Book of Abraham Insight #33

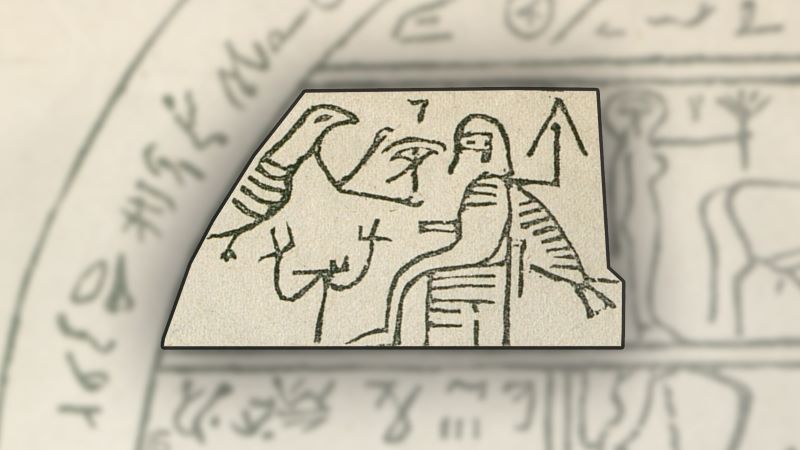

Figure 7 in Facsimile 2 is identified as follows: “Represents God sitting upon his throne, revealing through the heavens the grand Key-words of the Priesthood; as, also, the sign of the Holy Ghost unto Abraham, in the form of a dove.” Appearing in several other ancient Egyptian hypocephali,1 the sitting personage in Figure 7 has been described by one Egyptologist as “a polymorphic god sitting on his throne” with “the back of him is bird-form, while one of his arms is raised [in] the attribution” of the gods Min or Amun “and hold[ing] forth a flagellum.” Standing next to him is a “falcon- or snake-headed snake” believed to perhaps be the minor deity Nehebkau, who “offers the wedjat-eye.”2

Another Egyptologist has similarly described this figure as “a seated ithyphallic god with a hawk’s tail, holding aloft a flail. This is a form of Min . . . perhaps combined with Horus, as the hawk’s tail would seem to indicate. Before the god is what appears to be a bird presenting him with a Wedjat-eye.”3 In some hypocephali the ancient Egyptians themselves simply identified this figure as, variously, the “Great God” (nṯr ˁȝ), the “Lord of Life” (nb ˁnḫ), or the “Lord of All” (nb r ḏr).4 This first epithet is significant for Joseph Smith’s interpretation, since in one ancient Egyptian text the divine figure Iaho Sabaoth (Lord of Hosts) is also afforded the epithet “the Great God” (pȝ nṯr ˁȝ).5

Since some Egyptologists have suggested this figure is the god Min or Amun, who was often syncretized with Min,6 it would be worth exploring what we know about this deity, even if this identification wasn’t explicitly made by the ancient Egyptians themselves. One of Egypt’s oldest gods, Min was worshipped as early as the Pre-Dynastic Period (circa pre-3000 BC). Although he assumed multiple attributes over millennia,7 Min is perhaps best known as “the god of the regenerative, procreative forces of nature”8; that is, as a sort of fertility god who was often depicted as the premier manifestation of “male sexual potency.”9 He is frequently shown raising his arm to the square while holding a flail, symbols or gestures associated with kingship, displaying power, and the ability to protect from enemies.10

Min is also very often, though not always,11 depicted in hypocephali with an erect phallus (ithyphallic), which Egyptologists have interpreted as either a symbol of, on the one hand, sexual potency, fertility, (pro)creation, and rejuvenation, or, on the other hand, aggression, power, and potency.12 One Egyptologist has also interpreted depictions of Min with his raised arm and erect phallus as a sign of him being “a protector of the temple” whose role was to “repulse negative influences from the ‘profane surroundings’” of the sacred space of the temple.13

That Min would assume the roles of divine procreator who gives life and divine king who upholds the cosmos is understandable from the viewpoint of ancient Egyptian religion.14 As Ian Shaw explains,

Although Egyptian art shied away from depicting the sexual act, it had no such qualms about the depiction of the erect phallus. . . . The three oldest colossal religious statues in Egyptian history, found by [William Flinders] Petrie in the earliest strata of the temple of Min at Koptos . . . where essentially large ithyphallic representations, probably of Min. . . . This celebration of the phallus appears to be directly related to the Egyptians’ concerns with the creation (and sustaining) of the universe, in which the king was thought to play a significant role—which was no doubt one of the reasons why the Egyptian state would have been concerned to ensure that the ithyphallic figures continued to be important elements in many cults.15

Christina Riggs similarly comments that “near naked goddesses, gods with erections, and cults for virile animals, like bulls, make sense in [ancient Egyptian] religious imagery because they captured the miracle of life creating new life.”16 For this reason Min was “regarded as the creator god par excellence” in ancient Egypt, as fertility and (male) sexuality was “subsumed under the general notion of creativity.”17

Figure 7 in Facsimile 2 was either originally drawn or copied somewhat crudely (without access to the original it is impossible to tell), and so it is not entirely clear if the seated figure is ithyphallic or if he has one arm at his side with the other arm clearly raised in the air. Although Egyptologists have tended to interpret Figure 7 in Facsimile 2 as ithyphallic—and that seems to be how it is depicted—it should be kept in mind, as noted above (and seen below), that Min is not always depicted as such in hypocephali, so he need not necessarily be viewed as ithyphallic in Facsimile 2. In any case, there is nothing to suggest anything pornographic or sexually illicit in ancient ithyphallic depictions of Min.

But what about the figure assumed to be Nehebkau offering Min the Wedjat-eye?18 Depicted most commonly as a snake or snake-headed man19—but sometimes as a falcon (as in Facsimile 2)20—in Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, Nehebkau is named as one of the judges of the dead.21 In Chapter 149 of the Book of the Dead he is associated with Min and other deities as one who assures the dead will be rejuvenated and resurrected with a perfected body.22 In the Pyramid Texts he feeds the deceased king and acts as a divine messenger.23 As such, he “was considered to be a provider of life and nourishment.”24 Together Nehebkau and Min ”were symbolic of life-force and procreative forces of nature.”25

In ancient Egyptian, wḏȝ carries the meaning of “hale, uninjured,” and “well-being.”26 The word can describe the health or wholeness of the physical body, the soul, or moral character.27 The wḏȝt-eye Nehebkau presents to Min (or vice-versa) was envisioned by the ancient Egyptians as “whole” or “sound” eye of Horus and had an apotropaic function in ancient Egyptian religion.28 It was, in short, “the symbol of all good gifts”29 and a symbol for “the miracle of [the] restoration” and renewal of the body.30

This fuller understanding helps make sense of Joseph Smith’s interpretation of this figure and plausibly situates such it in an ancient Egyptian context.31

Further Reading

Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 19 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2010), 304–322.

Michael D. Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…20 Years Later,” FARMS Preliminary Paper (1997).

Footnotes

1 Tamás Mekis, Hypocephali, PhD diss. (Eötvös Loránd University, 2013), 1:91–93.

2 Mekis, Hypocephali, 1:91.

3 Michael D. Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…20 Years Later,” FARMS Preliminary Paper (1997), 11.

4 John Gee, “Towards an Interpretation of Hypocephali,” in “Le Lotus Qui Sort de Terre”: Mélanges Offerts À Edith Varga, ed. Hedvig Győry (Budapest: Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts, 2001), 334; Mekis, Hypocephali, 1:91n484.

5 John Gee, “The Structure of Lamp Divination,” in Acts of the Seventh International Conference of Demotic Studies, Copenhagen, 23–27 August 1999, ed. Kim Ryholt (Copenhagen: The Carsten Neibuhr Institute of Near Eastern Studies, University of Copenhagen, 2002), 211–212.

6 Christian Leitz, ed., Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen (Leuven: Peeters, 2002), 3:290–291.

7 Leitz, Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, 3:288–291.

8 Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…20 Years Later,” 11.

9 Eugene Romanosky, “Min,” in The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion, ed. Donald B. Redford (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 218.

10 Leitz, ed., Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, 3:288; Jorge Ogdon, “Some Notes on the Iconography of Min,” Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 7 (1985/6): 29–41; Romanosky, “Min,” 219; Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt (London: Routledge, 1999), 161; Manfred Lurker, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 52. Richard H. Wilkinson, Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 196; cf. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 115; “Ancient Near Eastern Raised-Arm Figures and the Iconography of the Egyptian God Min,” Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 11 (1991–2): 109–118.

11 Mekis, Hypocephali, 1:92.

12 Ogdon, “Some Notes on the Iconography of Min,” 29–41; Joachim Quack, “The So-Called Pantheos: On Polymorphic Deities in Late Egyptian Religion,” in Aegyptus et Pannonia III: Acta Symposii anno 2004, ed. Hedvig Győry (Budapest: Comité de l’Égypte Ancienne de l’Association Amicale Hongroise-Égyptienne, 2006), 176.

13 Ogdon, “Some Notes on the Iconography of Min,” 33.

14 Min was often syncretized with both Horus and Amun, two gods closely associated with kingship, and himself bore the epithet “Min the King.” Leitz, Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, 3:290–291.

15 Ian Shaw, Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 133.

16 Christina Riggs, Ancient Egyptian Art and Architecture: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 89.

17 K. Van der Toorn, “Min,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst, 2nd ed. (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 557. This can be further seen in the Pyramid Texts, which explicitly links male sexual virility with the creation of the cosmos (in this case the birth of Shu and Tefnut from the primordial creator god Atum). PT 527 in James Allen, trans., The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, ed. Peter Der Manuelian (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005), 164.

18 Alan W. Shorter, “The God Nehebkau,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 21, no. 1 (1935): 41–48; Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 224–225.

19 Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, 224; Leitz, Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, 4:274.

20 Mekis, Hypocephali, 1:92n486; Leitz, Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, 4:274.

21 Raymond O. Faulkner, trans., The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead (London: The British Museum Press, 2010), 32; Karl Richard Lepsius, Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter nach dem hieroglyphischen Papyrus in Turin mit einem Vorworte zum ersten Male Herausgegeben (Leipzig, Germany: G. Wigand, 1842), Pl. XLVII.

22 Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, 137; Lepsius, Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter, Pl. LXXI.

23 PT 264, PT 609 in Allen, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, 78, 230.

24 Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…20 Years Later,” 12.

25 Luca Miatello, “The Hypocephalus of Takerheb in Firenze and the Scheme of the Solar Cycle,” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 37 (2008): 285.

26 Raymond O. Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 1962), 74–75.

27 Adolf Erman and Hermann Grapow, Wörterbuch der aegyptischen Sprache (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1958), 1:399–400.

28 Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002), 131–132.

29 Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…20 Years Later,” 11.

30 Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 19 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2010), 314.

31 See further Nibley and Rhodes, One Eternal Round, 304–322.