Book of Abraham Insight #25

One way of determining whether the Book of Abraham is a translation of an underlying Egyptian document or if it was originally composed in English is to see if the text contains what might be called Egyptianisms, or literary and linguistic features of the Egyptian language. The presence of Egyptianisms in the text of the Book of Abraham “might indicate some knowledge of Egyptian on Joseph Smith’s part.”1 Because “Egyptian was not really understood in Joseph Smith’s day,”2 any knowledge of Egyptian Joseph Smith may have possessed could only have come by revelation.

A careful reading of the Book of Abraham does reveal some potential Egyptianisms in the English text. For example,

The earliest manuscript containing Abraham 1:17 reads “and this because their hearts are turned they have turned their hearts away from me.” The phrase “their hearts are turned” was crossed out and “they have turned their hearts” was written immediately afterwards. In Egyptian of the time period of the Joseph Smith Papyri the passive is expressed by the use of a third person plural. So the two phrases would be identical in Egyptian. The translator has to decide which way to render the passage.3

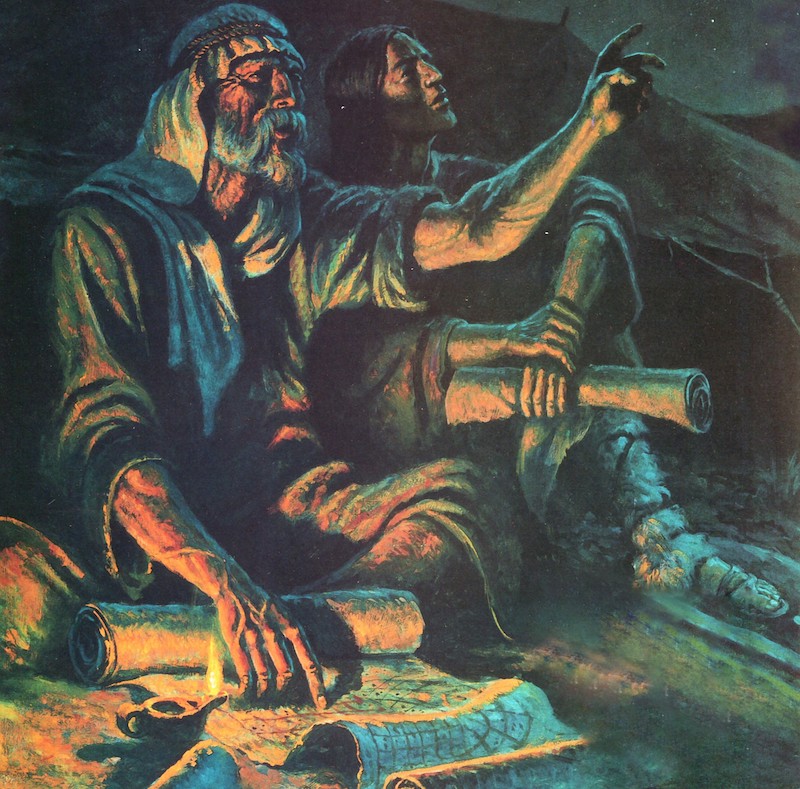

Another type of Egyptianism in the Book of Abraham is paronomasia or word play. Paronomasia is an attested feature of ancient Egyptian literature.4 In Abraham 3, the Lord showed Abraham a panoramic view of the cosmos and then a vision of the pre-mortal council in heaven.

The conversation between Abraham and the Lord shifts from a discussion of heavenly bodies to spiritual beings [halfway through the chapter]. This reflects a play on words that Egyptians often use between a star (ach) and a spirit (ich). The shift is done by means of a comparison: “Now, if there be two things, one above the other, and the moon be above the earth, then it may be that a planet or a star [ach] may exist above it; . . . as, also, if there be two spirits [ich], and one shall be more intelligent than the other” (Abraham 3:17–18). In an Egyptian context, the play on words would strengthen the parallel. . . . The Egyptian play on words between star and spirit allows the astronomical teachings to flow seamlessly into teachings about the preexistence which follow immediately thereafter.5

The question remains whether Abraham himself was responsible for these Egyptianisms or if they were the result of later scribes and copyists. Abraham appears to have been writing to a non-Egyptian audience (presumably his own descendants) and it is currently unknown what language he originally spoke.6 While Abraham taught the relationship between stars and spirits to the Egyptians and their own language would have supported paronomasia, it is possible that these Egyptianisms were introduced in the circa 300 BC copy of Abraham’s writings that were preserved on the papyri acquired by Joseph Smith. This, in turn, could potentially explain how Egyptianisms appear in a text written for Abraham’s Hebrew posterity.

While these Egyptianisms in the Book of Abraham do not indisputably prove that Joseph Smith was translating from ancient Egyptian, they are consistent with his claims to have done so.

Further Reading

John Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 427–448.

Footnotes

1 John Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 442.

2 Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” 443.

3 Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” 442.

4 See Siegfried Morenz, “Wortspiele in Ägypten,” in Festschrift Johannes Jahn zum 22. November 1957 (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann Verlag, 1957), 23–32; Antonio Loprieno, “Pun and Word Play in Ancient Egyptian,” in Puns and Pundits: Word Play in the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Literature, ed. Scott B. Noegel (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2000), 3–20; Penelope Wilson, Hieroglyphs: A Very Short Introduction (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003), 62–69; Barbara A. Richter, The Theology of Hathor of Dendera: Aural and Visual Scribal Techniques in the Per-Wer Sanctuary (Atlanta, GA: Lockwood Press, 2016), 13–19.

5 John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, 2017), 117, 119; cf. Silvia Zago, “Classifying the Duat: Tracing the Conceptualization of the Afterlife between Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts,” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache 145, no. 2 (2018): 212.

6 Eric Jay Olson, “I Have A Question,” Ensign, June 1982, 35–36.