Book of Abraham Insight #4

The opening verse of the Book of Abraham places the story “in the land of the Chaldeans” (Abraham 1:1). Several references to the city of Ur and “Ur of the Chaldees” are also present in the text (Abraham 1:20; 2:1, 4, 15; 3:1). This location is said to be the “residence of [Abraham’s] fathers” and Abraham’s own residence and “country” (Abraham 1:1; 2:3).

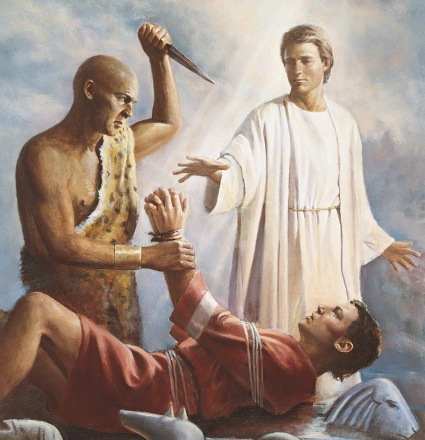

The Book of Abraham gives some specific details about Ur and this “land of the Chaldeans” that are not found in the Genesis account (Genesis 11:26–32; 12:1–5). This includes an apparent degree of Egyptian cultural and religious influence in the area (Abraham 1:6, 8–9, 11, 13) and being in or near the vicinity of “the plain of Olishem” (Abraham 1:10).

Where exactly is Abraham’s “Ur of the Chaldees”? For centuries, the traditional location for Muslims, Jews, and Christians was the city of Urfa (modern Sanliurfa in southeast Turkey). In the 1920s, however, the excavations of Sir Leonard Woolley at Tell el-Muqayyar in southern Iraq identified an ancient Sumerian city called Urim or Uru.1 Woolley argued that this site was the location of Abraham’s Ur, not the traditional site in Turkey. Woolley’s argument has since gained widespread acceptance amongst biblical scholars.

While Woolley’s identification of Urim with the biblical Ur has remained popular, other scholars have challenged it. Chief among them has been Cyrus Gordon—a member of Woolley’s excavation team2—who disputed Woolley’s identification on linguistic and archaeological grounds.3 He and a vocal minority of scholars have argued for candidates in northern Syria and southern Turkey as being Abraham’s Ur.

An additional complication besides locating Abraham’s Ur is identifying the ancient “Chaldeans” or “Chaldees” mentioned in both the Book of Abraham and the book of Genesis. Our best current evidence suggests they were a nomadic Semitic tribe from modern Syria who emigrated into Mesopotamia and established a dynasty that came to power as the Babylonian Empire.4 The infamous biblical king Nebuchadnezzar was a descendant of these Chaldeans, and by his time the name Chaldean had become synonymous with Babylonian.5 Unfortunately, we have practically no inscriptional or archaeological evidence for the identity of the Chaldeans before they entered Mesopotamia long after Abraham’s lifetime. We therefore still have large gaps in the archaeological record that do not permit us to say much about the Chaldeans during Abraham’s lifetime.

Latter-day Saint scholars who have approached this question have pointed out that a northern Syrian-Turkish location for Ur is much more favorable for the Book of Abraham than a southern Mesopotamian location.6 For one thing, as mentioned, the Book of Abraham mentions some kind of Egyptian cultural influence or presence in and around Abraham’s homeland of Ur. Abraham’s kinsmen included “the god of Pharaoh” in their worship (along with a “priest of Pharaoh” to carry out the rituals), and practiced ritual human sacrifice “after the manner of the Egyptians” (Abraham 1:6–13). There is presently no evidence for Egyptian influence in southern Mesopotamia during the lifetime of Abraham (circa 2000–1,800 BC), but there is evidence for Egyptian influence in northern Syria at this time.

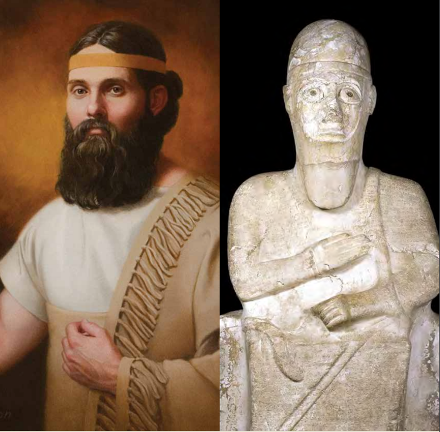

Additionally, the proximity of Abraham’s Ur to “the plain of Olishem” is an important geographical detail that works best in a northern as opposed to southern location. The Book of Abraham’s Olishem has been plausibly identified with the ancient city of Ulisum or Ulishum located somewhere in southern Turkey (although the precise location remains debated).7

Taken together, the evidence from the Book of Abraham text and external archaeological and inscriptional sources can reasonably point us in the general direction of modern northern Syria and Turkey as the ancient homeland of Abraham. While there are many questions that scholars still grapple with, enough evidence has surfaced over the years that paints a generally reliable picture of the historical and geographical world described in the Book of Abraham.

Further Reading

Stephen O. Smoot, “‘In the Land of the Chaldeans’: The Search for Abraham’s Homeland Revisited,” BYU Studies Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2017): 7–37.

Paul Y. Hoskisson, “Where Was Ur of the Chaldees?” in The Pearl of Great Price: Revelations from God, ed. H. Donl Peterson and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 119–36.

Footnotes

1 Leonard Woolley and Max Mallowan, Ur Excavations (London: The British Museum, 1927–62); Leonard Woolley, Ur of the Chaldees (London: E. Benn., 1929); Leonard Woolley, Abraham: Recent Discoveries and Hebrew Origins (London: Faber and Faber, 1936); Leonard Woolley, Excavations at Ur: A Record of Twelve Years’ Work (London: E. Benn. 1954); Leonard Woolley and P. R. S. Moorey, Ur “of the Chaldees,” rev. ed. (London: Herbert Press, 1982).

2 Cyrus H. Gordon, A Scholar’s Odyssey (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000), 35–36. Gordon was skeptical of Woolley’s efforts to “prove” the Bible was true for “well-heeled and God-fearing widows,” feeling that his efforts to link Abraham’s Ur with Tell el-Muqayyar compromised his otherwise “masterful” archaeological abilities.

3 Cyrus H. Gordon, “Abraham and the Merchants of Ura,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 17 (January 1958): 28–31; “Abraham of Ur,” in Hebrew and Semitic Studies, ed. D. Winton Thomas and W. D. McHardy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963), 77–84; “Where Is Abraham’s Ur?” Biblical Archaeology Review 3, no. 2 (1977): 20–21, 52; Cyrus H. Gordon, “Recovering Canaan and Ancient Israel,” in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, ed. Jack M. Sasson, 4 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1995), 4:2784.

4 A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), 160–63; Trevor Bryce, Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia (London: Routledge, 2009), 158.

5 Richard S. Hess, “Chaldea,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman, 6 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 1:886; Bryce, Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia, 159. But see also the cautionary note in Paul-Alain Beaulieu, “Arameans, Chaldeans, and Arabs in Cuneiform Sources from the Late Babylonian Period,” in Arameans, Chaldeans, and Arabs in Babylonia and Palestine in the First Millennium B.C., ed. A. Berlejung and M. P. Streck (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013), 33, 51, who points out that “relying solely on cuneiform sources from Babylonia, which are relatively abundant, we find no evidence that Nebuchadnezzar considered himself the ruler of Chaldeans and Arameans.” Instead, the Neo-Babylonian dynasty appears to have “adopted an archaizing political vocabulary which harked back to the time of the First Dynasty of Babylon and even to the Old Akkadian period. The perennial and unchanging nature of Babylonian civilization and its Sumero-Akkadian heritage was emphasized, and the reality of a society fragmented along ethnic, tribal, and linguistic lines, as well as by several other factors of social and institutional nature seems to be denied.”

6 John A. Tvedtnes and Ross Christensen, “Ur of the Chaldeans: Increasing Evidence on the Birthplace of Abraham and the Original Homeland of the Hebrews,” in Special Publications of the Society for Early Historic Archaeology (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1985); John M. Lundquist, “Was Abraham at Ebla? A Cultural Background of the Book of Abraham,” in Studies in Scripture—Volume Two: The Pearl of Great Price, ed. Robert L. Millet and Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City: Randall Book, 1985), 230–35; Paul Y. Hoskisson, “Where Was Ur of the Chaldees?” in The Pearl of Great Price: Revelations from God, ed. H. Donl Peterson and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1989), 127–31; Hugh Nibley, Abraham in Egypt, ed. Gary P. Gillum, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2000), 234–36, 238, 247; John Gee and Stephen D. Ricks, “Historical Plausibility: The Historicity of the Book of Abraham as a Case Study,” in Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 2001), 70–72; Hugh Nibley, An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2009), 418–28; John Gee, “Abraham and Idrimi,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 1 (2013): 34–39.

7 John Gee, “Has Olishem Been Discovered?” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 104–7.