Book of Abraham Insight #32

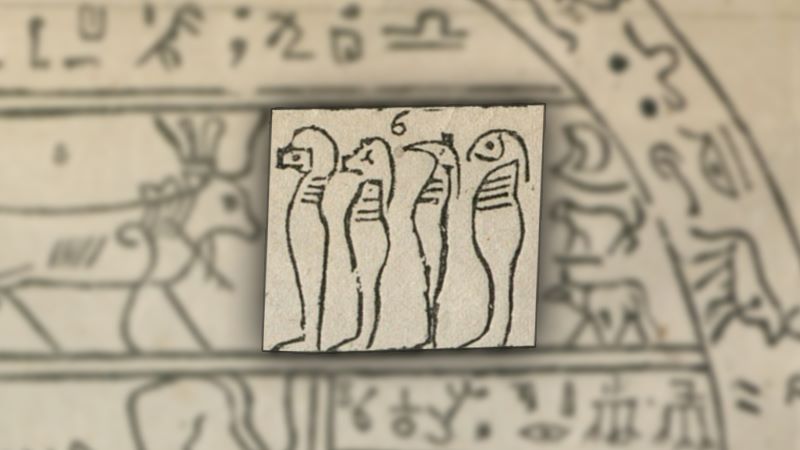

Figure 6 of Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham was interpreted straightforwardly by Joseph Smith as “represent[ing] this earth in its four quarters.”1 Based on contemporary nineteenth-century usage of this biblical idiom (Revelation 20:8), Joseph Smith evidently meant the figures represent the four cardinal points (north, east, south, and west).2 This interpretation finds ready support from the ancient Egyptians.

The four entities in Figure 6 represent the four sons of the god Horus: Hapi, Imsety, Duamutef, and Qebehsenuef.3 Over the span of millennia of Egyptian religion, these gods took on various forms as well as mythological roles and aspects.4 One such role was, indeed, as representing the four cardinal directions. “By virtue of its association with the cardinal directions,” observes one Egyptologist, “four is the most common symbol of ‘completeness’ in Egyptian numerological symbolism and ritual repetition.”5 As another Egyptologist has summarized,

The earliest reference to these four gods is found in the Pyramid Texts [ca. 2350–2100 BC] where they are said to be the children and also the “souls” of [the god] Horus. They are also called the “friends of the king” and assist the deceased monarch in ascending into the sky (PT 1278–79). The same gods were also known as the sons of Osiris and were later said to be members of the group called “the seven blessed ones” whose job was to protect the netherworld god’s coffin. Their afterlife mythology led to important roles in the funerary assemblage, particularly in association with the containers now traditionally called canopic jars in which the internal organs of the deceased were preserved. . . . The group may have been based on the symbolic completeness of the number four alone, but they are often given geographic associations and hence became a kind of “regional” group. . . . The four gods were sometimes depicted on the sides of the canopic chest and had specific symbolic orientations, with Imsety usually being aligned with the south, Hapy with the north, Duamutef with the east and Qebehsenuef with the west.6

This understanding is shared widely among Egyptologists today. James P. Allen, in his translation and commentary on the Pyramid Texts, simply identifies the four Sons of Horus as “representing the cardinal directions.”7 Manfred Lurker explains that “each [of the sons of Horus] had a characteristic head and was associated with one of the four cardinal points of the compass and one of the four ‘protective’ goddesses” associated therewith.8

Geraldine Pinch concurs, writing, “[The four Sons of Horus] were the traditional guardians of the four canopic jars used to hold mummified organs. Imsety generally protected the liver, Hapy the lungs, Duamutef the stomach, and Qebehsenuef the intestines. The four sons were also associated with the four directions (south, north, east, and west) and with the four vital components for survival after death: the heart, the ba, the ka, and the mummy.”9 “They were the gods of the four quarters of the earth,” remarks Michael D. Rhodes, “and later came to be regarded as presiding over the four cardinal points. They also were guardians of the viscera of the dead, and their images were carved on the four canopic jars into which the internal organs were placed.”10

Another Egyptologist, Maarten J. Raven, argues that the primary purpose of the Sons of Horus was to act as “the four corners of the universe and the four supports of heaven, and only secondarily with the protection of the body’s integrity.”11

The association of the Sons of Horus with the earth’s cardinal directions is explicit in one scene where, represented “as birds flying out to the four corners of the cosmos,” they herald the accession of king Rameses II to the throne.12

Imsety, go south that you may declare to the southern gods that Horus, [son of] Isis and Osiris, has assumed the crown and the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre [Ramesses II], has assumed the crown; Hapi, go north that you declare to the northern gods that Horus, [son of] Isis and Osiris, has assumed the crown and the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre [Ramesses II], has assumed the crown; Duamutef, go east that you may declare to the eastern gods that Horus, [son of] Isis and Osiris, has assumed the crown and the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre [Ramesses II], has assumed the crown; Qebehsenuef, go west that you may declare to the western gods that Horus, [son of] Isis and Horus, has assumed the crown and the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre [Ramesses II], has assumed the crown.13

While Joseph Smith’s succinct interpretation of Figure 6 in Facsimile 2 might have left out some additional details we know about the Sons of Horus (roles which evolved over the span of Egyptian religious history), it nevertheless converges nicely with current Egyptological knowledge.14

Further Reading

John Gee, “Notes on the Sons of Horus,” FARMS Report (1991).

Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2010), 299–302.

Footnotes

1 “A FAC-SIMILE FROM THE BOOK OF ABRAHAM, NO. 2.,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 16 (March 15, 1842): insert between pp. 720–721.

2 Thus George Stanley Faber, A General and Connected View of the Prophecies, Relative to the Conversion, Restoration, Union, and Future Glory of the Houses of Judah and Israel (London: F. C. and J. Rivington, 1808), 2:84, emphasis in original: “[N]ot merely from the north, but . . . from the east, the south, and the west, that is (in the language of St. John) from the four quarters of the earth.”; Robert Hodgson, The Works of the Right Reverend Beilby Porteus, D. D. Late Bishop of London (London: G. Sidney, 1811), 218: “[A]nd they shall gather together his elect (that is, shall collect disciples and converts to the faith) from the four winds, from the four quarters of the earth; or, as St. Luke expresses it, ‘from the east, and from the west, from the north, and from the south.’”; Matthew Henry, An Exposition of the Old and New Testament (London: Joseph Ogle Robinson, 1828), 3:1415: “As the city had four equal sides, answering to the four quarters of the world, east, west, north, and south; so in each side there were three gates, signifying that from all quarters of the earth there shall be some who shall get safe to heaven and be received there, and that there is a free entrance from one part of the world as from the other.”; Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York, NY: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. quarter: “A region in the hemisphere or great circle; primarily, one of the four cardinal points; as the four quarters of the globe; but used indifferently for any region or point of compass.”; William L. Roy, A New and Original Exposition on the Book of Revelation (New York, NY: D. Fanshaw, 1848), 13, emphasis in original. “Standing on (at) the four corners of the earth. They were placed as sentinels over the hostile armies, there to watch their movements, and prevent them from marching into Judea until the servants of God were sealed. Each of them had his particular station and duty assigned to him. One was stationed in the east, the other in the west, one in the north, and the other in the south.”; William Henry Scott, The Interpretation of the Apocalypse and Chief Prophetical Scriptures Connected With It (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1853), 185–186: “Rome is spoken of as overrunning and subduing the ‘whole earth,’ not merely in reference to the vast extent of her empire in point of territory, or the multitude of kingdoms which she absorded one after another, but properly and immediately because the four quarters of the earth, North, East, West, and South, are all incorporated by Rome into herself.”; Peter Canvan, “The Earth, As We Find It,” Saints’ Herald 20, no. 5 (March 1, 1873): 139: “And when the thousand years are expired, Satan shall be loosed out of his prison, and shall go out to deceive the nations which are in the four quarters of the earth. . . . The four corners may be represented by the north, south, east, west, which are the cardinal points.”

3 Michael D. Rhodes, “A Translation and Commentary of the Joseph Smith Hypocephalus,” BYU Studies 17, no. 3 (1977): 272–273; “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus . . . Twenty Years Later,” FARMS Report (1997), 11; Tamás Mekis, Hypocephali, PhD diss. (Eötvös Loránd University, 2013), 90, 96–97.

4 For an overview, see John Gee, “Notes on the Sons of Horus,” FARMS Report (1991).

5 Robert K. Ritner, The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice (Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute, 1993), 162n750.

6 Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 88.

7 James P. Allen, trans., The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, ed. Peter Der Manuelian (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005), 433.

8 Mafred Lurker, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 37–38.

9 Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002), 204.

10 Rhodes, “A Translation and Commentary of the Joseph Smith Hypocephalus,” 272–273.

11 Maarten J. Raven, “Egyptian Concepts on the Orientation of the Human Body,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 91 (2005): 52. As Raven elaborates, “Two conflicting orientation systems can be observed. The Sons of Horus can either occupy corner positions on coffins or canopic chests (Amset in the north-east, Hapy north-west, Duamutef south-east, and Qebehsenuef south-west; both pairs change places in the New Kingdom), or they are represented on the four side walls (Amset south, Hapy north, Duamutef east, and Qebehsenuef west). In the latter case, the corner positions are often taken by four protective goddesses. Obviously, the notions of the corners of the universe and of the four points of the compass were not clearly distinguished.”

12 Raven, “Egyptian Concepts on the Orientation of the Human Body,” 42. See also Hans Bonnet, Reallexikon der ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1952), 315; Matthieu Heerma van Voss, “Horuskinder,” in Lexikon der Ägyptologie, ed. Wolfgang Helck and Eberhard Otto (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1980), 3:53.

13 The Epigraphic Survey, Medinet Habu, Volume 4: Festival Scenes of Ramses III (Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press, 1940), Pl. 213; translation modified from Gee, Notes on the Sons of Horus, 60.

14 Hugh Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2010), 299–302; John Gee, “Hypocephali as Astronomical Documents,” in Aegyptus et Pannonia V: Acta Symposii anno 2008, ed. Hedvig Györy and Ádám Szabó (Budapest: The Ancient Egyptian Committee of the Hungarian-Egyptian Friendship Society, 2016), 66–67.