Book of Abraham Insight #35

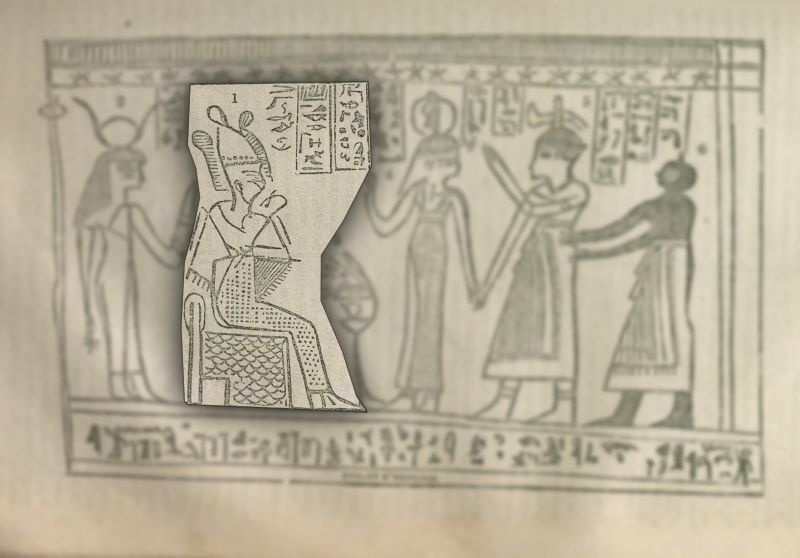

F igure 1 of Facsimile 3 of the Book of Abraham was interpreted by Joseph Smith as, “Abraham sitting upon Pharaoh’s throne, by the politeness of the king; with a crown upon his head, representing the priesthood; as emblematical of the grand presidency in heaven; with the scepter of justice, and judgment in his hand.” This interpretation has clashed with those offered by Egyptologists, who have instead identified the figure as the god Osiris.1 What’s more, two Egyptologists have claimed to arrive at this interpretation from reading the hieroglyphs to the right of Figure 1.2

Robert Ritner (2011) | Michael Rhodes (2002) |

ḏd-mdw ỉ(n) Wsỉr ẖnty-ỉmnty.w nb(?) ȝbḏw(?) nṯr ˁȝ r ḏ.t nḥḥ(?) Recitation by Osiris, Foremost of the Westerners, Lord of Abydos(?), the great god forever and ever(?). | ḏd-mdw ỉ(n) Wsỉr ẖnty-ỉmnty.w mn=k, Wsỉr, Ḥr m ns.t ˁȝ.ṯ=f Words spoken by Osiris, the Foremost of the Westerners: May you, Osiris Hor, abide at the side of the throne of greatness. |

One of these Egyptologists has attempted to reproduce the hieroglyphs accompanying Figure 1.3 A comparison of his reproduction and Reuben Hedlock’s original, however, reveals some difficulties.

For example, some of the glyphs in the name of Osiris in the first column on the right only bear general resemblance to attested spellings of Osiris’ name in other copies of the Book of Breathings, and other glyphs that make up the rest of the name and epithets for Osiris look quite different as well.4 “These issues combine to suggest that the translation of the characters may not be as straightforward as has been previously assumed,” so “while one can see good reasons for . . . the use of parallel texts”5 to reconstruct illegible characters in Facsimile 3, it is also necessary to be aware of difficulties or uncertainties in reading the hieroglyphs in Hedlock’s copy of Facsimile 3.6

Nevertheless, the identity of this figure as Osiris appears reasonable based on comparable iconography. One might therefore rightly ask how or even if it is possible to reconcile Joseph Smith’s identification of this figure as Abraham.

In 1981, Latter-day Saint scholar Blake T. Ostler drew attention to possible Egyptian connections between the figures of Osiris and Abraham.7 For example, Ostler cited the work of an earlier non-Latter-day Saint German scholar drawing parallels between the parable of Lazarus and the rich man in Luke 16:19–31 and an Egyptian text known as the tale of Setne.8 As summarized more recently by another Latter-day Saint scholar, in the Egyptian text, a boy named Si-Osiris (“son of Osiris”) and his father witness “two funerals: first, that of a rich man, shrouded in fine linen, loudly lamented and abundantly honored; then, that of a poor man, wrapped in a straw mat, unaccompanied and unmourned. The father says that he would rather have the lot of the rich man than that of the pauper.”9 To show his father the folly of his thinking, Si-Osiris takes him to the underworld, where the rich man who had an elaborate funeral is punished while the pauper who had no dignified burial is glorified and exalted in the presence of the god Osiris himself. “The reason for this disparate treatment is that, at the judgment, the good deeds of the pauper outweighed the bad, but with the rich man the opposite was true.”10

Some scholars have argued for a Jewish borrowing and adaptation of the tale of Setne that made its way into the Gospel of Luke. Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim introduces her translation of the tale of Setne by commenting on the “genuinely Egyptian motifs” of the nobleman who is tortured in the netherworld while the poor man is deified in the afterlife. These motifs, she insists, “formed the basis for the parable of Jesus in Luke 16, 19–31, and for the related Jewish legends, preserved in many variants in Talmudic and medieval Jewish sources.”11

Another scholar has further explored the parallels between these two traditions and notes how Lazarus being exalted in “the bosom of Abraham” in Luke’s retelling of the parable is very likely a Jewish refashioning of the imagery in the tale of Setne of the poor beggar being found exalted by the throne of Osiris. In his words, “‘Abraham’ must be a Jewish substitute for the pagan god Osiris. He is the very seat of divine authority” in the parable, “for he was originally the lord of Amnte, Osiris.”12 Even the name Lazarus is likely the Greek rendering of the Hebrew-Aramaic “God-helped-(him)” (אלעזר/לעזר), which “points back toward an Egyptian original with similar meaning: ‘Osiris-helps-him’, for instance.”13

As explained by Barney, “We are able to see how the Egyptian story has been transformed in Semitic dress. . . . The ‘bosom of Abraham’ [from the Lucan parable] represents . . . the Egyptian abode of the dead. And, most remarkably, Abraham is a Jewish substitute for the pagan god Osiris—just as is the case in Facsimiles 1 and 3.”14

There appears to be another instance of the biblical figure Abraham anciently being associated with the Egyptian god Osiris. As explained by Egyptologist John Gee, an Egyptian funerary formula found in several sources was later syncretized with Jewish figures in its later renderings into Greek and Coptic. The short Demotic version of the formula reads: “May his soul live in the presence of Osiris-Sokar the great god, the lord of Abydos” (ˁnḫ pȝ by=f m bȝḥ wsir skr pȝ nṯr ˁȝ nb ỉbḏw). In Greek this formula was later rendered as: “Rest his soul in the bosom of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob” (ἀναπαύσον τὴν ψυχὴν αὐτοὺ εἰς κόλπις Αβρααμ κ(αὶ) Ισαακ κ(αὶ) Ιακωβ). In this reformulation, “The expression ‘live in the presence of Osiris’ has been replaced by the expression ‘rest in Abraham’s bosom.”15

We cannot know exactly why Abraham was viewed by some anciently as a substitute for the Egyptian god Osiris.16 Whatever the case, “there are enough instances where Abraham appears in contexts normally occupied by Osiris that we must conclude the Egyptians saw some sort of connection.”17 It is especially noteworthy, as seen above, that Abraham appears as a substitute for Osiris in ways associated with the judgment of the dead or a postmortem declaration of the deceased’s worthiness. This in turn might shed some insight into what might otherwise appear as Joseph Smith’s incongruous interpretation of this figure in Facsimile 3.

Further Reading

Kevin L. Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 107–130.

Blake T. Ostler, “Abraham: An Egyptian Connection,” FARMS Report (1981).

Footnotes

1 See for instance Klaus Baer, “The Breathing Permit of Hôr: A Translation of the Apparent Source of the Book of Abraham,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3, no. 3 (Autumn 1968): 126; Michael D. Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 23.

2 Robert K. Ritner, The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri, A Complete Edition: P. JS 1–4 and the Hypocephalus of Sheshonq (Salt Lake City, UT: The Smith–Pettit Foundation, 2011), 139; Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings, 25.

3 Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings, 24.

4 Quinten Zehn Barney, The Neglected Facsimile: An Examination and Comparative Study of Facsimile No. 3 of The Book of Abraham, MA thesis, Brigham Young University (2019), 45, 121–122.

5 Barney, The Neglected Facsimile, 49.

6 Barney, The Neglected Facsimile, 45. Ritner’s hesitation in his reading of the hieroglyphs in Facsimile 3, as well as the multiple disagreements with Rhodes’ own reading of the same, further indicates the difficulty in reading these glyphs.

7 Blake T. Ostler, “Abraham: An Egyptian Connection,” FARMS Report (1981).

8 Ostler, “Abraham,” 3–8, citing Hugo Greßmann, Vom reichen Mann und armen Lazarus: Eine literargeschichtliche Studie (Berlin: Königliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1918).

9 Kevin L. Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 120–121.

10 Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” 121.

11 Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume III: The Late Period (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1980), 125–126; cf. Robert K. Ritner, “The Adventures of Setna and Si-Osire (Setna II),” in The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry, ed. William Kelly Simpson, 3rd ed. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003), 470–471.

12 K. Grobel, “…Whose name was Neves,” New Testament Studies 10 (1964): 380.

13 Grobel, “…Whose name was Neves,” 381.

14 Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” 121.

15 John Gee, “A New Look at the ˁnẖ pȝ by Formula,” in Actes du IXe congrès international des études démotiques, Paris, 31 août–3 septembre 2005, ed. Ghislaine Widmer and Didier Devauchelle (Paris: Institut Français D’Archaéologie Orientale, 2009), 143.

16 It should be noted that the ancient association between Abraham and Osiris is not the only attested instance of Judeo-Egyptian syncretization. As Gary Rendsburg has pointed out, “the biblical writer utilized the venerable Horus myth in order to present Moses as the equal to Pharaoh.” As seen in many parallels between the two figures, “the young Moses [in the biblical account] is akin to the young Horus, the latter a mythic equal of the living Pharaoh.” Gary A. Rendsburg, “Moses as Equal to Pharaoh,” in Text, Artifact, and Image: Revealing Ancient Israelite Religion, ed. Gary Beckman and Theodore J. Lewis (Providence, RI: Brown University, Brown Judaic Studies, 2010), 201–219, quote at 208.

17 Kerry Muhlestein, “Abraham, Isaac, and Osiris-Michael: The Use of Biblical Figures in Egyptian Religion, A Survey,” in Achievements and Problems of Modern Egyptology: Proceedings of the International Conference Held in Moscow on September 29–October 2, 2009, ed. Galina A. Belova (Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, Center for Egyptological Studies, 2009), 251.