Book of Moses Essay #48

Moses 2:5

With contribution by Matthew L. Bowen and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

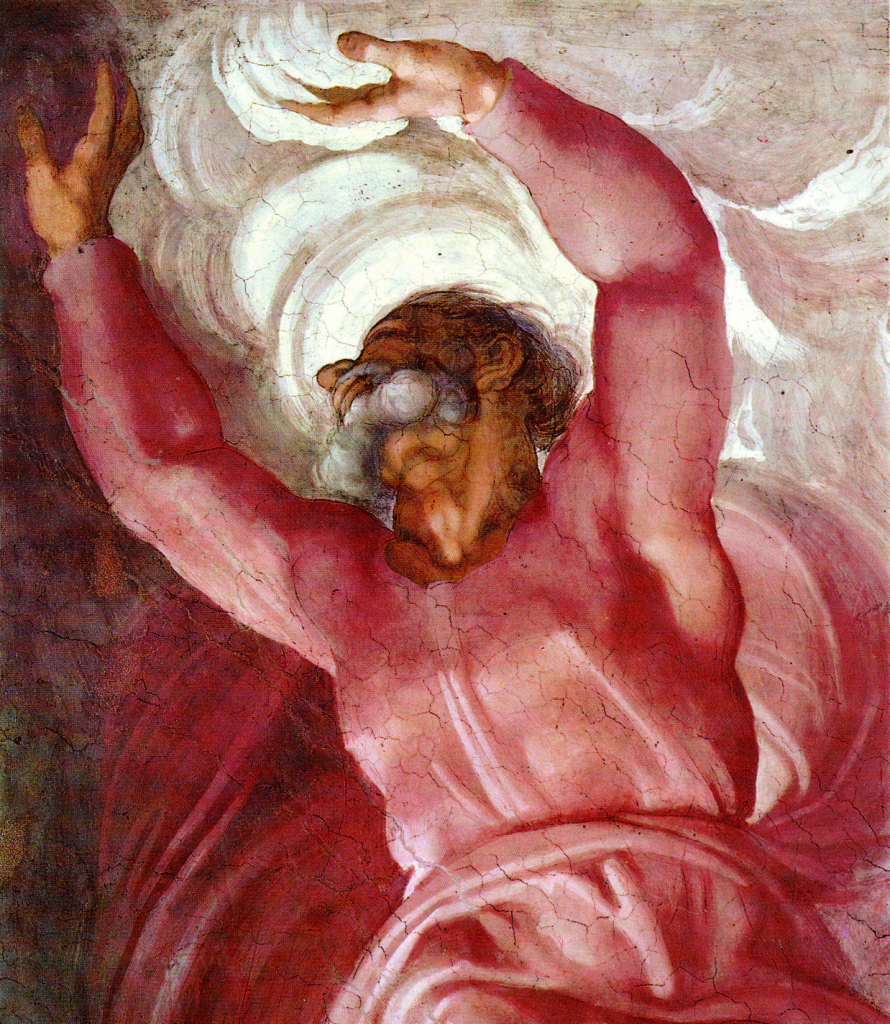

Distinction and separation are the central themes of the creation account:1 “And I, God, said: Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven, to divide the day from the night” (Moses 2:14). In Michelangelo’s masterful depiction, God dramatically extends his arms in opposite directions, majestically assigning the golden ball of the sun to rule the day, and the gray moon to rule the night. To achieve a “special otherworldly effect,” the moon was “painted without paint”—in other words, it is the actual color of the bare plaster surface beneath the fresco itself.2

Although, from a Latter-day Saint perspective, it is hard to imagine a more “traditional” depiction of creation, Michelangelo’s portrait is thoroughly unacceptable to rabbinic Judaism. For one thing, Ellis observes, the anthropomorphic portrayal violates both the second commandment and also the idea that God is “unknowable, unimaginable” and “visually unportrayable.” Additionally, God is shown as effecting creation through action rather than by the sole means of “potent speech-acts that enact the creative power of language.” Thus, he explains, Michelangelo’s God is both inexplicably busy and “un-Jewishly mute.”3 “For the Jew,” writes Susan Handelman, “God’s presence is inscribed or traced within a text, not a body. Divinity is located in language, not person.”4

Tempering this distinction between Latter-day Saint and Jewish thought, however, is the theme of God’s “word,” a thread that runs through every chapter in the Book of Moses. Continuing the discussion of the topic from a previous article,5 this Essay will explore the role of the divine word in Creation.

“There Are Many Worlds That Have Passed Away By the Word of My Power” (Moses 1:35)

The Lord’s description of the cosmic scale and endless continuum on which creation by the divine word transpires constitutes one of the most stunning aspects of the Visions of Moses. As noted previously, Hebrews 1:2 and 11:3 mention “worlds” in plural, but the phrases “worlds without number,”6 “many worlds,”7 and later “millions of earths like this”8 belong to the Book of Moses. This concept, as Draper, Brown, and Rhodes note, “was not a part of traditional Christian teaching”9 and a “doctrine unknown in the days of Joseph Smith.”10 These expressions and the statements in which they occur correspond to the chronological infinitude expressed by Isaiah as ʿad-ʿôlmê ʿad11 —sometimes translated “world without end” (KJV), “worlds without end,”12 or “to all eternity” (NRSV).

This imagery resonates with the cosmic picture being given us by contemporary astronomy and the deep-space telescopes more than anything else that we find in ancient scripture.13 The Lord mentions “many worlds” that are “innumerable … unto man” but “numbered unto me”—worlds cycling through a course of creation and uncreation:14

But only an account of this earth, and the inhabitants thereof, give I unto you. For behold, there are many worlds that have passed away by the word of my power. And there are many that now stand, and innumerable are they unto man; but all things are numbered unto me, for they are mine and I know them. … The heavens, they are many, and they cannot be numbered unto man; but they are numbered unto me, for they are mine. And as one earth shall pass away, and the heavens thereof even so shall another come; and there is no end to my works, neither to my words.

This language also resonates with Jesus’ words to his disciples as recorded in Matthew 24: “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away,”15 or as clarified in the Joseph Smith Translation (JST): “Although, the days will come, that heaven and earth shall pass away; yet my words shall not pass away, but all shall be fulfilled.”16 That last phrase, “but all shall be fulfilled,” added to the JST Matthew text represents one of the most important thematic aspects of the divine “word” in the Book of Moses. A revelation given to the Prophet Joseph Smith “beginning September 26, 1830,”17 quotes or paraphrases the text of Moses 1 revealed just months earlier: “But remember that all my judgments are not given unto men; and as the words have gone forth out of my mouth even so shall they be fulfilled, that the first shall be last, and that the last shall be first in all things whatsoever I have created by the word of my power, which is the power of my Spirit.”18 Jesus’s endless “words” in premortality, mortality, and postmortality are the ongoing creative process in the cosmos. He is the creative force.

Thus, the revelation to Moses of an endless procession of “earth[s] … and the heavens thereof” forestalls the notion that the “heavens and the earth [being] finished” in the forthcoming creation account somehow amounts to an end to divine creative activity, as Genesis 3:1 and the notion of “Sabbath”—from the Hebrew verb šābat, “cease,” “come to the end of an activity”—might seem to imply.19 As Jesus said to the Jerusalem religious elite who challenged his Sabbath day activities, “My Father worketh hitherto, and I work.”20 The Book of Moses’ view of the creative “Word” parallels its view of the written “words” of God with its implicit notion of “canon”: “there is no end to my works, neither to my words.” There is no end to creation. There is no end to scripture or revelation—the revealed word.21 The universe is an open canon.

“This I Did By the Word of My Power, and It Was Done as I Spake” (Moses 2:5)

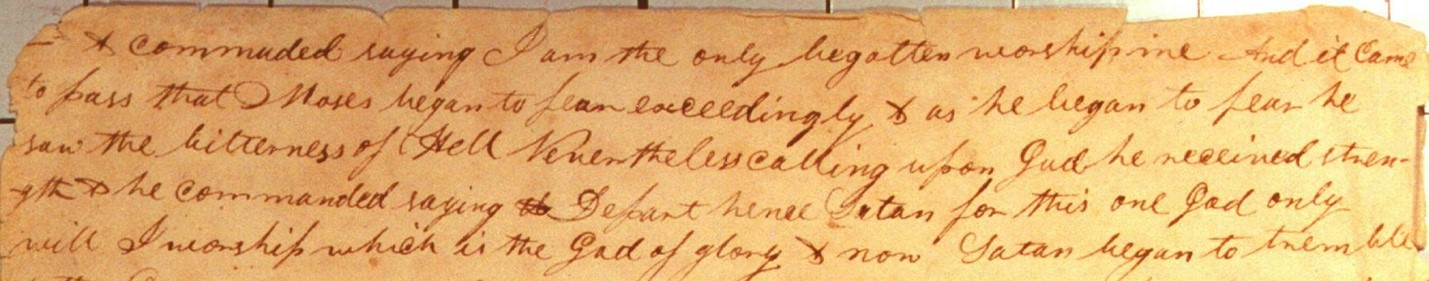

The Book of Moses transitions from the initial “Visions of Moses” to Joseph Smith’s inspired revision of the Genesis 1 creation account—which constitutes a continuation of the preceding vision—with the Lord commanding Moses to write his “words” and reemphasizing the executive role of the Only Begotten in in a never-ending creation process: “And it came to pass that the Lord spake unto Moses, saying: Behold, I reveal unto you concerning this heaven, and this earth; write the words [things] which I speak. I am the Beginning and the End, the Almighty God; by mine Only Begotten I created these things; yea, in the beginning I created the heaven, and the earth upon which thou standest.”22 The Lord’s ongoing words to Moses represent a continuation of his endless “words” and a never-ending creation—his “works.” This establishes the framework for the creation account in which the spoken word and the creative process remain eminently intertwined.

Kathleen Flake has observed that “like the Book of Mormon’s Israelite exodus to America, the JST’s creation narrative has always informed the Latter-day Saint ethos.”23 The Lord’s words in Moses 2:1 breathe new life into the abstract opening statement of the Hebrew Bible: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). The Lord himself appropriates “the beginning”—Hebrew rēʾšît—as a name-title for himself. Here too he is the subject of the verb “create”—Hebrew bārāʾ, the verb of which God is always the subject or implied agent in the Bible24 —but he takes personal ownership of his creative acts through the 1st person verb form. This invites comparison to the creation scenes in Isaiah 40-66,25 and the use of the first person in Isaiah 43:7, 45:8, 12; 54:16 (compare especially Isaiah 45:8, 12). Joseph Smith’s Genesis revision restores a backdrop that accommodates other creation texts in the Hebrew Bible like Psalms 148:5, 8: “for he commanded [ṣiwwâ], and they were created [wĕnibrāʾû] … Fire, and hail; snow, and vapour; stormy wind fulfilling his word [ʿōśâ dĕbārô].”

The closely correlated “works” and “words” of Moses 1:4-5, 48—“works” and “words” brought to pass through the “Word of my power”26 (Moses 1:32, 35; 2:5)—supplies additional revelatory context for the creation by the divinely spoken yĕhî, “Let there be” (Moses 2:3, 6, 9, 14), widely familiar from the Genesis account (Genesis 1:3, 6, 14). The tight pairing of the jussive yĕhî, “Let there be…” and wayhî “and there was” paints a dramatic verbal picture of the genetic relationship between “words” and “work.”27

The Septuagint (LXX) version of the Bible rendered Hebrew yĕhî with the verb genēthētō (hence the name of the book “Genesis”). The Vulgate translation rendered Greek genēthētō with the 3rd person “fiat,” whence the theological notion expressed as “creation by fiat.” Recognition of this verb form helps us to appreciate nature the Lord’s Prayer as a kind of “creation” text: “Thy will be done [Genēthētō to thelēma sou ]28 in earth, as it is in heaven.” Moreover, such recognition reframes Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane as a “creation”-type text: “thy will be done [genēthētō to thelēma sou].”29 Matthew certainly intended his audience to see the Lord’s prayer and Jesus’ prayer to the Father in Gethsemane as inextricably linked by the shared phrase genēthētō to thelēma sou. In submitting his will completely to the Father, Jesus effected and completed the atoning30 of the physical and spiritual creation, without which neither could “answer the end”31 or “fill the measure of [their] creation.”32

Notably, two JST passages further help us envisage the Lord’s prayer and Jesus’ prayer(s) in Gethsemane as “creation”-type texts. First, from the cross JST Matthew 27:54 records “… a loud voice, saying, Father, it is finished [tetelestai, John 19:3033 ], thy will is done, yielded up the ghost.” John 19:30 employs the same verbal root –teleō as the LXX creation account (“And the heavens and the earth and all their order [kosmos] were finished [synetelesthēsan] … And God finished [synetelesen] on the seventh day”). Jesus reports to the Father as he “finishes” a new creation before entering into “rest” on the Sabbath.34 The second passage returns the creation language of Jesus’ prayers to the premortal existence and the council in heaven (“in the beginning”) where Jesus, the Father’s “my Beloved and Chosen from the beginning,” humbled himself before the Father: “Father, thy will be done, and the glory be thine forever.”35 The close relationship between Jesus Christ’s roles as Creator and Redeemer, between creation and redemption, suddenly comes into stark focus.

The thematic use of the creation-by-word verb yĕhî in Genesis 1 inevitably ties the creative process to the divine name or Tetragrammaton, Yhwh (often rendered Jehovah or more recently Yahweh) and its meaning. Frank Moore Cross explains the form of the name Yhwh as “a causative imperfect of the Canaanite-Proto-Hebrew verb hwh/hwy ‘to be’”36 with the basic meaning “He creates” or “he who causes to happen.”37 David Noel Freedman and Michael P. O’Connor insist that “In Hebrew … yahweh must be a causative, since the dissimilation of yaqṭal to yiqṭal did not apply in Amorite [i.e., West Semitic], while it was obligatory in Hebrew. The name yahweh must therefore be in the Hebrew hiphil form. Although the causative of hwy is otherwise unknown in Northwest Semitic (with the exception of Syriac, which is of little relevance here), it seems to be attested in the name of the God of Israel.”38 Nevertheless, the precise origin of the name yhwh and its possible relationship to the Mesopotamian deity Ea (Enki) remains a matter of discussion and exploration.39

Whatever the case, the onomastic wordplay on Yhwh in terms of the verb form ʾehyeh (“And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM [ʾehyeh ʾăšer ʾehyeh]: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM [ʾehyeh] hath sent me unto you”) confirms that ancient Israelites thought of the name Yhwh in terms of the verb hwy/hyy, whatever the origin of the name Yhwh (or Yah). This constitutes the conceptual backdrop against which the foregoing jussive creation fiats (“let there be…”) should be understood: a name expressing the idea of creating or bringing to pass through the speaking of the very word of which the name itself is a manifestation.

In this vein, the text of Moses 2 reiterates the executive role of the Son in his accomplishing the divine will by means of the phrase “this I did by the word of my power”: “And I, God, called the light Day; and the darkness, I called Night; and this I did by the Word of my power, and it was done as I spake; and the evening and the morning were the first day.”40 The phrase “and it was done as I spake” here preserves and replicates the tight cause-effect relationship between word and work evident is the tight pairing of “I, God, said let there be … and there was”). Jeffrey M. Bradshaw suggests that the added phrase “this I did by the Word of my power” functions “as a more or less synonymous parallel to the expression that ‘it was done as I spake.”41 The reiterated variants of the stereotyped Genesis 1 phrase “and it was so [wayhî kēn]” in Moses 2—“and it was done” (v. 6); “and it was so even as I spake” (vv. 7, 11, 31); “and it was so” (vv. 9, 15, 24)—further emphasize the power of the divine “word” to bring to pass each divine “work.”

“And the Stars Also Were Made Even According to My Word” (Moses 2:16)

In addition to the “worlds without number” or “many worlds” which the Lord claims as his creations in Moses 1:33, 35, he avers his creation of the great luminaries in the heavens upon which those worlds necessarily depend. He accordingly makes the following geocentric statement regarding the creation of the luminaries: “And I, God, made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night, and the greater light was the sun, and the lesser light was the moon; and the stars also were made even according to my word.”42

Unlike the Genesis account, where the names of the great lights have been suppressed, possibly due to the connection of šemeš (“sun”; Ugaritic špš) and yārēaḥ (“moon”) with the divinized Sun (Shammash) and the divinized Moon (cf. Akkadian, Sîn), which were widely worshipped. Suppression of the names “sun” and “moon” in the biblical text is rendered superfluous in Book of Moses text with the declaration that the sun, moon, and stars all came into being “even according to my word.” God and his divine Word are the only deities that the text has in view. The divine passive, “were made according to my word” further allows for a very lengthy creative process. We see something similar in the Lord’s subsequent description of spiritual creation (cf. Moses 3:7).

Conclusion

Even some of the most doubting of scientists have stated their willingness to keep their mind open to the possibility of a God — so long as it is a God “worthy of [the] grandeur”43 of the Universe. For example, the well-known skeptic Richard Dawkins stated: “If there is a God, it’s going to be a whole lot bigger and a whole lot more incomprehensible than anything that any theologian of any religion has ever proposed.”44 Similarly, Elder Neal A. Maxwell approvingly quoted the unbelieving scientist Carl Sagan, noting that he:45

perceptively observed that “in some respects, science has far surpassed religion in delivering awe. How is it that hardly any major religion has looked at science and concluded, ‘This is better than we thought! The Universe is much bigger than our prophets said — grander, more subtle, more elegant. God must be even greater than we dreamed’? Instead, they say, ‘No, no, no! My god is a little god, and I want him to stay that way.’”

Joseph Smith’s God was not a little god. His God was a God who required our minds to “stretch as high as the utmost heavens, and search into and contemplate the darkest abyss, and the broad expanse of eternity”46 — that is more of a stretch than the best of us now can even imagine.

This article is adapted from Bowen, Matthew L. “‘By the word of my power’: The many functions of the divine word in the Book of Moses.” Presented at the conference entitled “Tracing Ancient Threads of the Book of Moses’ (September 18-19, 2020), Provo, UT: Brigham Young University 2020.

Further Reading

Bailey, David H., Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith, and Michael L. Stark, eds. Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016, pp. 259-351. https://archive.org/details/CosmosEarthAndManscienceAndMormonism1.

Bowen, Matthew L. “‘Creator of the first day’: The glossing of Lord of Sabaoth in Doctrine and Covenants 95:7.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 51-77. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/creator-of-the-first-day-the-glossing-of-lord-of-sabaoth-in-dc-957/.

Bowen, Matthew L. “‘By the word of my power’: The divine word in the Book of Moses.” Presented at the conference entitled “Tracing Ancient Threads of the Book of Moses’ (September 18-19, 2020), Provo, UT: Brigham Young University 2020.

Holland, Jeffrey R. “‘My words… never cease’.” Ensign 28, May 2008, 91-94. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2008/05/my-words-never-cease?lang=eng.

Maxwell, Neal A. “Our Creator’s Cosmos (Twenty-Sixth Annual Church Educational System Conference, Brigham Young University, 13 August 2002).” Religious Educator 3, no. 2 (August 13, 2002 2002): 1-17. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol3/iss2/3/.

References

Bailey, David H., Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith, and Michael L. Stark, eds. Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. https://archive.org/details/CosmosEarthAndManscienceAndMormonism1. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Barker, Margaret. The Great Angel: A Study of Israel’s Second God. Louisville, KY: Westminster / John Knox Press, 1992.

Blech, Benjamin, and Roy Doliner. The Sistine Secrets: Michelangelo’s Forbidden Messages in the Heart of the Vatican. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2008.

Botterweck, G. Johannes, Helmer Ringgren, and Heinz-Josef Fabry. Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. 11 vols. to date vols. Translated by John T. Willis and et_al., 1974-2001.

Bowen, Matthew L. “‘Creator of the first day’: The glossing of Lord of Sabaoth in Doctrine and Covenants 95:7.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 51-77. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/creator-of-the-first-day-the-glossing-of-lord-of-sabaoth-in-dc-957/. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. www.templethemes.net.

Chadwick, Jeffrey R. “Dating the death of Jesus Christ.” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2015): 135-91. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/dating-death-jesus-christ. (accessed September 5, 2020).

Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6e92/855210ba9dd75f919dbc166ab37da472cea9.pdf. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Ellis, Richard S. “Images at work versus words at play: Michelangelo’s art and the artistry of the Hebrew Bible.” Judaism 51, no. 2 (2002): 162-74. http://www.math.umass.edu/~rsellis/images-vs-words-long.html. (accessed August 9).

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Flake, Kathleen. “Translating time: The nature and function of Joseph Smith’s narrative canon.” Journal of Religion 87, no. 4 (October 2007): 497-527. http://www.vanderbilt.edu/divinity/facultynews/Flake%20Translating%20Time.pdf. (accessed February 22, 2009).

Gee, John. “The geography of Aramaean and Luwian Gods.” Presented at the Aramaean Borders Defining Aramaean Territories in the 10th – 8th Centuries BCE Conference Organized as Part of the Research Project GA ČR P401/12/G168 ‘History and Interpretation of the Bible,’ 22-23 April 2016, Prague, Czech Republic 2016. http://cbs.etf.cuni.cz/assets/files/Program%20Aramaean%20Borders.pdf. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Holland, Jeffrey R. “‘My words… never cease’.” Ensign 28, May 2008, 91-94. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2008/05/my-words-never-cease?lang=eng. (accessed July 9, 2020).

———. “‘My words… never cease’.” In Broken Things to Mend, edited by Jeffrey R. Holland, 184-90. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

Isaacson, Walter. Einstein: His Life and Universe. New York City, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Krauss, Lawrence M., and Richaard Dawkins. 2007. Should Science Speak to Faith? (Extended version). In Scientific American Online. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?chanId=sa013&articleID=44A95E1D-E7F2-99DF-3E79D5E2E6DE809C&modsrc=most_popular. (accessed July 27, 2007).

Maxwell, Neal A. “Our Creator’s Cosmos (Twenty-Sixth Annual Church Educational System Conference, Brigham Young University, 13 August 2002).” Religious Educator 3, no. 2 (August 13, 2002 2002): 1-17. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol3/iss2/3/. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Nugent, Tony Ormond. Star-god: Enki/Ea and the Biblical God as Expressions of a Common Ancient Near Eastern Astral-theological Symbol System (Ph.D. Dissertation). Syracuse, NY: Seracuse University, 1993. https://surface.syr.edu/rel_etd/52/. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Townes, Charles H. “The convergence of science and religion.” Improvement Era 71, February 1968, 62-69.

Van Biema, David. “God vs. Science (Debate between Richard Dawkins and Francis Collins).” Time, November 13 2006, 49-55.

Walton, John H. The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009.

Welch, John W. “”Thy mind, o man, must stretch”.” BYU Studies 50, no. 3 (2011): 63-81. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/thy-mind-o-man-must-stretch. (accessed September 6, 2020).

Wilson, Daniel J. “Wayhî and theticity in biblical Hebrew.” Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 45, no. 1 (2019): 89-118. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334441983_Wayhi_and_Theticity_in_Biblical_Hebrew. (accessed September 5, 2020).

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. Public domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo,_Creation_of_the_Sun,_Moon,_and_Plants_01.jpg.

Footnotes

1 J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 85-87.

2 B. Blech et al., Secrets, p. 195.

3 R. S. Ellis, Images.

4 Ibid.

5 Essay #42.

6 Moses 1:33.

7 Moses 1:35.

8 Moses 7:30.

9 R. D. Draper et al., Commentary, p. 33.

10 Ibid., p. 33.

11 Isaiah 45:17: “But Israel shall be saved in the LORD with an everlasting salvation: ye shall not be ashamed nor confounded world without end [ʿad-ʿôlmê ʿad].” Cf. Ephesians 3:21: “Unto him be glory in the church by Christ Jesus throughout all ages, world without end [tou aiōnos ton aiōnōn]. Amen.”

12 D&C 76:112 pluralizes KJV “world without end” as “worlds without end.”

13 D. H. Bailey et al., Science and Mormonism 1, pp. 259-351.

14 Moses 1:35, 37-38.

15 Matthew 24:35.

16 Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:35.

17 From the heading to Doctrine and Covenants 29 (2013 edition).

18 Doctrine and Covenants 29:30.

19 J. H. Walton, Lost World of Genesis One, pp. 73-74. See also M. L. Bowen, Creator of the First Day. Walton writes:

The Hebrew verb šābat (Genesis 2:2) from which our term “sabbath” is derived has the basic meaning of ‘ceasing’ (Joshua 5:12; Job 32:1). Semantically it refers to the completion of certain activity with which one had been occupied. This cessation leads into a new state which is described by another set of words, the verb nûḥa and its associated noun mĕnûḥâ. The verb involves entering a position of safety, security, or stability, and the noun refers to the place where that is found. The verb šābat describes a transition into the activity or inactivity of nûḥa. We know that when God rests (ceases, šābat) on the seventh day in Genesis 2, he also transitions into the condition of stability (nûḥa) because that is the terminology used in Exodus 20:11. The only other occurrence of the verb šābat with God as the subject is in Exodus 31:17. The most important verses to draw all of this information together are found in Psalm 132:7-8, 13-14:

Let us go to his dwelling place

Let us worship at his footstool—

‘Arise, O Lord, and come to your resting place,

you, and the ark of your might.’

For the Lord has chosen Zion,

he has desired it for his dwelling:

‘This is my resting place for ever and ever;

here I will sit enthroned for I have desired it.’Here the ‘dwelling place’ of God translates a term that describes the tabernacle and temple, and it is where his footstool (the ark) is located. … Thus, this Psalm pulls together the ideas of divine rest, temple, and enthronement. God’s ‘ceasing’ (šābat) on the seventh day in Genesis 2:2 leads to his “rest” (nûḥa), associated with the seventh day in Exodus 2:11. His ‘rest’ is located in his ‘resting place’ (mĕnûḥâ) in Psalm 132. After creation, God takes up his rest and rules from his residence. This is not new theology for the ancient world—it is what all people understood about their gods and their temples.

20 John 5:17.

21 See, e.g., J. R. Holland, Words; J. R. Holland, Words (Broken).

22 Moses 2:1.

23 K. Flake, Translating Time, p. 503.

24 Genesis 1:5, 21, 27; 2:3-4; 5:1-2; 6:7; Exodus 34:10 (God implied subject of passive verb forms); Numbers 16:30; Deuteronomy 4:32; Psalm 51:10; 89:12, 47; 102:18; 104:30; 148:5; Ecclesiastes 12:1; Isaiah 4:5; 40:26, 28; 41:20; 42:5; 43:1, 7, 15; 45:7-8, 12, 18; 48:7; 54:16; 57:19; 65:17-18; Jeremiah 31:22; Ezekiel 21:19, 30; 28:13, 15; Amos 4:13; Malachi 2:10.

25 See, e.g., Isaiah 40:6, 8; 41:20; 42:5; 43:1, 7, 15; 45:7-8, 12, 18; 48:7; 54:16; 57:19; 65:17-18.

26 “Word” in “Word of my power” is capitalized in OT1 at Moses 2:5 (S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, OT1 Page 3 (Moses 1:37-2:12), p. 86).

27 Cf. D. J. Wilson, Wayhî and Theticity.

28 Matthew 6:10; Luke 11:2.

29 Matthew 26:42.

30 Cf. Deuteronomy 32:43: “[The Lord] will be merciful unto [wĕkipper, literally, atone] his land, and … his people. M. Barker (The Great High Priest, p. 31-32) writes: “The principle of temple practice, ‘on earth as it is in heaven,’ meant that the act of atonement, in reality the work of the Lord (Deut. 32:43), was enacted on earth by the high priest. This was the suffering and death that was necessary for the Messiah.”

31 D&C 49:16.

32 D&C 88:19, 25.

33 John 19:28-30: “After this, Jesus knowing that all things were now accomplished, that the scripture might be fulfilled, saith, I thirst. Now there was set a vessel full of vinegar: and they filled a sponge with vinegar, and put it upon hyssop, and put it to his mouth. When Jesus therefore had received the vinegar, he said, It is finished: and he bowed his head, and gave up the ghost.”

34 This observation holds whether Jesus died on Friday (traditional) or on Thursday as argued recently in J. R. Chadwick, Dating the Death. See also Mark 15:42; Luke 23:54-56; John 19:31.

35 Moses 4:2.

36 F. M. Cross, Canaanite Myth, p. 65.

37 M. Barker, Angel, p. 104.

38 David Noel Freedman and Michael P. O’Connor, “YHWH” in G. J. Botterweck et al., TDOT, 5:513.

39 T. O. Nugent, Star-god; J. Gee, Geography of Aramaean and Luwian Gods

40 Moses 2:5.

41 J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, p. 102. Bradshaw writes, “Two interpretations are possible. On the one hand, this phrase, added in the book of Moses, can be seen as a more or less synonymous parallel to the expression that ‘it was done as I spake.’ On the other hand, it could be taken to indicate that the light and darkness were ‘made’ in a different fashion than the entities created on subsequent days.”

42 Moses 2:14.

43 R. Dawkins in D. Van Biema, God vs. Science, p. 55. As a matter of scientific principle, Dawkins has classed himself as a TAP (Temporary Agnostic in Practice), though he thinks the probability of a God is very small, and certainly in no sense would want to be “misunderstood as endorsing faith” (L. M. Krauss et al., Science (online)).

44 L. M. Krauss et al., Science (online). Though personally rejecting the notion of a personal God, Albert Einstein is an example of one whose deeply-held “vision of unity and order” (C. H. Townes, Convergence, p. 66) — which throughout his life played an important role in shaping his scientific intuitions (see, e.g., W. Isaacson, Einstein, p. 335) — was chiefly motivated by his profound sense of awe and humility in the face of the lawful and “marvelously arranged” universe (ibid., p. 388):

Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the Universe—a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modest powers must feel humble.

Often more critical of the debunkers of religion than of naïve believers in God, he explained: “The fanatical atheists are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who—in their grudge against traditional religion as the ‘opium of the masses’ — cannot hear the music of the spheres” (ibid., p. 390).

45 N. A. Maxwell, Cosmos, p. 1.

46 See J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 25 March 1839, p. 137. For an insightful discussion of this imperative, see J. W. Welch, Thy Mind.