Book of Abraham Insight #27

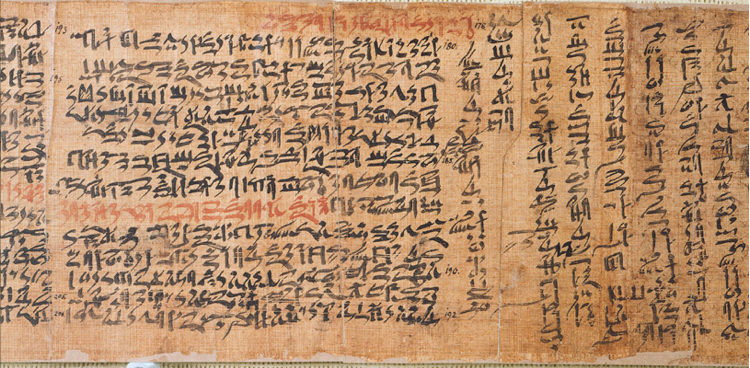

As “the only illustrations in our scriptures” the facsimiles of the Book of Abraham “attract attention not only because of their rough-hewn quality but by their very existence as a visual medium in the midst of the written word.”1 Latter-day Saint scholars and interested laypersons have offered a number of different approaches to understanding the facsimiles and gauging the validity of Joseph Smith’s interpretations thereof.2 Some of the more common approaches include:

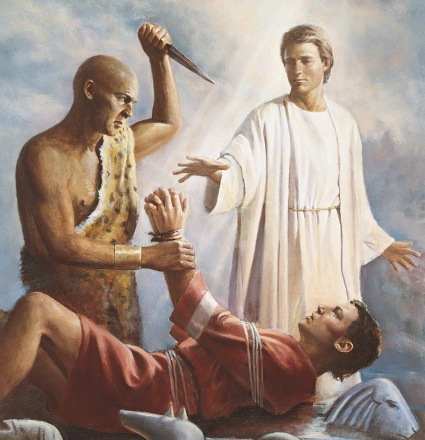

- The illustrations were original to Abraham. To interpret them we should look to how Egyptians in Abraham’s day, or Abraham himself, would have understood them.

- The illustrations were original to Abraham but were modified over time for use by the ancient Egyptians. The illustrations we have as preserved in the facsimiles are much later and altered copies of Abraham’s originals. To interpret them we should consider the underlying Abrahamic elements and compare them with how the Egyptians understood these images.3

- The illustrations were connected to the Book of Abraham when the Joseph Smith Papyri were created in the Ptolemaic period (circa 300–30 BC). To interpret them we should look to what Egyptians of that time thought these drawings represent.4

- The illustrations were connected to the Book of Abraham for the first time in the Ptolemaic period, but to interpret them we should look specifically to what Egyptian priests who were integrating Jewish, Greek, and Mesopotamian religious practices into native Egyptian practices would have thought about them.5

- The illustrations were connected to the Book of Abraham in the Ptolemaic period, but to interpret them we should look to how Jews of that era would have understood of them.6

- The illustrations were never part of the ancient text of the Book of Abraham, but instead were adapted by Joseph Smith to artistically depict the ancient text he revealed/translated. We can make sense of Joseph’s interpretations by expanding our understanding of his role as a “translator.”7

Each of these approaches has its respective strengths and weaknesses, but none on its own can account for all of the available evidence. For example, the first paradigm (1) is a more straightforward way of thinking about the facsimiles but is severely undermined by the fact that the Joseph Smith Papyri date to many centuries after Abraham’s lifetime.8 The second, third, and fourth paradigms (2–4) are each compelling to varying degrees since they can account for the instances where Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles align with other Egyptologists, but no single one of them can account for his interpretations in their entirety from an Egyptological perspective.

Whichever paradigm one adopts, it seems clear that Joseph Smith’s explanations to the facsimiles were original to himself (none of the explanations appear as text next to the illustrations on the papyri he possessed).9 “There are aspects of [these explanations] that match what Egyptologists say they mean. Some [of them] are quite compelling. . . . . However, as we look at the entirety of any of the facsimiles, an Egyptological interpretation does not match what Joseph Smith said about them.”10 This is, however, complicated by the fact that even though none of Joseph Smith’s explanations to the facsimiles in their entirety agree with how modern Egyptologists understand these illustrations, in many instances they do accurately reflect ancient Egyptian and Semitic concepts.11 This requires us to carefully unpack the assumptions we bring when approaching the facsimiles under any of the theoretical paradigms listed above.

Despite some important advances in scholarship, “we [still] do not [entirely] know to what we really should compare the facsimiles.”

Was Joseph Smith giving us an interpretation that ancient Egyptians would have held, or one that only a small group of priests interested in Abraham would have held, or one that a group of ancient Jews in Egypt would have held, or something another group altogether would have held, or was he giving us an interpretation we needed to receive for our spiritual benefit regardless of how any ancient groups would have seen these? We do not know. While [scholars] can make a pretty good case for the idea that some Egyptians could have viewed Facsimile 1 the way Joseph Smith presents it, [we are still] not sure that is the methodology we should be employing. We just don’t know enough about what Joseph Smith was doing to be sure about any possible comparisons, or lack thereof.12

What is clear from all of this is that “much more work needs to be done before we can understand the facsimiles in their ancient Egyptian setting, and only then will it be meaningful to ask whether that understanding matches that of Joseph Smith (to the extent that we understand even that).”13 For example, “Facsimile 3 has always been the most neglected of the three facsimiles in the Book of Abraham. Unfortunately, most of what has been said about this facsimile is seriously wanting at best and highly erroneous at worst.”14 Some valuable work in recent years, however, has helped remedy this by better situating this facsimile in its ancient Egyptian context.15 As that context has become clearer, elements of Joseph Smith’s explanations have become more plausible (although other elements remain at odds with current Egyptological theories).

Whichever theoretical paradigm one adopts in approaching the facsimiles, a respectable case can be made that with a number of his explanations Joseph Smith accurately captured ancient Egyptian concepts (and even scored a few bullseyes) that would have otherwise been beyond his natural ability to know.16 Any honest approach to the facsimiles must recognize this and take this into account. At the same time, however, this is not necessarily conclusive evidence that the facsimiles themselves were actually used as illustrations for Abraham’s record in antiquity. For now, then, the best approach to the facsimiles would be to remain open-minded and inquisitive and to keep asking the best questions that we can based on the best available evidence and information.

Further Reading

John Gee, “A Method for Studying the Facsimiles,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 347–353.

Kevin L. Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 107–130.

Michael D. Rhodes, “Teaching the Book of Abraham Facsimiles,” Religious Educator 4, no. 2 (2003): 115–123.

Footnotes

1 John Gee, “A Method for Studying the Facsimiles,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 347.

2 John Gee, A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 33–41; “A Method for Studying the Facsimiles,” 347–353; “The Facsimiles,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 143–156; Hugh Nibley, “What, Exactly, Is the Purpose and Significance of the Facsimiles in the Book of Abraham?” Ensign, March 1976, 34–36; “The Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham: A Response,” in An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2009), 493–501; Michael D. Rhodes, “Teaching the Book of Abraham Facsimiles,” Religious Educator 4, no. 2 (2003): 115-123; “Facsimiles from the Book of Abraham,” in The Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 Vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:135–137; Kevin L. Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 107–130; Allen J. Fletcher, A Study Guide to the Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, Inc., 2006); Terryl Givens, The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism’s Most Controversial Scripture (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 142–153.

3 Rhodes, “Teaching the Book of Abraham Facsimiles,” 115–123.

4 Gee, “A Method for Studying the Facsimiles,” 347–353.

5 Kerry Muhlestein, “The Religious and Cultural Background of Joseph Smith Papyrus I,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 1 (2013): 20–33.

6 Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” 107–130.

7 Givens, The Pearl of Greatest Price, 180–202.

8 Michael D. Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002), 3.

9 With regard to the authorship of the explanations of the facsimiles, it should be kept in mind that “[w]hile we do not know if Joseph Smith is the original author of these interpretations, we know he participated in preparing the published interpretations and gave editorial approval to them.” Kerry Muhlestein, “Joseph Smith’s Biblical View of Egypt,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 469n10.

10 Stephen Smoot, “Egyptology and the Book of Abraham: An Interview with Egyptologist Kerry Muhlestein,” FairMormon Blog (November 14, 2013).

11 In addition to the sources cited above, see additionally Michael D. Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…Twenty Years Later,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1997); John Gee, “Abracadabra, Isaac, and Jacob,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 7, no. 1 (1995): 19–84; Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2010).

12 Smoot, “Egyptology and the Book of Abraham.”

13 Gee, “A Method for Studying the Facsimiles,” 353.

14 John Gee, “Facsimile 3 and Book of the Dead 125,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2005), 95.

15 Gee, “Facsimile 3 and Book of the Dead 125,” 95–105; Quinten Zehn Barney, “The Neglected Facsimile: An Examination and Comparative Study of Facsimile No. 3 of The Book of Abraham,” MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 2019.

16 “Egyptian was not really understood in Joseph Smith’s day. Not a single inscription in either hieratic or hieroglyphs had been completely translated before his death, and none were published until seven years afterwards. Joseph Smith was not in the tradition of Champollion to which Egyptology today belongs. Any knowledge he may have had did not come from that source, and indeed, everyone is in agreement about that.” John Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” in Approaching Antiquity, 443.