Book of Moses Essay #14

Moses 6:51–68

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and Matthew L. Bowen

Enoch Teaches the Plan of Salvation

In reviewing ancient and modern threads that highlight Enoch’s roles as a missionary, prophet, and visionary, we must not overlook his effectiveness as a teacher. Among the most precious and significant insights he conveyed to the people is the sequence described in Moses 6:60, whereby all people may be “born again into the kingdom of heaven”1:

For by the water ye keep the commandment; by the Spirit ye are justified, and by the blood ye are sanctified.

Hugh Nibley described Moses 6:51–68 as an “excerpt from the Book of Adam.”2 Genesis 5:1 mentions “the book of the generations of Adam” as a source document for the material recorded in that chapter. Moses 6:8 characterizes the “book of the generations of Adam” as “a genealogy” that “was kept of the children of God”—i.e., a record of those who had been “born again into the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven” (v. 59) or those who had received the ordinances set forth for that purpose.

Thus, Moses 6:51–68 may have formed part of the “book of remembrance” mentioned in Moses 6:46, a record similar in function to the “book of remembrance” written for those who would become the Lord’s sĕgullâ—his “jewels” or “special possession” (NRSV); or, rather, his specially marked or “sealed” possession—mentioned in Malachi 3:16. Its function as a record of genealogy and ordinances may have been like the “book containing the records of our dead, which shall be worthy of all acceptation” envisioned by Joseph Smith in Doctrine and Covenants 128:2,3 a verse which quotes Malachi 3:2–3. Note that the Holy Spirit of Promise is the “sealer” and the “record of heaven,”4 as further described below.

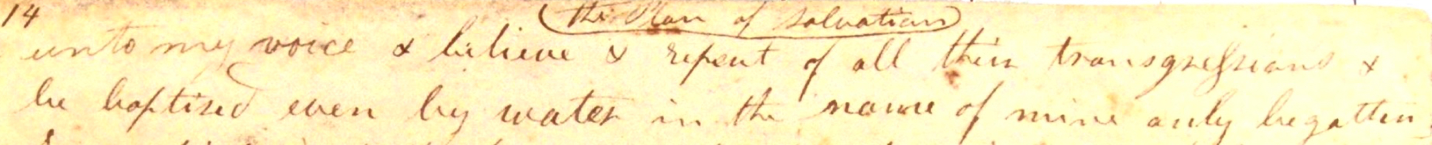

The setting for Moses 6:51–68 is a sermon by Enoch. A notation in the handwriting of John Whitmer on the OT1 manuscript above Moses 6:52b reads “The Plan of Salvation.”5 The verses that follow were sometimes cited by early leaders of the Church as evidence for the continuity of the plan of salvation from the time of Adam and Eve to our day.6

The Meaning of the Name Enoch

Significantly, Enoch (Henoch or Hanoch, Heb. ḥănôk) sounds identical to the Hebrew passive participle of the verbal root ḥnk, “train up” “dedicate.”7 Thus, for a Hebrew speaker, the name ḥănôk/Enoch would evoke “trained up” or “initiated” — bringing to mind not only the general role of a teacher, but also the idea of someone who was familiar with the temple and could train and initiate others as a hierophant. Before it became the name of the post-Mosaic Feast of Dedication, the Hebrew noun ḥănukkâ had reference to the “consecration” or “dedication” of the temple altar,8 including the sacred dedication of the altar for Solomon’s temple.9

Strengthening the connection of Enoch’s name to the temple, we note that in Egyptian, the ḥnk verbal root denotes to “present s[ome]one” with something, to “offer s[ome]thing” or, without a direct object, to “make an offering.”10 The Egyptian nouns ḥnk and ḥnkt denote “offerings.”11 In other words, it is a cultic term with reference to cultic offerings.

Thus, when we read Moses 6:21: “And Jared taught Enoch in all the ways of God,” we should not take this as merely a general statement that Enoch knew something about religious matters, but specifically that he was familiar with temple rites and what we would today call “the doctrine of Christ.”12 This theme is reiterated in Moses 6:57–58:

Wherefore teach it unto your children, that all men, everywhere, must repent, or they can in nowise inherit the kingdom of God, for no unclean thing can dwell there, or dwell in his presence; for, in the language of Adam, Man of Holiness is his name, and the name of his Only Begotten is the Son of Man, even Jesus Christ, a righteous Judge, who shall come in the meridian of time. Therefore I give unto you a commandment, to teach these things freely unto your children …

This gospel “teaching” is a key theme of Moses 6–7.13

Going further, a form of the verb ḥnk (nearly homonymous with ḥănôk/Enoch) is the key term in Proverbs 22:6: “Train up [ḥănōk] a child in the way [i.e., the temple, the doctrine of Christ] he should go: and when he is old, he will not depart from it.” Indeed, Lehi appears to recite this very proverb when he says to the children of Laman and Lemuel: “But behold, my sons and my daughters, I cannot go down to my grave save I should leave a blessing upon you; for behold, I know that if ye are brought up [i.e., ḥnk] in the way [i.e., the doctrine of Christ, the temple; cf. 2 Nephi 31–32] ye should go ye will not depart from it.”14

Enoch initially describes himself as an uninitiated “lad” lacking power of speech: “Why is it that I have found favor in thy sight, and am but a lad, and all the people hate me; for I am slow of speech; wherefore am I thy servant?”15 David, early in his career, is similarly described as an ʿelem (“young man,” “youth,” “lad,” pausal ʿālem) in 1 Samuel 17:56 and Jonathan’s servant is described synonymously as both a naʿar (“young man,” “lad”) and an ʿelem in 1 Samuel 20:22. One of the etymological associations suggested for ʿelem is that it “is related to the root of [ʿwlm], “unknowing, uninitiated.”16 In Arabic ʿlm is the primary verb for “to know.” Alma the Elder, whose name derives from ʿelem, is introduced into the Book of Mormon as a “young man” who “believed the words of Abinadi” (Mosiah 17:2)17 and then taught those words18 on his way to becoming the founder of what became the Nephite church and a religious movement. The aforementioned biographical description of Alma harks back to Nephi’s autobiography: “I, Nephi [nfr > nfi =good], having been born of goodly parents, therefore I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father … yea, having had a great knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of God,”; “I, Nephi, being exceedingly young, nevertheless being large in stature, and also having great desires to know of the mysteries of God, wherefore, I did cry unto the Lord; and behold he did visit me, and did soften my heart that I did believe all the words which had been spoken by my father.”19 Part of Enoch’s transformation into the powerful speaker and teacher par excellence involved moving beyond one who had been “taught in all the ways of God” to one who taught all the ways of God—the doctrine of Christ—and “walked with God,”20 including walking in His ways.

The theme of the doctrine of Christ brings us to the essential role of the saving ordinances, including not only baptism and the gift of the Holy Ghost but also the essential ordinances of the temple.21 Hugh Nibley cited the Enoch scholar André Caquot as saying that Enoch is:22

“in the center of a study of matters dealing with initiation in the literature of Israel.”23 Enoch is the great initiate who becomes the great initiator.24 … The Hebrew book of Enoch bore the title of Hekhalot, referring to the various chambers or stages of initiation in the temple.25 Enoch, having reached the final stage, becomes the Metatron to initiate and guide others.26 “I will not say but what Enoch had Temples and officiated therein,” said Brigham Young, “but we have no account of it.”27 Today we do have such accounts.

The Structure of Moses 6:51–68

The scripture passage that summarizes Enoch’s teaching is elegantly laid out. Verses 51–68 form a beautiful formal structure of several parts that is outlined in provisional form in the Appendix. The passage epitomizes the saving ordinances, highlighting the symbolism of water, the Spirit, and the blood of Jesus Christ as the means of sanctification. After a summary description of God’s culminating promise to the sanctified, Adam obediently hearkens to all these commandments and receives the blessings associated with that promise, becoming a son of God.

In verse 51, the Father opens the passage by appealing to His role as the Creator, a theme that is characteristic of the record of Enoch’s ministry. Outside the chapters that describe Creation itself, there appears to be no more significant clustering of verses in scripture referring to the specific theme of God as the author of all things than we have in Moses 6.28 Naturally, the theme of Creation is foundational to the story of the Fall and the Atonement that will be summarized later in the passage. However, in addition, Benjamin McGuire observes that this verse serves “as a motive clause of the sort we might anticipate from an Old Testament text.”29 Since God “has called man and the universe into being, man owes Him obedience and is subject to His commandments,” including the commandments to hearken, to believe, to repent, and to be baptized that are outlined in verse 52.

The passage proper opens in verse 52. The verse is a firsthand statement from God wherein He, as the Maker of the world and of men (see verse 51), summarizes the commandments underlying the plan of salvation one by one — namely, to hearken (A), believe (B), repent (C), and be baptized (D). Then, in verses 53–60, He motivates the first three commandments one by one in reverse order (i.e., D’, C’, B’) within what seems to be a succession of ladder-like rhetorical cascades that culminate in a promise of sanctification through “the blood of [His] Only Begotten.”30

Verse 61 is an explanation of that culminating promise. It must be understood that the sure knowledge provided by the “record of heaven”31 that is promised to Adam and Eve and their posterity in verse 61 is more than the prefatory witness that comes to those who have “receive[d] the Holy Ghost.”32 Rather, as we describe in more detail in other Essays,33 this knowledge is associated with the sealing power.

Verses 62–63 also seem to constitute an explanation, reiterating the central role of Jesus Christ in the plan of salvation and testifying that all things bear record of Him.

Verses 64–65 recount how, in response to God’s explanation of the “plan of salvation,” Adam hearkened (A’) without hesitation to the voice of the Father by obeying the commandments he had just been given (i.e., B, C, D).34 Once having demonstrated his faithfulness in all things, Adam also received the promised “record of heaven”35 described in verse 66 more specifically as the “record of the Father, and the Son” that declared his election sure through “a voice out of heaven.”36 Having had “all things confirmed unto [him] by an holy ordinance,”37 Adam had been “born again into the kingdom of heaven of water, and of the Spirit, and … cleansed by blood,” thus having become a “son of God”38 in the full sense of the term.39

In subsequent Essays we will discuss the title “Son of Man” in the Bible and in 1 Enoch’s Book of Parables. Then we will explore the signification of the Father’s succinct description of the plan of salvation in Moses 6:60 as taught by Enoch, whose name, both in ancient and modern times, is invariably associated with the earthly and heavenly temple:

For by the water ye keep the commandment; by the Spirit ye are justified, and by the blood ye are sanctified.

This article is adapted from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. “Truth and Baauty in the Book of Moses.” In Proceedings of the Fourth Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 10 November 2018, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple on Mount Zion 5, in preparation. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 75-85.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. “Truth and Beauty in the Book of Moses.” In Proceedings of the Fourth Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 10 November 2018, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple on Mount Zion 5, in preparation. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books.

Christofferson, D. Todd. “Born again.” Ensign 38, May 2008, 76-79.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 101-106.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, pp. 144-154.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, pp. 277-281.

Appendix: A Provisional Proposal for Structuring Moses 6:51–58

We suggest the following provisional proposal for structuring Moses 6:51–58:

1. Motive clause, appealing to God’s role as the Creator to justify His commandments

2. Résumé of the commandments to hearken (A), believe (B), repent (C), and be baptized (D) (vv. 51–52). Then, in reverse order of these commandments:

a. Why one must be baptized (D’, vv. 53–54)

b. Why one must repent in preparation for baptism (C’, vv. 55–57)

c. What one must believe and understand in order to awaken a desire for repentance (B’, vv. 58–60)

d. Explanation of the culminating promise made to the sanctified: They shall receive the “record of heaven,” being thus sealed up to eternal life (v. 61)

3. Explanation of the central role of the Only Begotten:

a. The “plan of salvation” comes through the blood of the Only Begotten (v. 62)

b. All things bear record of the Only Begotten (v. 63)

4. Adam hearkens (A’) to the voice of the Lord by obeying the commandments outlined above (i.e., B, C, D) (vv. 64–66)

5. Adam then receives the promised “record of the Father, and the Son” wherein the Father declares the sonship of Adam.40 The Father then adds: “Thus may all become my sons” (vv. 66–68). In other words, thus may all be made “kings and priests unto God.”41

The structure proposed above is applied to the verses in full below. The text below generally follows the OT1 manuscript as originally dictated, with spelling, grammar, and punctuation modernized. Exceptions and notable differences in subsequent editions are shown in square brackets and described in the endnotes. Italicized text within brackets indicates phrases added to clarify implicit parallels. Different colors indicate different speakers: blue for God, green for Enoch, and black for the narrator. We are grateful to Noel Reynolds for sharing his expertise in structuring scripture, though any resulting faults are ours.

References

Alexander, Philip S. “3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

———. “From son of Adam to second God: Transformations of the biblical Enoch.” In Biblical Figures Outside the Bible, edited by Michael E. Stone and Theodore A. Bergren, 87-122. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1998.

Andrus, Hyrum L. Doctrinal Commentary on the Pearl of Great Price. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1970.

Bowen, Matthew L. “Alma — Young man, hidden prophet.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 19 (22 April 2016): 343-53. http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/alma-young-man-hidden-prophet/. (accessed 28 August 2016).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. www.templethemes.net.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent.” In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017. www.templethemes.net.

Caquot, André. “Pour une étude de l’initiation dans l’ancien Israel.” In Initiation, edited by C. Bleeker, 119-33. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1965.

Faulkner, Raymond O. 1962. A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. Oxford, England: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, 1991. https://community.dur.ac.uk/penelope.wilson/Hieroglyphs/Faulkner-A-Concise-Dictionary-of-Middle-Egyptian-1991.pdf. (accessed March 18, 2020).

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Faulring, Scott H., and Kent P. Jackson, eds. Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible Electronic Library (JSTEL) CD-ROM. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University. Religious Studies Center, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2011.

Halivni, David Weis. Midrash, Mishnah, and Gemara: The Jewish Predilection for Justified Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986.

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/book-moses-and-joseph-smith-translation-manuscripts. (accessed August 26, 2016).

Koehler, Ludwig, Walter Baumgartner, Johann Jakob Stamm, M. E. J. Richardson, G. J. Jongeling-Vos, and L. J. de Regt. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. 4 vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1994.

McGuire, Benjamin L. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, May 15, 2013.

Mopsik, Charles, ed. Le Livre Hébreu d’Hénoch ou Livre des Palais. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1989.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Pratt, Orson. 1873. “The ancient gospel; Adam’s transgression, and man’s redemption from its penalty, etc. (A sermon by Elder Orson Pratt, delivered in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, September 11, 1859).” In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 7, 251-66. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Reeves, John C. “Some explorations of the intertwining of Bible and Qur’an.” In Bible and Qur’an: Essays in Scriptural Intertextuality, edited by John C. Reeves. Symposium Series 24, 43-60. Leiden, The Netherlands: Society of Biblical LIterature and Brill, 2004. https://books.google.com/books?id=WNId86Eu4TEC. (accessed May 12, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Young, Brigham. 1877. “The great privilege of having a temple completed; past efforts for this purpose; remarks on conduct; earth, heaven, and hell, looking at the Latter-day Saints; running after holes in the ground; arrangements for the future (Remarks by President Brigham Young, delivered at the temple, St. George, January 1, 1877).” In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 18, 303-05. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1884. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 75-85.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. “Beauty and Truth in the Book of Moses: Enoch Unfolds the Plan of Salvation.” In Proceedings of the Fourth Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 10 November 2018, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple on Mount Zion 5, in preparation. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books.

Christofferson, D. Todd. “Born again.” Ensign 38, May 2008, 76-79.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 101-106.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, pp. 144-154.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, pp. 277-281.

Notes for Figures

Figure 1. Image from S. H. Faulring et al., JST Electronic Library.

Footnotes

1 Moses 6:59.

2 H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, p. 277.

3 Joseph Smith also quoted Revelation 20:12 which describes the judgment of the dead out of “books” that were written “according to their works” (see D&C 128:6–7).

4 Moses 6:61.

5 S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, OT1 (p. 14 [Moses 6:52–64]), p. 101. See J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, Commentary Moses 6:51-a, p. 75. See also Moses 6:62.

6 See, for example, O. Pratt, 11 September 1859, pp. 251–253.

7 L. Koehler et al., Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon, 1:334.

8 Numbers 7:10–11, 84, 88.

9 See 2 Chronicles 7:9.

10 R. O. Faulkner, Concise Dictionary, p. 173.

11 Ibid., p. 173.

12 Hebrews 6:1; 2 John 1:9; 2 Nephi 31:2; 32:6; Jacob 7:2, 6; 3 Nephi 2:2. For a discussion of the temple-related ideas implicit in scriptural usages of this term, see J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, pp. 78–111.

13 In Islam, Enoch is called Idrīs. The ninth-century Muslim scholar Ibn Qutayba attributed this name to Enoch “on account of the quantity of knowledge and religious practices which he learned [darasa] from the scripture of God” (J. C. Reeves, Some Explorations, p. 48). Thus (ibid., p. 49):

the name Idrīs reflects a wordplay on the verbal root darasa, which is in turn connected with the acquisition and promulgation of knowledge. Enoch becomes Idrīs to mark that character’s distinction in academic pursuits. Unsurprisingly, this is precisely the type of curriculum vita exhibited by the character Enoch within Jewish and Christian pseudepigraphal sources: he is the first to write, he becomes proficient in astronomical and calendrical lore, and he admonishes his contemporaries — the infamous dōr ha-mabbūl — to practice righteousness and true piety. These same collections of traditions often supply a series of reasons why Enoch deserved this boon, most of which revolve around his scholastic attainments and exemplary piety. Given his scholastic and moral attenments, and the well-attested intercultural popularity of the figure of Enoch as celestial voyager and purveyor of supernatural secrets, it should occasion little surprise that the Qur’ān and its early exegetes likewise signal a familiarity with these influential literary traditions.

14 2 Nephi 4:5.

15 Moses 6:31.

16 L. Koehler et al., Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon, 1:835. Citing Gerleman ZAW 91 (1979): 338–349.

17 M. L. Bowen, Alma.

18 Mosiah 18:1, 3.

19 1 Nephi 2:16.

20 Moses 6:34, 39; 7:69.

21 See J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, pp. 78–111.

22 H. W. Nibley, Enoch, pp. 19–20.

23 A. Caquot, Pour une Étude, p. 121: “au centre d’une étude des thèmes initiatiques dans la littérature israélite : son nom se rattache à la racine … qui signifie en hébreu, ‘inaugurer’ ou ‘consacrer.’”

24 See ibid., p. 121.

25 See P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch; C. Mopsik, Hénoch.

26 According to Philip Alexander (P. S. Alexander, From Son of Adam, p. 107 n. 31):

One very plausible etymology derives [the title Metatron] from the Latin metator [Greek mitator]. … The metator was the officer in the Roman army who went ahead of the column on the march to mark out the campsite where the troops would bivouac for the night. Hence, figuratively, ‘forerunner’” (see P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch, p. 228).

Alexander further concludes that Metatron was “first incarnate in Adam and then reincarnate in Enoch” (P. S. Alexander, From Son of Adam, p. 111).

27 B. Young, 1 January 1877, p. 303.

28 Moses 6:33, 44, 51, 59, 63; 7:32–33, 36, 59, 64.

29 Benjamin McGuire comments (B. L. McGuire, May 15 2013):

This whole concept of “God … made you” (Moses 6:33) is one of the two general sorts of motive clauses used to justify commandments in the Old Testament (the other is, “I brought you out of Egypt”). In other words, consistently in the Old Testament, one of the reasons given for the people needing to obey the commandments is that God created them (and the world in general). For example, Havlini writes (D. W. Halivni, Midrash, pp. 11, 12–13):

But along with the individual motives there are also expressly general motives, serving as an overall justification for God to issue commandments. That right is granted Him by virtue of His being the creator of the universe, with a special claim on, the Israelites because He led them out of Egypt.

God as creator makes an even stronger claim: since He has called man and the universe into being, man owes Him obedience and is subject to His commandments. In His capacity as the creator, God could have imposed laws on any nation; but He chose to exercise His sovereignty over Abraham’s children because of the covenant He entered into with them. He singled them out by miraculously taking them out of slavery, freeing them from bondage.

Thus the two principal general motives, God as the creator (the beginning of the world) and God as the redeemer (the beginning of the national Jewish history), act as one.

Within this context, “God … made you” is clearly a motive clause of the sort we might anticipate from an Old Testament text in, e.g., Deuteronomy 32:6 or Isaiah 44:2: “Thus saith the Lord that made thee, and formed thee from the womb.”

30 Moses 6:62.

31 Moses 6:61.

32 Acts 8:15, 19; 2 Nephi 31:13; 32:5; 3 Nephi 28:18; 4 Nephi 1:1; D&C 25:8; 84:74; Moses 8:24.

33 See Book of Moses Essays #21 and #22, forthcoming.

34 Moses 6:64–65.

35 Moses 6:61.

36 Moses 6:66.

37 Moses 5:59.

38 Moses 6:68.

39 See Book of Moses Essay #21, forthcoming.

40 Cf., e.g., 3 Nephi 31:20: “thus saith the Father: Ye shall have eternal life.”

41 Revelation 1:6.

42 “in the flesh” did not appear in OT1, but was added in OT2 (K. P. Jackson, Book of Moses, s.v. OT2 Page 17 [Moses 6:40–53]).

43 OT1 reads “their transgressions.” A change to “thy transgressions” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 17 [Moses 6:40–53]).

44 OT1 reads “by water.” A change to “in water” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 17 [Moses 6:40–53]).

45 OT1 reads “which is full.” A change to “who is full” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 17 [Moses 6:40–53]).

46 See John 1:14; Alma 5:48; D&C 84:102; 93:11.

47 See Acts 4:12; 2 Nephi 25:20; 31:21; Mosiah 3:17; 5:8; D&C 18:23.

48 See Matthew 21:22; John 14:13; 15:16; 16:23; 1 John 5:13–15; Enos 1:15; Mosiah 4:21; 3 Nephi 18:20; 27:28; Moroni 7:26; D&C 29:6; D&C 50:29; 88:64. OT1 reads “& ye shall ask all things in his name & what ye shall ask it shall be giv[en]” A change to “and ye shall ask all things in his name, and whatsoever ye shall ask it shall be given ” was made in OT2 (K. P. Jackson, Book of Moses, s.v. OT2 Page 17 (Moses 6:40–53)). Though the OT2 addition correctly anticipates the gift of the Holy Ghost given after baptism, it seems to interrupt the flow of the overall passage, whose subject is Jesus Christ.

49 OT1 reads “by water.” A change to “in water” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 17 [Moses 6:40–53]).

50 OT1 reads “transgressions.” A change to “transgression” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 18 [Moses 6:53–63]).

51 OT1 reads “Christ.” A change to “the son of God” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 18 [Moses 6:53–63]).

52 H. L. Andrus, Doctrinal, pp. 247–248 comments on this phrase as follows:

Children are conceived on earth in sin. Thus all the effects of the fall were not abolished by the power of the atonement. The purpose of Adam’s transgression was to institute a fallen, probationary state in which man could be tested and proven in the new physical endowments of life he would receive on earth, and where he could learn to walk by faith in reliance upon God. To this end, certain corrupt elements became associated with the flesh as a result of the fall and the subsequent transgressions of man. “Because of the fall,” the brother of Jared therefore said in apology to the Lord, “our natures have become evil continually.” The corruption, or evil, in the flesh gives “the spirit of the devil power to captivate” and to bring man down to hell, if he yields to the desires of the flesh and the enticements of the Adversary. These elements of corruption and forces of sin are implanted in the flesh at conception, and for this reason the scripture states that man is conceived in sin. Man’s mortal body is organized in weakness as a corrupt body, whereas his resurrected body is organized in power as a spiritual body. Of the purpose of mortal weaknesses, the Lord said to Moroni (Ether 12:27):

if men come unto me I will show unto them their weakness. I give unto men weakness that they may be humble; and my grace is sufficient for all men that humble themselves before me; for if they humble themselves before me, and have faith in me, then will I make weak things become strong unto them.

53 “another law and commandment.” We take this to mean that, in addition to D, the previously given law and commandment to be baptized, the Lord is now giving C, the law and commandment to repent.

54 OT1 reads “which shall com[e come.” A change to “which shall come ” was made in OT2 (K. P. Jackson, Book of Moses, s.v. OT2 Page 18 [Moses 6:53–63]). We have included the phrase “in the meridian of time,” which is attested in OT1 in verse 62.

55 “I give unto you a commandment,” which we take to be referring back (implicitly) to B, the commandment to believe. “Therefore” was added in OT2 (K. P. Jackson, Book of Moses, s.v. OT2 Page 18 [Moses 6:53–63]).

56 The italicized words were included in OT1 but were moved, modified, and truncated (e.g., leaving out “the mysteries of”) in OT2. OT2 reads: “ I give unto you a commandment to teach these things freely unto your Children Saying that in as much as they were born into the World by the fall which bringeth death by water and blood and the Spirit which I have made and so became of dust a living soul even so ye must be born again of water and the spirit and cleansed by blood even the blood of mine only begotten into the mysteries of the kingdom of Heaven <Therefore, I give unto you a commandment, to teach these things freely unto your children, saying, that by reason of transgression cometh the fall, which fall bringeth death, And in as much as they were born into the world by water, and blood, and the spirit which I have made, and so became of dust a living soul; even so ye must be born again, into the kingdom of heaven, of water, and of the Spirit, and be cleansed by blood, even the blood of mine only begotten.>” (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 18 (Moses 6:53–63)). The OT2 version rather than the OT1 version is used in the 2013 edition of Moses 5:59.

57 OT1 reads “that in you is given the record of Heaven.” The change to “that in you is given the record of Heaven” was made in OT2 (ibid., s.v. OT2 Page 18 (Moses 6:53–63)).

58 Cf. Moses 6:66.

59 A change was made in OT2 in the handwriting of Sidney Rigdon as a replacement for OT1’s “the Peac[i]ble things of immortal grory” [glory] (S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, OT1 (p. 14), p. 102. Cf. D&C 36:2; 39:6; 42:61). Significantly, OT2 reads: “the peaceable things of immortal glory “ (K. P. Jackson, Book of Moses, s.v. OT2 Page 18 (Moses 6:53–63)). Note that D&C 42:61 links the “peaceable things” with “the mysteries” as the results of revelation:

If thou shalt ask, thou shalt receive revelation upon revelation, knowledge upon knowledge, that thou mayest know the mysteries and peaceable things—that which bringeth joy, that which bringeth life eternal.

Following a decision by the RLDS publication committee in the preparation of their 1867 publication of the “Inspired Version,” Moses 6:61 uses the OT1 version rather than the OT2 version.

60 “through” was added in OT2 (K. P. Jackson, Book of Moses, s.v. OT2 Page 18 [Moses 6:53–63], p. 614).

61 OT1 and OT2 read “which.” This was changed to “who” in the preparation of the manuscript of the RLDS “Inspired Version” for publication.

62 H. L. Andrus, Doctrinal, pp. 257–258:

There are several symbolic elements in this statement by Paul. In baptism, man is buried with Christ into death, the “old man” being crucified with Christ. When the body is beneath the water, it is symbolic of Christ’s body in the tomb. As Christ was raised up by the glory of the Father, filled with a fulness of the Father’s divine nature, so should man come forth from the liquid tomb to a “newness of life,” being filled with the divine powers that are given in the new birth to abide in him. Finally, in baptism man is like a seed that must be planted in order to spring forth into a new life. God’s promise is that those who are planted together in the likeness of Christ’s death will be also in the likeness of His resurrection. The new life they will come forth to possess in the resurrection is eternal life, or the kind of glorified life that Christ possesses. Joseph Smith explained (J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 20 March 1842, pp. 197–198. Original source: JS, Discourse, Nauvoo, IL, 20 March 1842, Wilford Woodruff, Diary, pp. 134-138 [p. 136]; handwriting of Wilford Woodruff; CHL, posted as interim content on The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/discourse-20-march-1842-as-reported-by-wilford-woodruff/3 [accessed January 23, 2020]):

God has set many signs on the earth, as well as in the heavens; for instance, the oak of the forest, the fruit of the tree, the herb of the field, all bear a sign that seed hath been planted there; for it is a decree of the Lord that every tree, plant, and herb bearing seed should bring forth of its kind, and cannot come forth after any other law or principle. Upon the same principle do I contend that baptism is a sign ordained of God, for the believer in Christ to take upon himself in order to enter into the kingdom of God, “for except ye are born of water and of the Spirit ye cannot enter into the Kingdom of God,” said the Savior. It is a sign and a commandment which God has set for man to enter into His kingdom. Those who seek to enter in any other way will seek in vain; for God will not receive them, neither will the angels acknowledge their works as accepted, for they have not obeyed the ordinances, nor attended to the signs which God ordained for the salvation of man, to prepare him for, and give him a title to, a celestial glory.

63 We take Adam’s full-hearted response, epitomized in his cry unto the Lord, as an indicator of his desire to obediently “hearken” (A) to the Lord’s commandments. Admittedly, since the term “hearken” or its equivalent does not explicitly appear in this passage, it is the weakest of the parallelisms to the list of commandments given in Moses 6:52.

64 We take this to be an interpolation of the narrator, explaining that Moses 6:67 refers to the “record of heaven” that was mentioned in Moses 6:61.

65 I.e., after the order of Jesus Christ, who was “made an high priest for ever after the order of Melchisedec” (Hebrews 6:20. Cf. Psalm 110:4). Adam is thus made a priest “unto God” (see Revelation 1:6).

66 Cf. Psalm 2:7. Adam is thus made a king “unto God” (see Revelation 1:6).