the earthly and the heavenly realms in the quorum of ten men forming a Jewish minyan for prayer, Kogan writes: “On one level, the body that is formed below, the actual minyan, is entered by the Shekinah (the supernal holiness), and is thus the point of contact between God and Israel. Simultaneously, the minyan formed in the proper manner below unifies the heavenly realm above.”28

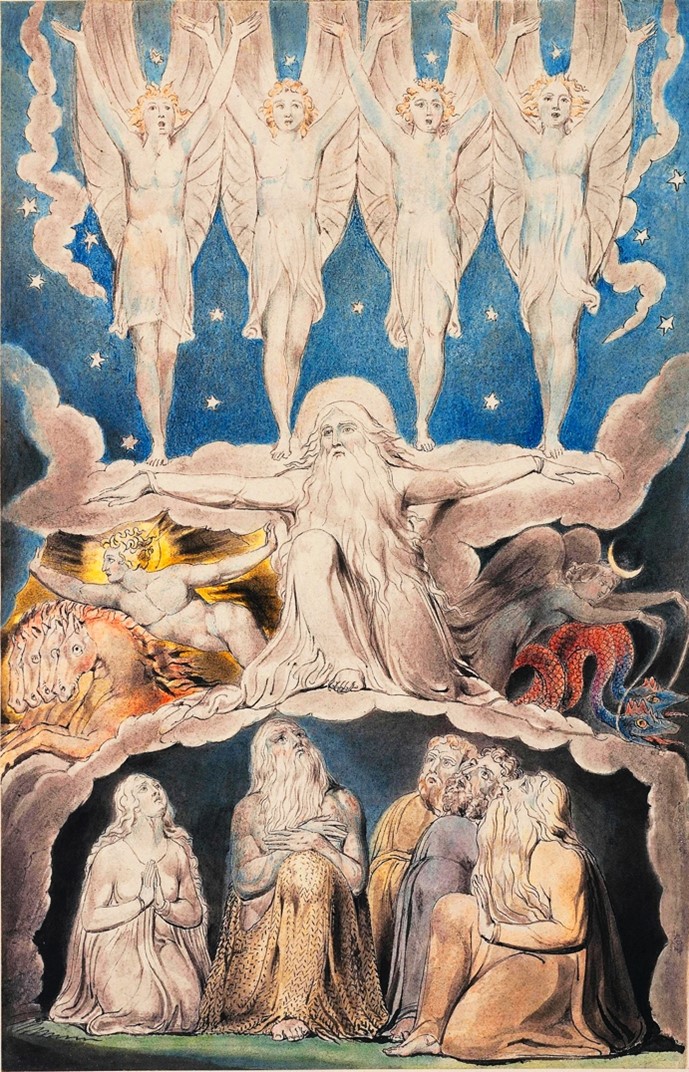

As shown in this figure, the sacred center does not ultimately represent some abstract epitome of goodness, nor merely a ceremonial altar or throne, but God Himself.

The Acts of John records that a prayer circle was formed by the apostles, with Jesus at the center: “So he told us to form a circle, holding one another’s hands, and himself stood in the middle.”29

The center is the most holy place, and the degree of holiness decreases in proportion to the distance from that center.30 For example, BYU Professor S. Kent Brown observes how at His first appearance to the Nephites Jesus “stood in the midst of them,”31 and cites other Book of Mormon passages associating the presence of the Lord “in the midst” to the placement of the temple and its altar.32 He also noted a similar configuration when Jesus blessed the Nephite children:

As the most Holy One, [the Savior] was standing “in the midst,” at the sacred center.33 The children sat “upon the ground round about him.”34 When the angels “came down,” they “encircled those little ones about.” In their place next to the children, the angels themselves “were encircled about with fire.”35 On the edge stood the adults. And beyond them was… profane space which stretched away from this holy scene.36

Jesus’ placement of the children so that they immediately surrounded Him—their proximity exceeding even that of the encircling angels and accompanying fire—conveyed a powerful visual message about their holiness: namely, that “whosoever … shall humble himself as this little child, the same is greatest in the kingdom of heaven.”37 Hence, Jesus’ instructions to them: “Behold your little ones.”38

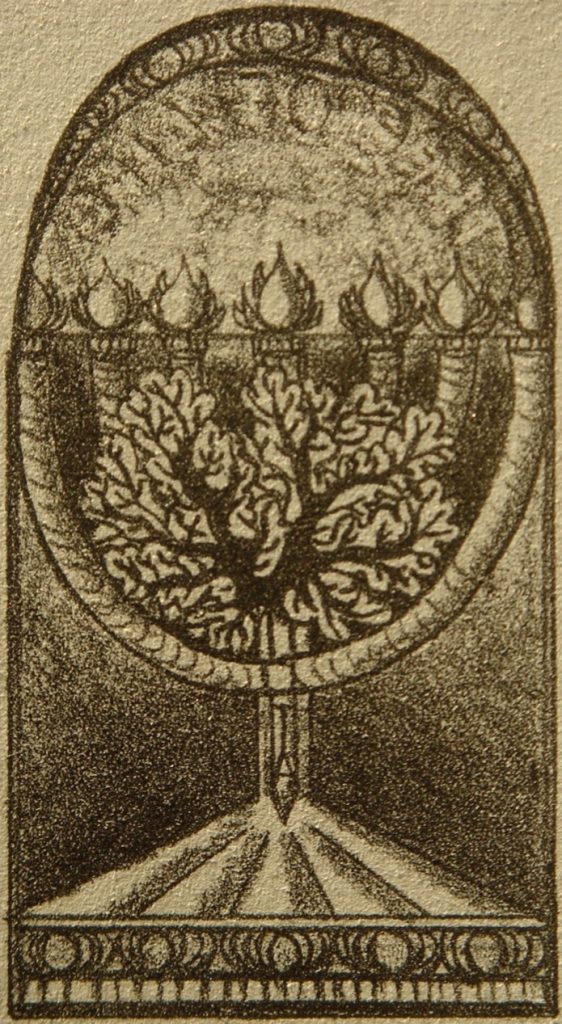

Moses’ vision of the burning bush brings together all three of the symbols of the sacred center we have discussed: the tree, the mountain, and the Lord Himself. Directly tying this symbolism to the Jerusalem Temple, Nicholas Wyatt concludes: “The Menorah is probably what Moses is understood to have seen as the burning bush in Exodus 3.”39 Thus, Jehovah, the premortal Jesus Christ, was represented to Moses as One who dwells at the top of a holy mountain, in the midst of the burning glory of the Tree of Life.

The Tree of Knowledge as the Veil of the Sanctuary

Having explored the concept of the sacred center, we will now return to the question of how both the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge could have shared the center of the Garden of Eden.

Perhaps the most interesting tradition about the placement of the two trees is the Jewish idea that the foliage of the Tree of Knowledge hid the Tree of Life from direct view, and that “God did not specifically prohibit eating from the Tree of Life because the Tree of Knowledge formed a hedge around it; only after one had partaken of the latter and cleared a path for himself could one come close to the Tree of Life.”40

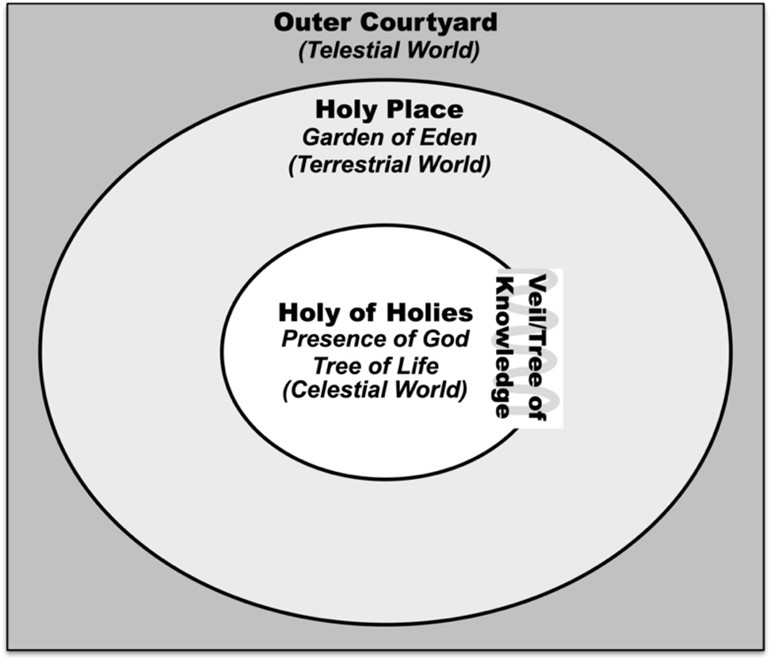

It is in this same sense that Ephrem the Syrian, a brilliant and devoted fourth-century Christian, could call the Tree of Knowledge “the veil for the sanctuary.”41 He pictured Paradise as a great mountain, with the Tree of Knowledge providing a boundary partway up the slopes. The Tree of Knowledge, Ephrem concludes, “acts as a sanctuary curtain [i.e., veil] hiding the Holy of Holies which is the Tree of Life higher up.”42 In addition, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim sources sometimes speak of a “wall” surrounding whole of the Garden, separating it from the “outer courtyard” of the mortal world.43

Consistent with this idea for the layout of the Garden of Eden, Barker sees evidence that in the first temple a Tree of Life was symbolized within the Holy of Holies.44 She concludes that the menorah was both removed from the temple and diminished in stature in later Jewish literature as the result of a “very ancient feud” concerning its significance.45

For those who took the Tree of Life to be a representation of God’s presence within the Holy of Holies, it was natural to see the Tree of Life as the locus of the divine throne:46

[T]he garden, at the center of which stands the throne of glory, is the royal audience room, which only those admitted to the sovereign’s presence can enter.47

Ephrem’s view suggests that the Tree of Life was planted in an inner place so holy that Adam and Eve would court mortal danger if they entered uninvited and unprepared. Though God could minister to them in the Garden, they could not safely enter His world.48

Highlighting the merciful nature of God’s prohibition against eating the fruit of the Tree of Life prematurely, Elder Bruce C. Hafen has explained that the cherubim and a flaming sword were placed to “guard the way of the tree of life” until Adam and Eve completed their probation on earth and learned by experience to distinguish good from evil.49

“Eastward in Eden”

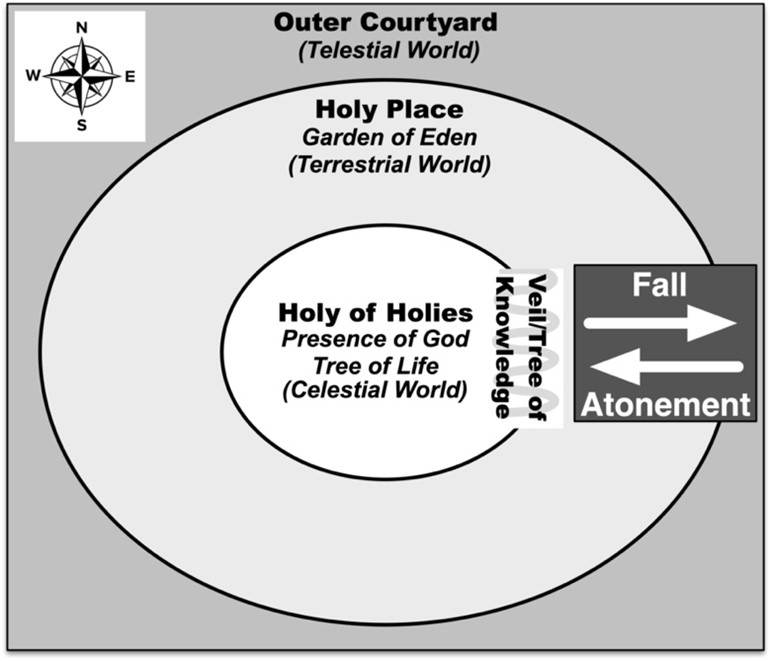

The figure above shows how circular and linear depictions of the layout of the Garden of Eden can be reconciled. Note also how some modern temples feature a linear progression toward a celestial room at the far end of the building,50 whereas in others the movement is in an increasingly inward direction. For example, in the Ogden and Provo Utah temples, “six ordinance rooms [are] surrounded by an exterior hallway” with the “celestial room… in the building’s center.”51

The “eastward” location of the Garden may thus be explained by its position relative to the Creator at the sacred center. Note that the initial separation of Adam and Eve from God occurs when they are removed from His presence to be placed in the Garden “eastward in Eden”52 —that is, east of the “mountain” where, in some representations of the sacred geography of Paradise, He is said to dwell. Such an interpretation also seems to be borne out in later events, as eastward movement is repeatedly associated with increasing distance from God.53 For example, after God’s voice of judgment visits them from the west,54 Adam and Eve experience an additional degree of separation when they were expelled through the Garden’s eastern gate.55 Cain was “shut out from the presence of the Lord” as he resumed the journey eastward to dwell “in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden,”56 a journey that eventually continued in the same direction—“from the east” to the “land of Shinar”—to the place where the Tower of Babel was constructed.57 Finally, Lot traveled east toward Sodom and Gomorrah when he separated himself from Abraham.58

On the other hand, westward movement is often used to symbolize return and restoration of blessings. Abraham’s “return from the east is [a] return to the Promised Land and… the city of ‘Salem,”59 being “directed toward blessing.”60 The Magi of the Nativity likewise came “from the east,” westward to Bethlehem, their journey symbolically enacting a restoration of temple and priesthood blessings that had been lost from the earth.61 Finally, the glorious return of Jesus Christ when He “shall suddenly come to his temple”62 is likewise symbolized by an east-to-west movement: “For as the light of the morning cometh out of the east, and shineth even unto the west, and covereth the whole earth, so shall also the coming of the Son of man be.”63

Conclusion

The central position of the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden provides a parallel to the presence of God in the midst of His temple. The Tree of Knowledge may be a symbol of the protective veil initially concealing the Tree of Life from Adam and Eve. After their transgression of God’s “first commandments,”64 God placed cherubim and a flaming sword to prevent their premature entry into His presence, and sent Adam and Eve away “eastward.” However, God also provided a set of “second commandments”65 that would eventually enable the return of all those who would fully avail themselves of the gift of the Atonement.

This essay is adapted from Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014. English: https://archive.org/details/150904TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses2014UpdatedEditionSReading ; Spanish: http://www.templethemes.net/books/171219-SPA-TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses.pdf, pp. 69–90.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014. English: https://archive.org/details/150904TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses2014UpdatedEditionSReading ; Spanish: http://www.templethemes.net/books/171219-SPA-TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses.pdf, pp. 69–90.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1951. “The hierocentric state.” In The Ancient State, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 10, 99-147. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991.

References

al-Tabari. d. 923. The History of al-Tabari: General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood. Vol. 1. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. Biblioteca Persica, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1989.

Alexander, P. “3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983. https://eclass.uoa.gr/modules/document/.

Alexander, T. Desmond. From Eden to the New Jerusalem: An Introduction to Biblical Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2008.

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Anderson, Gary A., and Michael Stone, eds. A Synopsis of the Books of Adam and Eve 2nd ed. Society of Biblical Literature: Early Judaism and its Literature, ed. John C. Reeves. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1999.

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Ashraf, Syed Ali. “The inner meaning of the Islamic rites: Prayer, pilgrimage, fasting, jihad.” In Islamic Spirituality 1: Foundations, edited by Seyyed Hossein Nasr, 111-30. New York City, NY: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1987.

at-Tabataba’i, Allamah as-Sayyid Muhammad Husayn. 1973. Al-Mizan: An Exegesis of the Qur’an. Translated by Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi. 3rd ed. Tehran, Iran: World Organization for Islamic Services, 1983.

Barker, Margaret. The Older Testament: The Survival of Themes from the Ancient Royal Cult in Sectarian Judaism and Early Christianity. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 1987.

———. “The holy of holies.” In The Great High Priest: The Temple Roots of Christian Liturgy, edited by Margaret Barker, 146-87. London, England: T & T Clark, 2003.

———. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

Beale, Gregory K. The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God. New Studies in Biblical Theology 1, ed. Donald A. Carson. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004.

Berlin, Adele. Esther. The JPS Bible Commentary, ed. Michael Fishbane. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2001.

Bethge, Hans-Gebhard, and Bentley Layton. “On the origin of the world.” In The Nag Hammadi Library in English, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 170-89. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Bickmore, Barry Robert. Restoring the Ancient Church: Joseph Smith and Early Christianity. Ben Lomond, CA: Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research (FAIR), 1999.

Birrell, Anne. Chinese Mythology: An Introduction. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey. “Moses 6–7 and the Book of Giants: Remarkable Witnesses of Enoch’s Ministry.” In Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses: New Perspectives on Literary, Historical, and Textual Aspects of a Divinely Inspired Work, edited by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, David R. Seely, John W. Welch and Scott Gordon. Orem, UT; Springville, UT; Reading, CA; Toole, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, Book of Mormon Central, FAIR, and Eborn Books, 2021.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary.” In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013. https://rsc.byu.edu/ascending-mountain-lord/tree-knowledge-veil-sanctuary ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfIs9YKYrZE.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

Brinkerhoff, Val. The Day Star: Reading Sacred Architecture. 2 vols. Honeoye Falls, NY: Digital Legends Press, 2009.

Brodie, Thomas L. Genesis as Dialogue: A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary. Oxford, England: Oxford University Pres, 2001.

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Brown, S. Kent. Voices from the Dust: Book of Mormon Insights. Salt Lake City, UT: Covenant Communications, 2004.

Callender, Dexter E. Adam in Myth and History: Ancient Israelite Perspectives on the Primal Human. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2000.

Carroll, James L. “The reconciliation of Adam and Israelite temples.” Studia Antiqua 3, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 83-101.

Cassuto, Umberto. 1944. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 1: From Adam to Noah. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1998.

Colvin, Don F. Nauvoo Temple: A Story of Faith. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2002.

Cowan, Richard O. Temples to Dot the Earth. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1989.

Dolkart, Judith F., ed. James Tissot, The Life of Christ: The Complete Set of 350 Watercolors. New York City, NY: Merrell Publishers and the Brooklyn Museum, 2009.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Drower, E. S. The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1937. Reprint, Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2002.

Eden, Giulio Busi. “The mystical architecture of Eden in the Jewish tradition.” In The Earthly Paradise: The Garden of Eden from Antiquity to Modernity, edited by F. Regina Psaki and Charles Hindley. International Studies in Formative Christianity and Judaism, 15-22. Binghamton, NY: Academic Studies in the History of Judaism, Global Publications, State University of New York at Binghamton, 2002.

Ehat, Andrew F. “‘Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord?’ Sesquicentennial reflections of a sacred day: 4 May 1842.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 48-62. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. “The Hymns on Paradise.” In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 77-195. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

———. ca. 350-363. Hymns on Paradise. Translated by Sebastian Brock. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

Fisk, Bruce N. Do You Not Remember? Scripture, Story, and Exegesis in the Rewritten Bible of Pseudo-Philo. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Ginzberg, Louis, ed. The Legends of the Jews. 7 vols. Translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1909-1938. Reprint, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Giorgi, Rosa. Anges et Démons. Translated by Dominique Férault. Paris, France: Éditions Hazan, 2003.

Guénon, René. Symboles fondamentaux de la Science sacrée. Paris, France: Gallimard, 1962.

Hafen, Bruce C. The Broken Heart. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Hansen, Gerald E., Jr., and Val Brinkerhoff. Sacred Walls: Learning from Temple Symbols. Salt Lake City, UT: Covenant Communications, 2009.

Hennecke, Edgar, and Wilhelm Schneemelcher, eds. New Testament Apocrypha. 2 vols. Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press, 1965.

Herbert, Máire, and Martin McNamara, eds. Irish Biblical Apocrypha: Selected Texts in Translation. Edinburgh, Scotland: T & T Clark, 1989.

Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel, and David Rolph Seely. My Father’s House: Temple Worship and Symbolism in the New Testament. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1994.

Huchel, Frederick M. The Cosmic Ring Dance of the Angels: An Early Christian Rite of the Temple. North Logan, UT: The Frithurex Press, 2009. http://www.lulu.com/content/paperback-book/the-cosmic-ring-dance-of-the-angels—softbound/7409216. (accessed September 21).

Isar, Nicoletta. “The dance of Adam: Reconstructing the Byzantine choros.” Byzantino-Slavica: Revue Internationale des Études Byzantines 61 (2003): 179-204.

Jessee, Dean C. 1969. “The earliest documented accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision.” In Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820-1844, edited by John W. Welch and Erick B. Carlson, 1-33. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2005.

Jones, Dan. 1847. History of the Latter-day Saints, from Their Establishment in the Year 1823, to the Time When Three Hundred Thousand of Them Were Exiled from America Because of Their Religion in the Year 1846. Translated by Ronald D. Dennis. Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2008.

Kimball, Stanley B. 1981. Heber C. Kimball: Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer. Illini Books ed. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1986. https://archive.org/details/PresidentHeberC.KimballsJournal. (accessed July 6, 2018).

Lundquist, John M. “What is reality?” In By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 428-38. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990.

———. The Temple: Meeting Place of Heaven and Earth. London, England: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

———. “Fundamentals of temple ideology from Eastern traditions.” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 651-701. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

———. The Temple of Jerusalem: Past, Present, and Future. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2008.

Lupieri, Edmondo. 1993. The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics. Italian Texts and Studies on Religion and Society, ed. Edmondo Lupieri. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2002.

Major, John S. Heaven and Earth in Early Han Thought: Chapters Three, Four, and Five of the Huainanzi. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993.

Malan, Solomon Caesar, ed. The Book of Adam and Eve: Also Called The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan: A Book of the Early Eastern Church. Translated from the Ethiopic, with Notes from the Kufale, Talmud, Midrashim, and Other Eastern Works. London, England: Williams and Norgate, 1882. Reprint, San Diego, CA: The Book Tree, 2005.

Martin, Richard C., ed. Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. 2 vols. New York, City, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, Gale Group, Thomson Learning, 2004.

McBride, Matthew. A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007.

Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2-3. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2007.

Morrow, Jeff. “Creation as temple-building and work as liturgy in Genesis 1-3.” Journal of the Orthodox Center for the Advancement of Biblical Studies (JOCABS) 2, no. 1 (2009). http://www.ocabs.org/journal/index.php/jocabs/article/viewFile/43/18. (accessed July 2, 2010).

Newby, Gordon Darnell. A Concise Encyclopedia of Islam. Oxford, England: Oneworld Publications, 2002.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1951. “The hierocentric state.” In The Ancient State, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 10, 99-147. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991.

———. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Parry, Jay A., and Donald W. Parry. “The temple in heaven: Its description and significance.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 515-32. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 1: Beresheis/Genesis. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1995.

Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions. Monographs of the Hebrew Union College 14. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992.

Sailhamer, John H. “Genesis.” In The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, edited by Frank E. Gaebelein, 1-284. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990.

Schaya, Léo. 1958. The Universal Meaning of the Kabbalah (L’homme et l’absolu selon la Kabbale). Translated by Nancy Pearson. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1974.

Seely, David Rolph, and Jo Ann H. Seely. “The crown of creation.” In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 11-23. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014.

Shelemon. ca. 1222. The Book of the Bee, the Syriac Text Edited from the Manuscripts in London, Oxford, and Munich with an English Translation. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. Reprint ed. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1886. Reprint, n. p., n. d.

Stordalen, Terje. Echoes of Eden: Genesis 2-3 and the Symbolism of the Eden Garden in Biblical Hebrew Literature. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2000.

Talmage, James E. 1912. The House of the Lord. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1998.

Townsend, John T., ed. Midrash Tanhuma. 3 vols. Jersey City, NJ: Ktav Publishing, 1989-2003.

Tvedtnes, John A. “Olive oil: Symbol of the Holy Ghost.” In The Allegory of the Olive Tree, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and John W. Welch, 427-59. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Vilnay, Zev. 1932. The Sacred Land. Legends of Jerusalem 1. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1973.

Weil, G., ed. 1846. The Bible, the Koran, and the Talmud or, Biblical Legends of the Mussulmans, Compiled from Arabic Sources, and Compared with Jewish Traditions, Translated from the German. New York City, NY: Harper and Brothers, 1863. Reprint, Kila, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. http://books.google.com/books?id=_jYMAAAAIAAJ. (accessed September 8).

Wenham, Gordon J. 1986. “Sanctuary symbolism in the Garden of Eden story.” In I Studied Inscriptions Before the Flood: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, edited by Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura. Sources for Biblical and Theological Study 4, 399-404. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1994.

Wheeler, Brannon M. Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Comparative Islam Studies, ed. Brannon M. Wheeler. London, England: Continuum, 2002.

Wintermute, O. S. “Jubilees.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 2, 35-142. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Wyatt, Nicolas. Space and Time in the Religious Life of the Near East. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Zlotowitz, Meir, and Nosson Scherman, eds. 1977. Bereishis/Genesis: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources 2nd ed. Two vols. ArtScroll Tanach Series, ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1986.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Bildarchiv, E 1546-C, with the assistance of Eva Farnberger.

Figure 2. Public Domain, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a6/Masjid-al-haram.jpg.

Figure 3. Illustration for Paradiso Canto 31, Divine Comedy (1308-1321) by Dante Alighieri. Public Domain, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d2/Paradiso_ Canto_31.jpg.

Figure 4. Public domain. Published in R. Giorgi, Anges, p. 63.

Figure 5. Image: 8 9/16 x 12 1/16 in. (21.7 x 30.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.220. Published in J. F. Dolkart, James Tissot, p. 206. With special thanks to Deborah Wythe and Ruth Janson.

Figure 6. © David Lindsley, , http://www.davidlindsley.com. With permission.

Figure 7. Photograph DSC03938, 3 January 2009, © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. With permission.

Figure 8. Figure © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Compare G. A. Anderson, Perfection, p. 80.

Figure 9. Figure © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

Footnotes

1 Rashi, Genesis Commentary, 1:25.

2 Moses 4:9. See U. Cassuto, Adam to Noah, p. 111. Many commentators have “solved” the problem by assuming that the account originally spoke of only one tree, and that the Tree of Life was a late addition to the text. For a brief survey on the question of one or two trees, and related textual irregularities, see T. N. D. Mettinger, Eden, pp. 5-11.

3 M. Zlotowitz et al., Bereishis, p. 96.

4 R. Guénon, Symboles, p. 325.

5 L. Ginzberg, Legends, 5:91 n. 50.

6 E.g., Wahb bin Munabbih in al-Tabari, Creation, 1:106, p. 277. See also A. Birrell, Mythology, p. 233; L. Ginzberg, Legends, 5:91 n. 50; J. C. Reeves, Jewish Lore, p. 96ff; J. A. Tvedtnes, Olive Oil, p. 430; B. M. Wheeler, Prophets, p. 23.

7 For a full and supportive analysis of this view, see T. N. D. Mettinger, Eden, especially pp. 34-41.

8 See H. W. Nibley, Hierocentric.

9 Ibid., p. 104. See Burrows, “Some Cosmological Patterns,” p. 46. Burrows further distinguishes “three cosmological patters corresponding to three ways of imagining the relation between heaven and earth. The first pattern is formed when the interest is at the center, on earth; the second when it is at the periphery, in heaven; the third may be considered a synthesis. … One might almost formulate a law that in the ancient East contemporary cosmological doctrine is registered in the structure and theory of the temples” (Burrows, “Some Cosmological Patterns,” p. 45).

10 Ibid., p. 110. For a survey of beliefs in the ancient Near East regarding the cosmic mountain at the center of the world, see N. Wyatt, Space, pp. 147–157.

11 See, e.g., J. M. Bradshaw, Tree of Knowledge,” 50–52; A. F. Ehat, Who Shall Ascend”; J. M. Lundquist, Reality; J. A. Parry et al., Temple in Heaven; T. Stordalen, Echoes, pp. 112-116, 308-309; T. D. Alexander, From Eden, pp. 20-23; G. K. Beale, Temple, 66–80; G. J. Wenham, Sanctuary Symbolism”; R. N. Holzapfel et al., Father’s House, 17–19; J. Morrow, Creation”; D. R. Seely et al., Crown of Creation.”

12 To see the relevance of this conception for the story of Enoch in the Book of Moses, see J. Bradshaw, Moses 6–7 and the Book of Giants.

13 Often symbolized as a cosmic tree, the temple also “originates in the underworld, stands on the earth as a ‘meeting place,’ and yet towers (architecturally) into the heavens and gives access to the heavens through its ritual” (J. M. Lundquist, Fundamentals, p. 675).

14 T. Stordalen, Echoes, pp. 288-289.

15 Isaiah 2:2.

16 Psalm 104:7-9.

17 J. M. Lundquist, Meeting Place, p. 7.

18 J. T. Townsend, Tanhuma, Qedoshim 7:10, Leviticus 19:23ff, Part 1, 2:309-310. See also J. M. Lundquist, Meeting Place, p. 7; J. M. Lundquist, Temple of Jerusalem, p. 26; Z. Vilnay, Sacred Land, pp. 5-6; O. S. Wintermute, Jubilees, 8:19, p. 73, 3:9-14, 27, pp. 59-60, 4:26, p. 63.

19 J. M. Lundquist, Fundamentals, pp. 666-671; cf. Matthew 6:10.

20 = Arabic “pilgrimage.” See R. C. Martin, Encyclopedia, 2:529-533; G. D. Newby, Encyclopedia, pp. 71-72.

21 = Arabic “cube.”

22 G. Weil, Legends, p. 83.

23 S. A. Ashraf, Inner, p. 125.

24 Greek empyros (fiery); derived from pyr (fire)—and not to be confused with the unrelated term “imperial.” See, e.g., R. Giorgi, Anges, pp. 63-65.

25 See M. Barker, Holy of Holies, p. 185.

26 1 Nephi 1:8.

27 H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, 17, p. 211. See also B. R. Bickmore, Restoring, pp. 304-306; N. Isar, Dance of Adam; F. M. Huchel, Cosmic (Book).

28 D. Blumenthal, Merkabah, p. 147.

29 E. Hennecke et al., NT Apocrypha, Acts of John, 94, p. 227.

30 Such symbolism illuminates the cosmology of the book of Abraham, where the planet Kolob is “set night unto the throne of God” (Abraham 3:9) with other planets in increasing distance from the center. The term Kolob “may derive from either of two Semitic roots with the consonants QLB/QRB. One has the meaning ‘to be near,’ as in Hebrew qarob (F. Brown et al., Lexicon, p. 898)… The other meaning is ‘center, midst,’ as in Hebrew qereb (ibid., p. 899)… In Arabic, qalb [heart, center] forms part of the names of several of the brightest stars in the sky, such as Antares… the constellation Scorpio… and Regulus… in the constellation Leo” (R. D. Draper et al., Commentary, pp. 289-290).

31 3 Nephi 11:8.

32 E.g., 2 Nephi 22:6; 3 Nephi 11:8, 21:17-18; cf. Isaiah 12:6; Jeremiah 14:9; Hosea 11:9; Joel 2:27; Micah 5:13-14; Moses 7:69; Zechariah 3:5, 15, 17. See S. K. Brown, Voices, pp. 150-151; R. D. Draper et al., Commentary, pp. 150-151.

33 3 Nephi 17:12, 13.

34 3 Nephi 17:12.

35 3 Nephi 17:24.

36 S. K. Brown, Voices, pp. 147-148.

37 Mathew 18:4.

38 3 Nephi 17:23.

39N. Wyatt, Space, p. 169. Recall also the description in Orson Pratt’s remembrance of Joseph Smith’s First Vision where, as the light drew nearer, “it increased in brightness, and magnitude, so that, by the time that it reached the tops of the trees, the whole wilderness, for some distance around, was illuminated in a most glorious and brilliant manner. He expected to have seen the leaves and boughs of the trees consumed, as soon as the light came in contact with them” (D. C. Jessee, First Vision, p. 21; cf. D. Jones, History, p. 15).

40 M. Zlotowitz et al., Bereishis, p. 101, cf. p. 96. See also L. Ginzberg, Legends, 1:70, 5:91 n. 50.

41 Ephrem the Syrian, Paradise, 3:5, p. 92. Note that the phrase “in the midst” was also used for the heavenly veil in the Creation account (Moses 2:6).

42 Brock in ibid., p. 52. Significantly, a Gnostic text describes the “color” of the Tree of Life as being “like the sun” while the “glory” of the Tree of Knowledge is said to be “like the moon” (H.-G. Bethge et al., Origin, 110:14, 20, p. 179.

43 E.g., G. A. Anderson et al., Synopsis, 19:1a-19:1d, pp. 56E-57E; G. Weil, Legends, p. 53; M. Herbert et al., Irish Apocrypha, p. 2 (“wall of red gold”). In at least one version of the story, Eve’s transgression of the boundary God had set in the midst of the Garden had been preceded by her deliberate opening of the gate to let the serpent enter the Garden’s outer wall (G. A. Anderson et al., Synopsis, 19:1a-19:1d, pp. 56E-57E).

44 E.g., M. Barker, Hidden, pp. 6-7; M. Barker, Christmas, pp. 85-86, 140. By way of contrast, most depictions of Jewish temple architecture show a menorah as being outside the veil. See J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 366-367 about the possibility that the story of the Garden of Eden included a “Tree of Life” on both sides of the veil.

Although the trees of Eden have been associated with the Garden Room of LDS temples since the time of Nauvoo (D. F. Colvin, Nauvoo Temple, p. 220; S. B. Kimball, Heber C. Kimball, p. 117; M. McBride, Nauvoo Temple, pp. 264-265), representations relating to the ultimate Tree of Life are centered on the Celestial Room. For example, the Celestial Room of the Salt Lake Temple is “richly embellished with clusters of fruits and flowers” (J. E. Talmage, House of the Lord (1998), p. 134). The Celestial Room of the Palmyra New York Temple features a large stained-glass window depicting a Tree of Life with “twelve bright multifaceted crystal fruits” (G. E. Hansen, Jr. et al., Sacred Walls, p. 4).

45 M. Barker, Older, p. 221, see pp. 221-232.

46 Revelation 22:1-3, G. A. Anderson et al., Synopsis, Greek 22:4, p. 62E. A late Christian text speaks of the “royal seat of the High-king in Paradise, in the very center of Paradise, moreover, where the Tree of Life was situated” (M. Herbert et al., Irish Apocrypha, p. 6).

47 G. B. Eden, Mystical Architecture, p. 22; cf. the idea of “the luxuriant sacred tree or grove… as a place of divine habitation” in D. E. Callender, Adam, p. 51; cf. pp. 42-54. See also T. Stordalen, Echoes, pp. 173, 293. Recall the book of Esther, which recounts the law of the Persians that “whosoever… shall come unto the king into the inner court, who is not called, [shall be] put… to death” (Esther 4:11). However, properly dressed in her royal apparel as a “true queen” instead of a “beauty queen” (see A. Berlin, Esther, pp. 51-52), Esther is—against all odds—granted safe admission to the presence of the king (Esther 5:1-2).

48 See Doctrine and Covenants 76:87, 112; Ephrem the Syrian, Paradise, 3:13-17, pp. 95-96.

49 B. C. Hafen, Broken, p. 30; cf. L. Schaya, Meaning, p. 16.

50 In ancient Israel and in the Kirtland Temple, the starting point for this movement was in the east, with the destination of most holiness being to the west. However, the Nauvoo and Salt Lake temples had their holiest places oriented to the east, where light would be greatest (V. Brinkerhoff, Day Star, 2:28, 30-31). The east doors of the Salt Lake Temple “are reserved for the Savior in his millennial return” (ibid., 2:30), however, in most modern temples, temple patrons enter through the door in a way that orients them “to the front of each of the initial ordinance rooms so that attention is focused on the concepts taught” (ibid., 2:31). “LDS temples constructed between 1890 and 1980 face all four points of the compass.” However, consistent with what seems to be an increased attention to temple symbolism, President Hinckley is remembered by one of the temple architects to have stated: “Where possible, movement in temples should be from east to west” (ibid., 2:30). For more on the direction of temple orientation and movement, see ibid., 2:27-31, 42-44.

51 R. O. Cowan, Dot, p. 174.

52 Moses 3:8. To an ancient reader in the Mesopotamian milieu, the phrase “eastward in Eden” could be taken as meaning that the garden sits at the dawn horizon—the meeting place of heaven and earth. The pseudepigraphal Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan skillfully paints such a picture: “On the third day, God planted the Garden in the east of the earth, on the border of the world eastward, beyond which, towards the sun-rising, one finds nothing but water, that encompasses the whole world, and reaches unto the borders of heaven” (S. C. Malan, Adam and Eve, 1:1, p. 1). This idea corresponds to the Egyptian akhet, the specific place where the sun god rose every morning and returned every evening, and also to the Mandaean “ideal world” which was held to hang “between heaven and earth” (E. S. Drower, Mandaeans, p. 56; E. Lupieri, Mandaeans, p. 128). The Chinese K’un-lun also “appears as a place not located on the earth, but poised between heaven and earth” (J. S. Major, Heaven, p. 156). The gardens of Gilgamesh and the Ugaritic Baal and Mot were liminally located at the “edges of the world” or, in other words, “at the borders between the divine and the human world” (T. Stordalen, Echoes, pp. 285-286). Similarly, 2 Enoch locates paradise “between the corruptible [earth] and the incorruptible [heaven]” (F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch, 8:5, p. 116; cf. p. 116 n. l).

By its very nature, the horizon is not a final end point, but rather a portal, a place of two-way transition between the heavens and the earth. Writes Nibley: “‘Egyptians… never… speak of [the land beyond the grave] as an earthly paradise; it is only to be reached by the dead.’ … [It] is neither heaven nor earth but lies between them… In a Hebrew Enoch apocryphon, the Lord, in visiting the earth, rests in the Garden of Eden and, moving in the reverse direction, passes through ‘the Garden to the firmament’ (See P. Alexander, 3 Enoch, 5:5, p. 260)… Every transition must be provided with such a setting, not only from here to heaven, but in the reverse direction in the beginning” (H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), pp. 294-295. See also H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, 16, pp. 198-199). “The passage from world to world and from horizon to horizon is dramatized in the ordinances of the temple, which itself is called the horizon” (Siegfried Schott, cited in ibid., 16, p. 199). Situating this concept with respect to the story of Adam and Eve, the idea is that the Garden “was placed between heaven and earth, below the firmament [i.e., the celestial world] and above the earth [i.e., the telestial world], and that God placed it there… so that, if [Adam] kept [God’s] commands He might lift him up to heaven, but if he transgressed them, He might cast him down to this earth” (Shelemon, Book of the Bee, 15, p. 20).

Eastward orientation is not only associated with the rising sun, but also with its passage from east to west as a metaphor for time (N. Wyatt, Space, pp. 35-52; cf. B. N. Fisk, Remember, 1:7, p. 5). The Hebrew phrase mi-kedem (‘in the east’) in the Genesis account could also be translated “in the beginning” or “in primeval times” (T. Stordalen, Echoes, pp. 261-270; cf. Habakkuk 1:12). Likewise, for the Egyptians, the West, the direction of sunset, was the land of the dead—hence the many tombs built on the west bank of the Nile.

53 J. H. Sailhamer, Genesis, pp. 41-42; T. Stordalen, Echoes, pp. 267-268.

54 The phrase “in the cool of the day” in Moses 4:14 can be translated as “in the wind, breeze, spirit, or direction” of the day—in other words, the voice is coming from the west, the place where the sun sinks (M. Zlotowitz et al., Bereishis, pp. 122-123). Since the voice is coming from the west, some commentators infer that Adam and Eve were then located on the east side—the end of the Garden furthest removed from the presence of the Lord—and possibly related to what Islamic commentary calls “the courtyard” (e.g., A. a.-S. M. H. at-Tabataba’i, Al-Mizan, 1:209). In other words, they seem to have one foot outside the Garden already (see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 261, 280). Thus, God’s question to Adam in the Genesis account—“Where art thou?”—might be taken as deeply ironic. In the view of Didymus, it is really not a question but rather “a statement of judgment as to what Adam has lost” (cited in G. A. Anderson, Perfection, pp. 215-216). The idea of Adam and Eve being in the “courtyard” of Eden is an appropriate fit to the function of the outermost of the three divisions of the Israelite temple, a place of confession as the first step of reconciliation (J. L. Carroll, Reconciliation, pp. 96-99).

55 Moses4:31.

56 Moses 5:41.

57 Genesis 11:2.

58 Genesis 13:11.

59 J. H. Sailhamer, Genesis, p. 59 and Genesis 14:17-20.

60 T. L. Brodie, Dialogue, p. 117.

61 Matthew 2:1. See J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 673-674.

62 Malachi 3:1.

63 Joseph Smith-Matthew 1:26.

64 Alma 12:30.

65 Alma 12:37.