Book of Moses Essay #38

Moses 1:25-27

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock

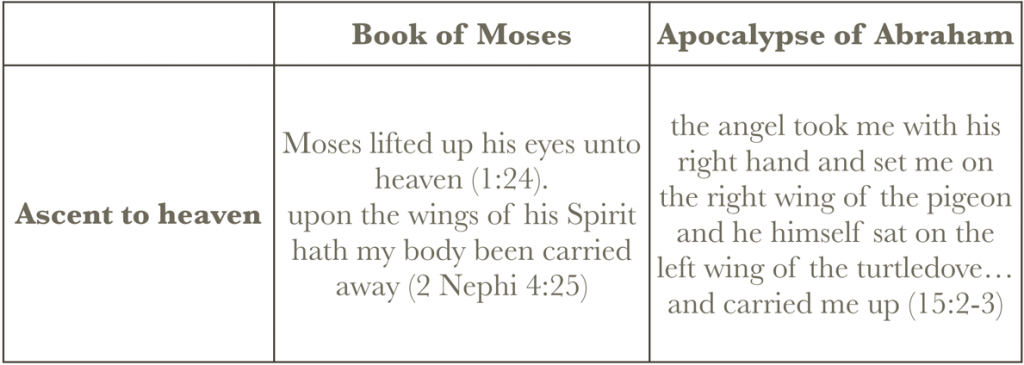

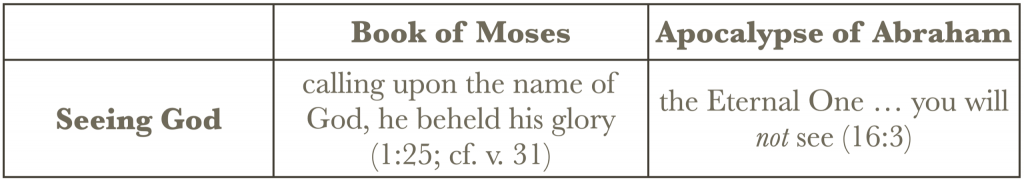

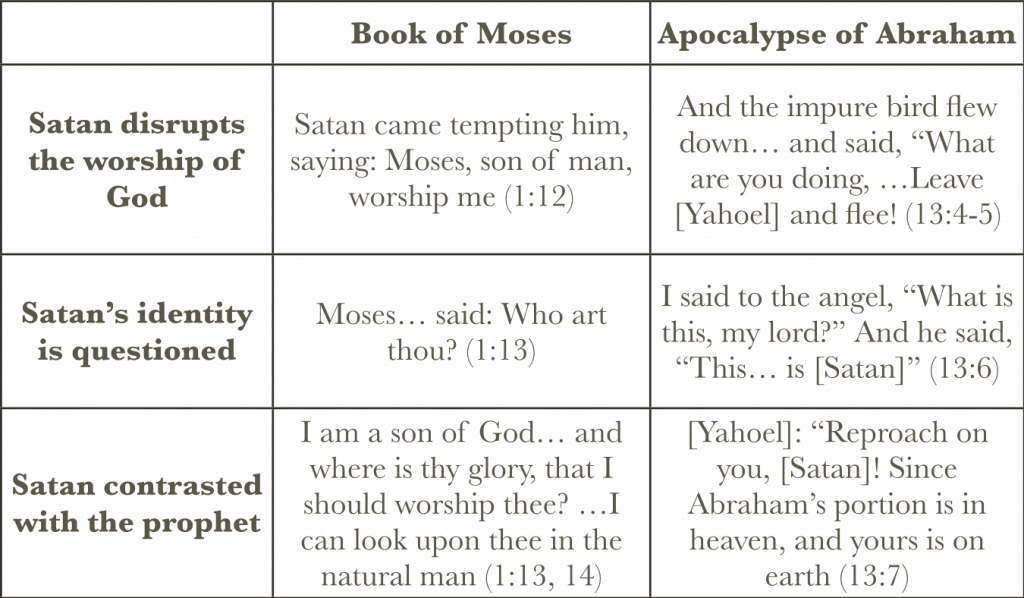

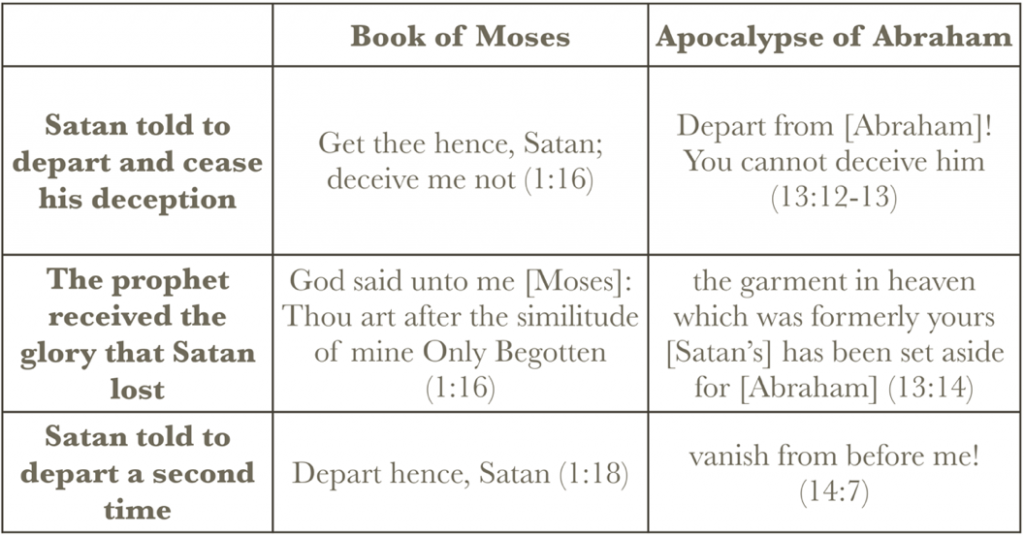

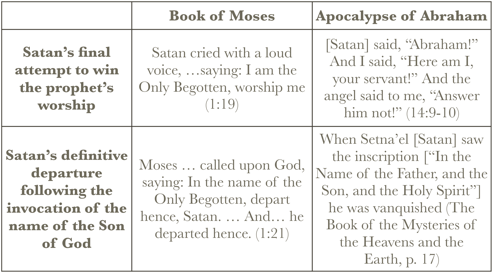

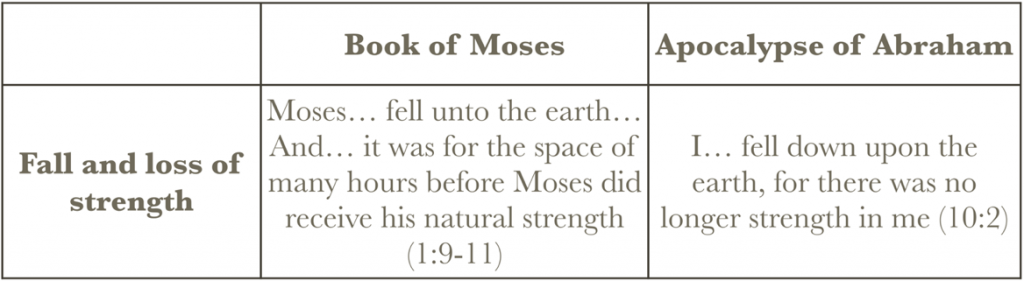

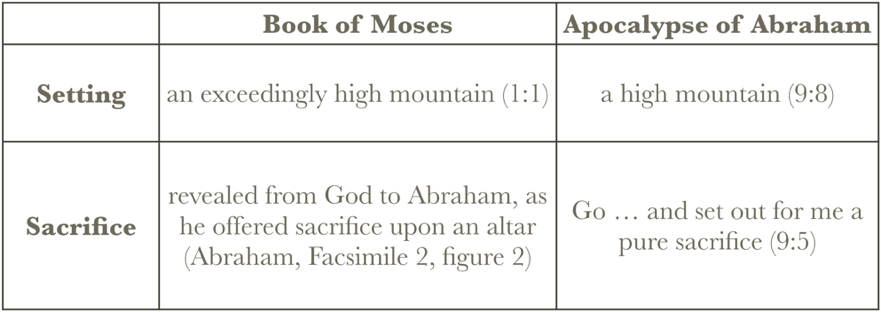

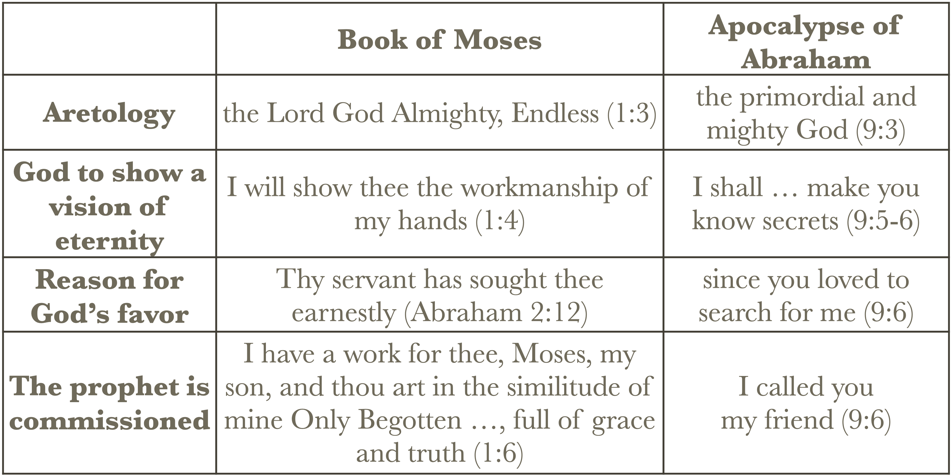

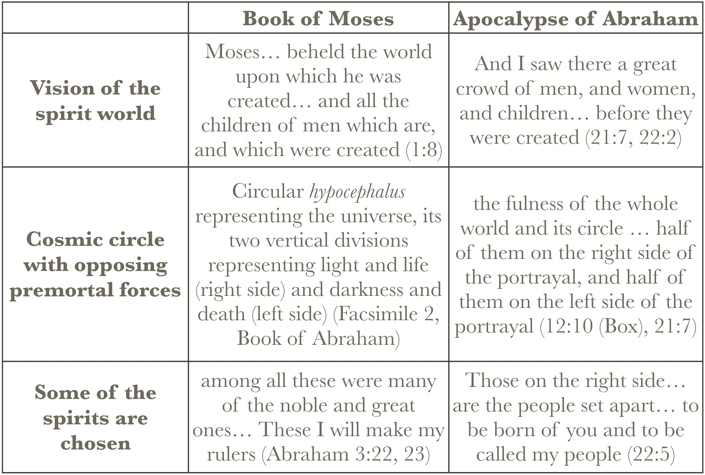

In light of our cultural and conceptual distance from the milieu of Moses 1, we are fortunate that imperfect documents from antiquity like the Apocalypse of Abraham (ApAb) may nevertheless provide keys for understanding that “mysterious other world,”1 even when existing manuscripts were written much later and, not infrequently, have come to us in a form that is riddled with the ridiculous.2 C.S. Lewis once addressed the potential of ancient sources, even those of poor quality, to inform modern scholars in surprising ways. He illustrated his point by saying:3

I would give a great deal to hear any ancient Athenian, even a stupid one, talking about Greek tragedy. He would know in his bones so much that we seek in vain. At any moment some chance phrase might, unknown to him, show us where modern scholarship had been on the wrong track for years.

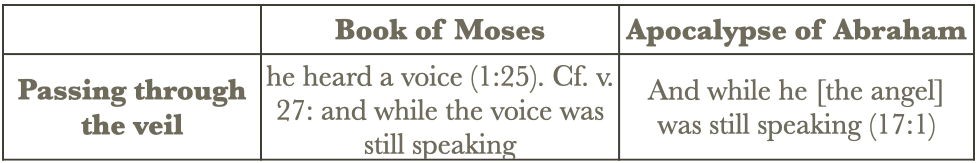

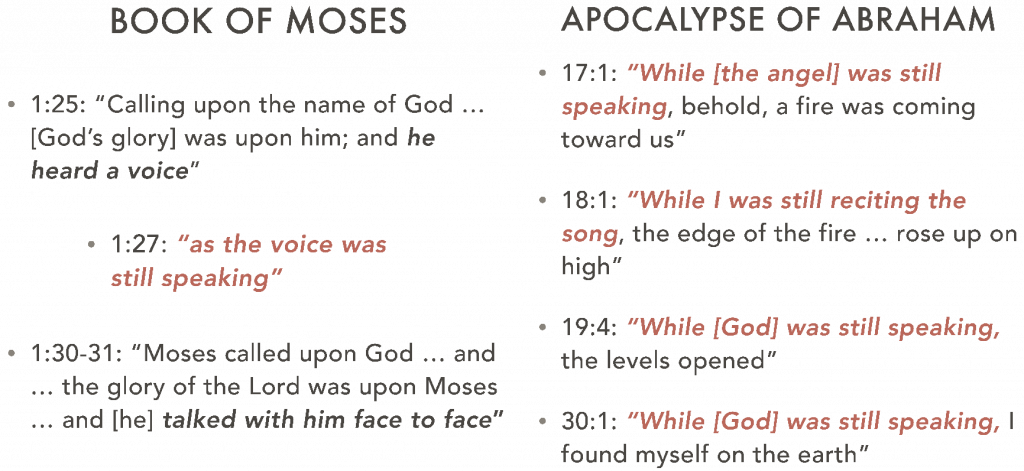

In a few instances, our experiences in comparing Moses 1 to ApAb have revealed the truth of Lewis’ claim. For example, as we looked carefully at Moses 1:27, a seemingly gratuitous and initially inexplicable phrase stood out: “as the voice was still speaking.”4 Surprisingly, we found that ApAb repeated similar phrases in analogous contexts.5 This discovery provided a welcome clue to a possible meaning of this enigmatic phrase in both Moses 1 and ApAb—a finding we will describe in more detail below.

Passing Through the Heavenly Veil: The Voice of God

In ApAb 17:3, the voice that accompanies Abraham’s passage through the veil is that of the angel Yaho’el. Yaho’el mediates God’s self-revelation to Abraham, as he previously mediated Abraham’s dialogue with Satan.6 Yaho’el, standing with the prophet in front of the veil, gives encouragement to a fearful Abraham, provides instructions to him, and promises to remain with him, “strengthening” him, as he comes into the presence of the Lord.7

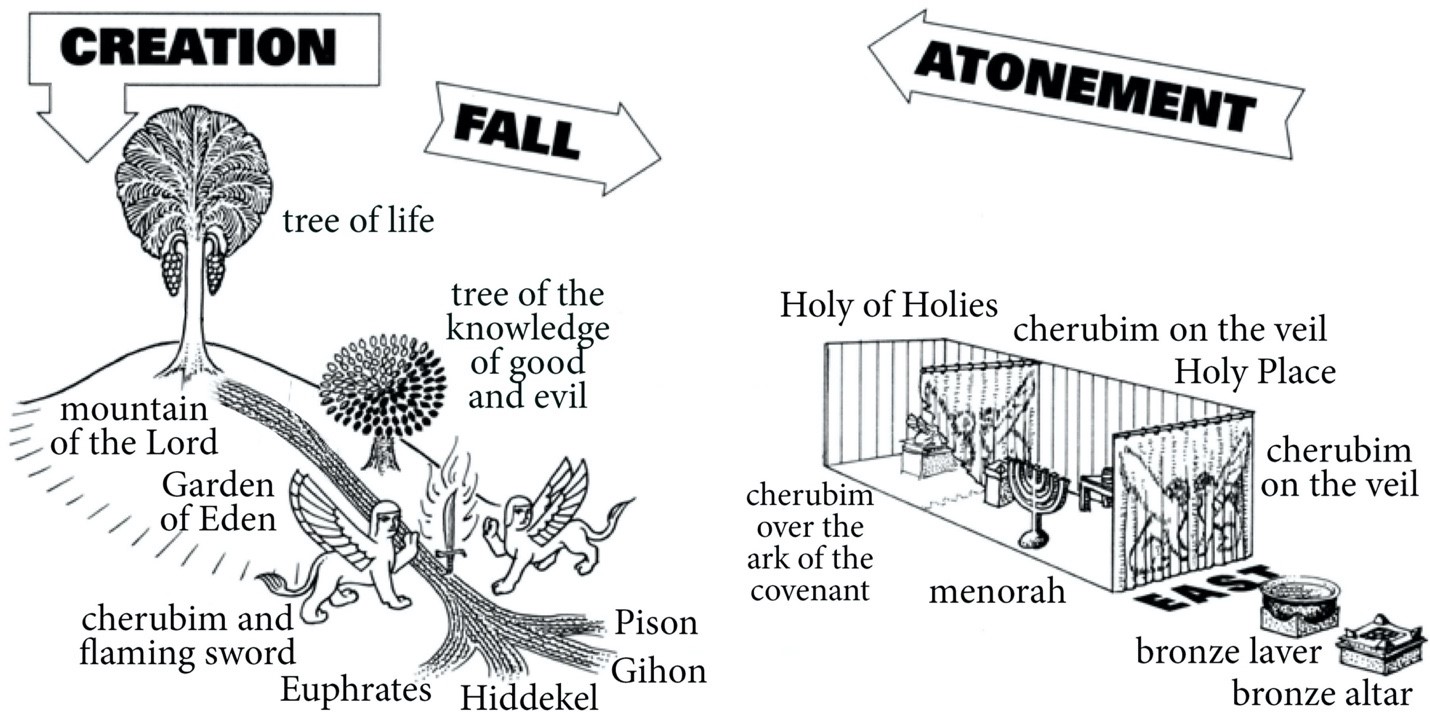

In contrast to ApAb’s account of mediated revelation, Moses experiences the voice of God directly. At first, Moses hears God’s voice but does not yet see Him “face to face.”8 His experience parallels that of Adam and Eve, when they also “called upon the name of the Lord” in sacred prayer.9 We read that “they heard the voice of the Lord from the way toward the Garden of Eden, speaking unto them, and they saw him not,10 for they were shut out from his presence.”11 The “way toward the Garden of Eden” is, of course, the path that terminates in “the way of the Tree of Life.”12 In the corresponding symbolism of the Garden of Eden and the temple, the Tree of Knowledge hides the Tree of Life, just as the veil hides the presence of God in His heavenly sanctuary.13 To proceed further, the veil must be opened to the petitioner.

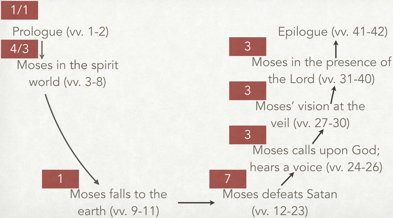

In Moses 1 and ApAb, multiple openings of various veils are signified explicitly, if somewhat cryptically. We observe that in Moses 1:25, a significant inclusio opens with a description of how, after “calling upon God,” the Lord’s glory “was upon” Moses “and he heard a voice.” In verses 30–31, the inclusio closes in similar fashion but states, significantly, that Moses sees God rather than just hearing Him: “Moses called upon God … the glory of the Lord was upon Moses so that Moses stood in the presence of God, and talked with him face to face.” Sandwiched between the opening and closing of the inclusio is a phrase that is intriguing because at first blush it seems both gratuitous and inexplicable: “as the voice was still speaking.”14

To our surprise, we discovered that ApAb repeats variants of a similar phrase (e.g., “And while he was still speaking.”15). Further examination of these instances revealed a commonality in each of the junctures where it is used. In short, in each of the four instances where this phrase appears in ApAb,16 —as in its single occurrence in Moses 1:27—the appearance of the phrase seems to be associated with an opening of a heavenly veil.17

In Moses 1, the phrase appears at the expected transition point in Moses’ ascent. We have already argued that when he “heard a voice” in v. 25, he was still positioned outside the veil. Immediately following the phrase “as the voice was still speaking,” he seems to have traversed the veil, allowing him to see every particle of the earth and its inhabitants projected on the inside of the veil. In this fashion, the veil serves in the Book of Moses as it typically does in similar accounts of heavenly ascent,18 namely as “a kind of ‘visionary screen.’”19 After the vision closes, Moses stands “in the presence of God” and talks with him “face to face.”20

We see a similar phenomenon repeated in ApAb. For example, the account explicitly describes how Abraham, after his upward ascent and while the angel “was still speaking,” looked down and saw a series of heavenly veils open beneath his feet, enabling his subsequent views of heavenly things.21 Moreover, as Abraham traverses the heavenly veil in a downward direction as part of his return to the earth, the expression “And while he was still speaking” recurs.22 Consistent with the change of glory that typically accompanies traversals of heavenly veils in such accounts, Abraham commented immediately afterward, “I found myself on the earth, and I said … I am no longer in the glory which I was above.”23

Passing Through the Heavenly Veil: The Voice of the Petitioner

In ancient literature, passage through the veil is frequently accompanied not only with the sorts of divine utterance just described but also with human speech. For example, instances of formal prayer24 and exchanges of words at the veil are variously described in Egyptian ritual texts,25 Jewish pseudepigrapha,26 and the Book of Mormon.27 Similarly, in ApAb, a recitation of a fixed set of words, often described as a “hymn,” “precedes a vision of the Throne of Glory.”28

In ApAb, Abraham is enjoined by the angel Yaho’el to recite a “hymn” in preparation for his ascent to receive a vision of the work of God.29 Significantly, Martha Himmelfarb observes that ApAb, unlike other pseudepigraphal accounts of heavenly ascent, “treats the [hymn] sung by the visionary as part of the means of achieving ascent.”30 Near the end of Abraham’s recitation, he implores God to accept the words of his prayer and the sacrifice that he has offered, to teach him, and to “make known to your servant as you have promised me.”31 Then, “while [he] was still reciting the [hymn],” the veil opens and the throne of glory appears to his view.32

Also of importance is that Abraham’s “form of ascension, where the literary protagonist reaches the highest sphere [of heaven] at once [rather than in stages] is only described in ApAb and cannot be found in any other apocalyptical text.”33 Thus, ApAb’s account of Abraham’s direct entry to the highest heaven without first traversing a set of lower heavens provides another unique resemblance to Moses 1.34

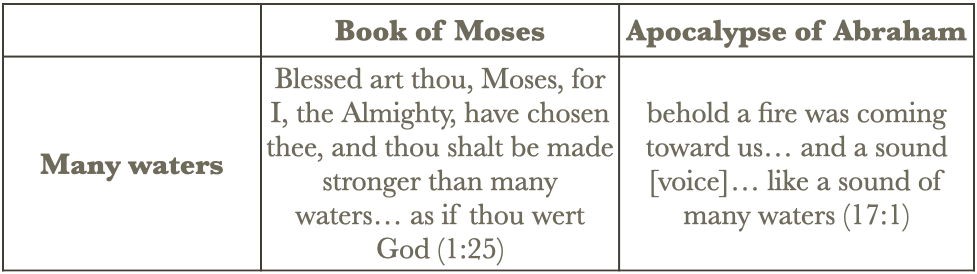

“Stronger Than Many Waters”

While both texts explicitly invoke the same concept of “many waters,” their contexts initially seem to be rather different. In Moses 1:25, the promise that Moses would be “made stronger than many waters” seems to relate most directly to the power he would be given to part the Red Sea, allowing his people to escape the advancing Egyptian army. As Moses communes through the veil, God enumerates specific promises to him, including the promise that he will “be made stronger than many waters; for they shall obey thy command as if thou wert God.”35

By way of contrast, in ApAb the “many waters” is part of several sensory images involved Abraham’s heavenly ascent. After Abraham traverses upward through a veil “while [the angel] was still speaking,” he sees “a fire” and hears a “sound [i.e., voice] … like a sound of many waters.”36 Though a “comparison with the tumult of an army camp is not drawn explicitly here [like it is in Ezekiel 1:24], one may recognize in the sound an allusion to the triumphant procession of a conqueror returning from war.”37 “The heavenly light is of dazzling brilliance, the divine voice is like thunder.”38 The resulting sensory-infused description announces to all the arrival of the Lord of Hosts in the fulness of His glory.

While the “many waters” images may seem at first glance to be unrelated, a connection becomes more apparent when the context of the Moses account is more fully understood. Rather than just signaling Moses’ future parting of the Red Sea and describing the godlike power that he will exercise in that and other regards, the imagery of “many waters” may evoke one of four symbolic names that ancient sources claim were given to Moses. These names seem to be ciphers for “keywords” related to temple worship, which would allow Moses to discover his past, present, and future destiny and eventually allow him to enter into God’s presence.

In the next Essay, we will discuss these names in more detail.

This article is adapted from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. “Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 38 (2020): 179-290.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 59–62.

———, David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. “Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 38 (2020): 179-290.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, p. 31.

Nibley, Hugh W. “To open the last dispensation: Moses chapter 1.” In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless: Classic Essays of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 1–20. Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1978, pp. 11–12.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, p. 220.

References

Alexander, Philip S. “3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Attridge, Harold W., and Helmut Koester, eds. Hebrews: A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews. Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible, ed. Frank Moore Cross, Klaus Baltzer, Paul D. Hanson, S. Dean McBride, Jr. and Roland E. Murphy. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1989.

Barker, Margaret. King of the Jews: Temple Theology in John’s Gospel. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2014.

Barney, Kevin L., ed. Footnotes to the New Testament for Latter-day Saints. 3 vols, 2007. http://feastupontheword.org/Site:NTFootnotes. (accessed February 26, 2008).

Bauckham, Richard, James R. Davila, Alex Panayotov, and James H. Charlesworth, eds. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. 2 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2013.

Block, Daniel I. The Book of Ezekiel: Chapters 25-48. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament, ed. Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1998.

Box, G. H. 1918. The Apocalypse of Abraham. Translations of Early Documents, Series 1: Palestinian Jewish Texts (Pre-Rabbinic). London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1919. https://www.marquette.edu/maqom/box.pdf. (accessed July 10, 2020).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?” BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4-49. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol49/iss1/2/.

———. “The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary.” In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013. https://rsc.byu.edu/ascending-mountain-lord/tree-knowledge-veil-sanctuary ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfIs9YKYrZE.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

———. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014. https://archive.org/download/150904TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses2014UpdatedEditionSReading ; http://www.templethemes.net/books/171219-SPA-TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses.pdf.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/details/151128TempleThemesInTheOathAndCovenantOfThePriesthood2014Update ; https://archive.org/details/140910TemasDelTemploEnElJuramentoYElConvenioDelSacerdocio2014UpdateSReading. (accessed November 29, 2020).

———. “Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent.” In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/faith-hope-and-charity-the-three-principal-rounds-of-the-ladder-of-heavenly-ascent/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ryan Dahle. “Could Joseph Smith have drawn on ancient manuscripts when he translated the story of Enoch? Recent updates on a persistent question (4 October 2019).” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 33 (2019): 305-73. www.templethemes.net. (accessed October 23, 2019).

Christian Symbols. In Fish Eaters. http://www.fisheaters.com/symbols.html. (accessed September 29, 2008).

Elkaïm-Sartre, Arlette, ed. Aggatdoth du Talmud de Babylone: La Source de Jacob – ‘Ein Yaakov. Collection “Les Dix Paroles”, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1982.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. All the Glory of Adam: Liturgical Anthropology in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Ginzberg, Louis, ed. The Legends of the Jews. 7 vols. Translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1909-1938. Reprint, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Goodenough, Erwin Ramsdell. Symbolism in the Dura Synagogue. 3 vols. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period 9-11, Bollingen Series 37. New York City, NY: Pantheon Books, 1964.

Gregory Nazianzen. ca. 350-363. “Oration 39: Oration on the Holy Lights.” In Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. 14 vols. Vol. 7, 351-59. New York City, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1894. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

Hanhart, Robert, and Alfred Rahlfs. 1935. Septuagint with Logos Morphology: Rahlfs Edition. Stuttgart, Germany: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1979.

Himmelfarb, Martha. Ascent to Heaven in Jewish and Christian Apocalypses. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Hyde, Orson. 1853. “The man to lead God’s people; overcoming; a pillar in the temple of God; angels’ visits; the earth (A discourse delivered by President Orson Hyde, at the General Conference held in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, October 6, 1853).” In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 1, 121-30. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. Hebrews: A Commentary. The New Testament Library, ed. C. Clifton Black and John T. Carroll. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006.

“Keys.” Nauvoo, IL: Times and Seasons 5:23, December 15, 1844, 748-49.

Kulik, Alexander. Retroverting Slavonic Pseudepigrapha: Toward the Original of the Apocalypse of Abraham. Text-Critical Studies 3, ed. James R. Adair, Jr. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004.

———. “Slavonic apocrypha and Slavic linguistics.” In The Old Testament Apocrypha in the Slavonic Tradition: Continuity and Diversity, edited by Christfried Böttrich, Lorenzo DiTommaso and Marina Swoboda Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism, 245-70. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2011. https://www.scribd.com/document/124601634/Article-Slavonic-Apocrypha-and-Slavic-Linguistics-1. (accessed December 3, 2019).

———. “Apocalypse of Abraham.” In Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, edited by Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel and Lawrence H. Schiffman. 3 vols. Vol. 2, 1453-81. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2013.

Lewis, C. S. 1955. “‘De Descriptione Temporum’.” In Selected Literary Essays, edited by Walter Hooper, 1-14. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Ludlow, Victor L. Isaiah: Prophet, Seer, and Poet. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1982.

Margalioth, Mordecai, ed. Midrash ha-Gadol ‘al hamishah humshey Torah: Sefer Bereshit. Jerusalem, Israel: Mosad ha-Rav Kook, 1947.

Mayerhofer, Kerstin. “‘And they will rejoice over me forever!’ The history of Israel in the light of the catastrophe of 70 C.E. in the Slavonic Apocalypse of Abraham.” Judaica Olomoucensia 1-2 (2014): 10-35. https://judaistika.upol.cz/fileadmin/userdata/FF/katedry/jud/judaica/Judaica_Olomucensia_2014_1-2.pdf. (accessed December 3, 2019).

Moffitt, David M. Atonement and the Logic of Resurrection in the Epistle to the Hebrews. Supplements to Novum Testamentum 141, ed. M. M. Mitchell and D. P. Moessner. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2011.

Mopsik, Charles, ed. Le Livre Hébreu d’Hénoch ou Livre des Palais. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1989.

Neusner, Jacob, ed. Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation. 3 vols. Vol. 2: Parashiyyot Thirty-Four through Sixty-Seven on Genesis 8:15-28:9. Brown Judaic Studies 105, ed. Jacob Neusner. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

———. 1978. “The early Christian prayer circle.” In Mormonism and Early Christianity, edited by Todd M. Compton and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 4, 45-99. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

———. 1993. “A house of glory.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 323-39. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

Origen. ca. 234-240. Homilies on Luke: Fragments on Luke. Translated by Joseph T. Lienhard. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1996.

Orlov, Andrei A. The Enoch-Metatron Tradition. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 107. Tübingen, Germany Mohr Siebeck, 2005.

Palmer, Richard E. The liminality of Hermes and the meaning of hermeneutics. In MacMurray College Faculty Writings. https://www.scribd.com/document/256305040/The-Liminality-of-Hermes-and-the-Meaning-of-Hermeneutics-Richard-Palmer. (accessed August 21, 2020).

Parry, Donald W., Jay A. Parry, and Tina M. Peterson, eds. Understanding Isaiah. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1998.

Philo. b. 20 BCE. “On drunkenness (De Ebrietate).” In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. 12 vols. Vol. 3. Translated by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. The Loeb Classical Library 247, ed. Jeffrey Henderson, 307-435. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930.

———. b. 20 BCE. “On the Virtues (De Virtutibus).” In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson. 12 vols. Vol. 8. Translated by F. H. Colson. The Loeb Classical Library 341, 158-305, 440-50. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1939.

Pietersma, Albert, and Benjamin G. Wright, eds. A New English Translation of the Septuagint and the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included Under That Title. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Romney, Marion G. “The oath and covenant which belongeth to the priesthood.” Conference Report, April 1962, 16-20.

Rona, Daniel. Israel Revealed: Discovering Mormon and Jewish Insights in the Holy Land. Sandy, UT: The Ensign Foundation, 2001.

Rubinkiewicz, Ryszard. “Apocalypse of Abraham.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 681-705. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

———. L’Apocalypse d’Abraham en vieux slave : Introduction, texte critique, traduction et commentaire. Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolikiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego, Zrodlai i monografie 129. Lublin, Poland: Société des Lettres et des Sciences de l’Université Catholique de Lublin, 1987.

Sandmel, Samuel, M. Jack Suggs, and Arnold J. Tkacik, eds. The New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Scholem, Gershom, ed. 1941. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. New York City, NY: Schocken Books, 1995.

Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Van Orden, Bruce A. We’ll Sing and We’ll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps. Provo, UT and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2018.

Vermes, Geza, ed. 1962. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English Revised ed. London, England: Penguin Books, 2004.

Weitzman, Steven. “The song of Abraham.” Hebrew Union College Annual 65 (1994): 21-33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23508527. (accessed September 6, 2015).

Witherington, Ben, III. Letters and Homilies for Jewish Christians: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Hebrews, James and Jude. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2007.

Notes on Figures

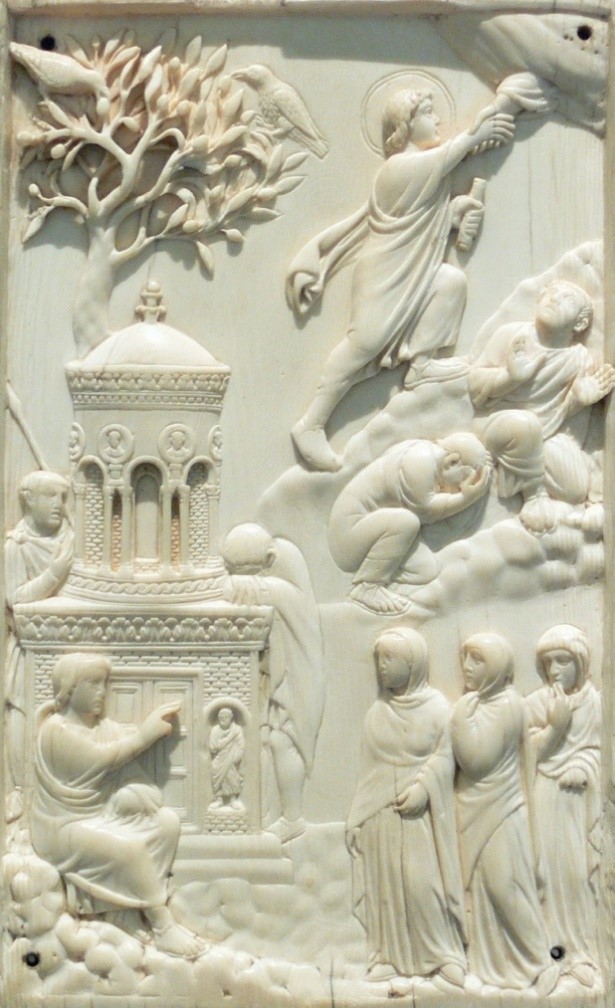

Figure 1. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reidersche_Tafel_c_400_AD.jpg (accessed June 22, 2020). In Hebrews 6:18‑20 Paul addresses as his audience all those who “have claimed his protection by grasping the hope set before us” (S. Sandmel, et al., New English Bible, Hebrews 6:18, p. 280). Continuing the description, he writes: “That hope we hold. It is like an anchor for our lives, an anchor safe and sure. It enters in through the veil, whose Jesus has entered on our behalf as a forerunner, having become a high priest forever after the order of Melchizedek” (S. Sandmel, et al., New English Bible, Hebrews 6:18–20, p. 280). Cf. Ether 12:4: “which hope cometh of faith, maketh an anchor to the souls of men, which would make them sure and steadfast.” See J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, pp. 97–100.

Alluding to the blessings of the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood (D&C 84:33–48. See also M. G. Romney, Oath, p. 17 and J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath), Paul wanted to assure the Saints of the firmness and unchangeableness of God’s promises symbolized in “grasp[ing] the hope set before [them]” (S. Sandmel, et al., New English Bible, Hebrews 6:18, p. 280). The “two irrevocable acts” that provide that firm assurance to disciples are “God’s promise and the oath by which He guarantees that promise” (K. L. Barney, NT Footnotes, 3:82; See also M. G. Romney, Oath, p. 17). By these verses, we are meant to understand that so long as we hold fast to the Redeemer, who has entered “through the veil on our behalf … as a forerunner,” we will remain firmly anchored to our heavenly home, and the eventual realization of the promise “that where I am, there ye may be also” (John 14:3. See also Hebrews 4:14; H. W. Attridge, et al., Hebrews, pp. 118–119).

Christian use of anchor imagery goes back at least to “the first century cemetery of St. Domitilla, the second and third century epitaphs of the catacombs” (Christian Symbols, Christian Symbols). Comparing the symbol of the anchor to an image in Virgil, Witherington concludes that he was “thinking no doubt of an iron anchor with two wings rather than an ancient stone anchor” (B. Witherington, III, Letters, p. 225). The shape of the anchor recalls God’s two assurances: the covenant itself and the oath by which the former is “made sure” (2 Peter 1:10). The symbol of the anchor evokes the tradition of pounding nails into the Western Wall of the Jerusalem Temple. Daniel Rona writes: “Older texts reveal a now forgotten custom of the ‘sure nails.’ This was the practice of bringing one’s sins, grief, or the tragedies of life to the remains of the temple wall and ‘nailing’ them in a sure place. The nails are a reminder of Isaiah’s prophecy [22:23–25] that man’s burden will be removed when the nail in the sure place is taken down” (D. Rona, Revealed, p. 194). Victor Ludlow concurs, concluding that “some of the terminology of [the wording in Isaiah 22:20–25] seems to refer to the priesthood keys and atoning powers of Jesus Christ” (V. L. Ludlow, Isaiah, p. 235. Cf. D. W. Parry, et al., Isaiah, p. 202). In an unsigned article in the Times and Seasons, probably written by William W. Phelps or John Taylor (see B. A. Van Orden, We’ll Sing, pp. 333-337), we read: “‘The nail fastened in a sure place,’ remains a mystery to the world, but the wise understand” (Keys, Keys, p. 748).

According to Margaret Barker, there is undoubtedly the sense in Hebrews 6:18–20 that “Jesus, the high priest, [stands] behind the veil in the Holy of Holies to assist those who [pass] through” (M. Barker, King of the Jews, pp. 42–43. Cf. 2 Nephi 9:41. See also Gregory Nazianzen, Oration 39, 7:358; Origen, Luke, p. 103; 1 Corinthians 3:13). According to Harold Attridge: “The anchor would thus constitute the link that ‘extends’ or ‘reaches’ to the safe harbor of the divine realms … providing a means of access by its entry into God’s presence” (H. W. Attridge, et al., Hebrews, p. 184; cf. pp. 185, 222–24. See also L. T. Johnson, Hebrews, pp. 172–73).

David Moffitt argues that just as Jesus was “exalted … above the entire created order—to the heavenly throne at God’s right hand,” so “humanity will be elevated to the pinnacle of the created order” (D. M. Moffitt, Atonement, pp. 300–3011). And just as the Son received “all the glory of Adam,” so “His followers will also inherit this promise if they endure … testing” (D. M. Moffitt, Atonement, p. 301).

The phrase “all the glory of Adam,” applied by Moffit to Jesus Christ and His followers, originated with the Jews in Qumran. See Rule of the Community (1QS), 4:22–26 in G. Vermes, Complete, p. 103. For a more detailed study of the meaning of this phrase in the context of the theology of the Qumran Community and of early Christians, see C. H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Glory.

Figures 2, 3, 5. Copyright Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

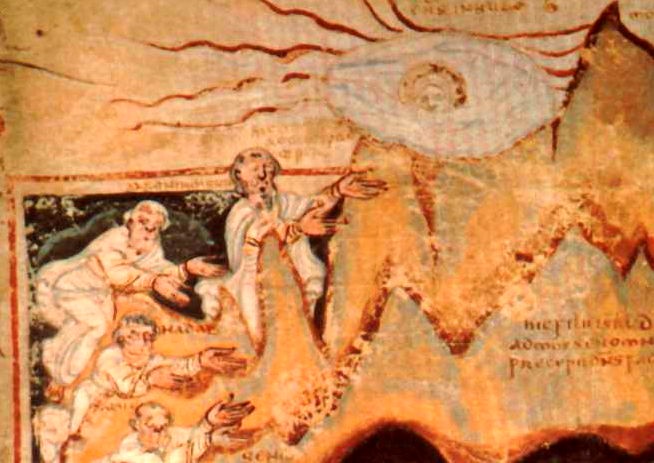

Figure 4. E. R. Goodenough, Dura Symbolism, 11, Plate V. Jewish tradition avers that “when the righteous see the Shekinah, they break straightway into song” (H. Schwartz, Tree, p. 341). Such “hymns” are often described as hymns of praise, emulating the Sanctus of the angels. For a broader overview of the function of hymns in later Jewish accounts of heavenly ascent in G. Scholem, Trends, pp. 57–63. For a discussion of the “tongue of angels” in 2 Nephi 31 and the hymn Moses sang during his heavenly ascent as recounted by Philo (Philo, Virtues, 72–78, pp. 207–209; cf. Deuteronomy 32:1–43) as illustrated in this mural (J. M. Bradshaw, Ezekiel Mural, pp. 17–19), see J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, pp. 103–104. See also The Inquiry of Abraham, in R. Bauckham, et al., Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, pp. 59–63.

Footnotes

1 As Richard Palmer observed (R. E. Palmer, Liminality):

Ancient texts are, for moderns, doubly alien: they are ancient and they are in another language. Their interpreter … is a bridge to somewhere else, he is a mediator between a mysterious other world and the clean, well-lighted, intelligible world in which “we live, and move, and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

2 For a summary of arguments and sources bearing on this question, see J. M. Bradshaw et al., Could Joseph Smith Have Drawn (2019), pp. 320–321.

3 C. S. Lewis, Descriptione, p. 13.

4 Moses 1:27.

5 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 17:1, p. 22; 18:1, p. 23; 19:4, p. 25; 30:1, p. 34.

6 Explaining the mediating function of the angel Metatron (who is sometimes identified with Yaho’el (A. Kulik, Apocalypse of Abraham, p. 1463 n. 10:3) and whose name is sometimes derived from the Latin mediator (ibid., p. 1663 n. 10:8)), Andrei Orlov writes (A. A. Orlov, Enoch-Metatron, p. 114 n. 125):

The inability of the angelic hosts to sustain the terrifying sound of God’s voice or the terrifying vision of God’s glorious Face is not a rare motif in the Hekhalot writings. In such depictions Metatron usually poses as the mediator par excellence who protects the angelic hosts participating in the heavenly liturgy against the dangers of direct encounter with the divine presence. This combination of the liturgical duties with the role of the Prince of the Presence appears to be a long-lasting tradition with its possible roots in Second Temple Judaism. James VanderKam notes that in 1QSb 4:25 the priest is compared with an angel of the Face.

7 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 16:2–4, p. 22. G. Scholem, Trends, p. 69 mentions the teaching in “a manuscript originating among the twelfth century Jewish mystics in Germany [Ms. British Museum, Margoliouth n. 752 f.; published in M. Margalioth, Midrash ha-Gadol] that Yaho’el was Abraham’s teacher and taught him the whole of the Torah. The same document also expressly mentions Yaho’el as the angel who—in [a] Talmudic passage [A. Elkaïm-Sartre, Ein Yaakov, Sanhédrin, 39a, p. 1031]—invites Moses to ascend to heaven.”

8 Moses 1:31. The opening inclusio in v. 25, corresponding to Moses 1:30, seems to be an “announcement of plot,” previewing what is going on generally in verses 25–31. What vv. 25–30 appear to emphasize is the voice in response to Moses’ calling upon the Lord as a prelude to the climactic encounter in v. 31.

9 Moses 5:4. For more on the nature of the prayer that is implied in this verse, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Commentary 5:4a, pp. 355–357; J. M. Bradshaw, Moses Temple Themes (2014), pp. 185–192.

10 Cf. “whom himself you will not see” (A. Kulik, Retroverting, 16:3, p. 22).

11 H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, 19, p. 233:

[Adam and Eve] could hear [God’s] voice speaking from the Garden, but they saw him not. They were shut out from his presence, but the link was there. This is what the rabbis call the bat ḳōl. The bat ḳōl is the “echo.” Literally, it means the “daughter of the voice.” After the last prophets, the rabbis didn’t get inspiration, but they did have the bat ḳōl. They could hear the voice. They could hear the echo. You could have inspiration, intuition, etc. (not face-to-face anymore, but the bat ḳōl).

12 Moses 4:31.

13 For more on this symbolic correspondence, see J. M. Bradshaw, Tree of Knowledge, pp. 52–54.

14 Moses 1:27.

15 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 17:1, p. 22; R. Rubinkiewicz, Apocalypse of Abraham, 17:1, p. 696.

16 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 17:1, p. 22; 18:1, p. 23; 19:4, p. 25; 30:1, p. 34. The first time the speaker is the angel Yaho’el (just before they bow and worship as the divine Presence approaches), the second time it is Abraham (reciting the “hymn” just prior to the vision of the seraphim), and in the last two instances God is the interlocutor (first, prior to Abraham’s vision of the firmaments, and then as Abraham descends again to earth).

17 Our search through the relevant literature revealed no commentary discussing this odd, repeated phrase in ApAb. However, from a sampling of contexts for the use of similar phraseology in the Old Testament (e.g., Genesis 24:15, 45: “before he/I had done speaking”; Job 1:16, 17, 18: “while he was yet speaking”; Daniel 7:20, 21: “whiles I was speaking”), it seems to indicate the immediacy of the subsequent action. In the Genesis and Job passages, it is a person who appears before the speech can conclude, while in Daniel, the words herald the coming of an angel.

The most relevant usage to the context in Moses 1 and ApAb is in the Septuagint version of Isaiah 58:9, which reads a little differently than in the Hebrew Bible to describe the immediacy of God’s appearance when a righteous individual petitions Him in the most perilous of circumstances by means of the most sacred form of prayer: “Then you shall cry out, and God will listen to you; while you are still speaking, he will say, ‘Here I am’” (A. Pietersma et al., Septuagint, Isaiah 58:9, p. 869). Greek: τότε βοήσῃ, καὶ ὁ θεὸς εἰσακούσεταί σου, ἔτι λαλοῦντός σου ἐρεῖ Ἰδοὺ πάρειμι (R. Hanhart et al., Septuagint, Isaiah 58:9, electronic edition). Citing the experience of Stephen, who saw the Lord “in the agonies of death,” Elder Orson Hyde taught (O. Hyde, 6 October 1853, p. 125):

True it is, that in the most trying hour, the servants of God may then be permitted to see their Father, and elder Brother. “But,” says one, “I wish to see the Father, and the Savior, and an angel now.” Before you can see the Father, and the Savior, or an angel, you have to be brought into close places in order to enjoy this manifestation. The fact is, your very life must be suspended on a thread, as it were. If you want to see your Savior, be willing to come to that point where no mortal arm can rescue, no earthly power save! When all other things fail, when everything else proves futile and fruitless, then perhaps your Savior and your Redeemer may appear; His arm is not shortened that He cannot save, nor His ear heavy that He cannot hear; and when help on all sides appears to fail, My arm shall save, My power shall rescue, and you shall hear My voice, saith the Lord.

18 E.g., P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch, 45:1, p. 296. Cf. 45:6, pp. 298–299.

19 A. Kulik, Apocalypse of Abraham, p. 1470 n. 21:2. Kulik notes that the “visionary screen” is called a “pargod`, ‘veil`,’ … in hekhalot literature.” For an extensive notes on the derivation and usage of this Persian loanword, see P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch, 45:1, p. 296 n. a; C. Mopsik, Hénoch, pp. 325–327 nn. 45:1–2.

20 Moses 1:31.

21 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 19:4-9, pp. 24-25; cf. Abraham 3:1–18.

22 Ibid., 30:1, p. 34; R. Rubinkiewicz, Apocalypse of Abraham, 30:1, p. 704.

23 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 30:1, p. 34; R. Rubinkiewicz, Apocalypse of Abraham, 30:1, p. 704.

24 Accounts purporting to reproduce the words of such prayers have long puzzled interpreters, principally because the introductions to such prayers or the prayers themselves are frequently portrayed as being given in unknown tongues. For example, during the ascent of ApAb, Abraham describes “a crowd of many people … shouting in a language the words of which I did not know” (A. Kulik, Retroverting, 15:6–7, p. 22; cf. A. Kulik, Apocalypse of Abraham, p. 1467 n. 15:7, probably referring to the special language of angels [A. Kulik, Slavonic Apocrypha and Slavic Linguistics, p. 252]). For more on this motif, see J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, pp. 102–104.

Repetition is another hallmark of solemn prayer. For example, at the dedication of the Kirtland temple the Prophet prayed following the pattern of “Adam’s prayer” (H. W. Nibley, House of Glory, p. 339) with threefold repetition: “O hear, O hear, O hear us, O Lord! … that we may mingle our voices with those bright, shining seraphs around thy throne” (D&C 109:78-79). Similarly in ApAb, Abraham, having “rebuilt the altar of Adam” at the command of an angel (H. W. Nibley, Prayer Circle, p. 57), is reported as having repeatedly raised his voice to God, saying: “El, El, El, El, Yaho’el … Accept my prayer” (cf. A. Kulik, Retroverting, 17:13, 20, p. 23). Kulik conjectures that “the fourfold repetition of the transliterated Hebrew ‘God’ might have come as a substitution for the four letters of God’s ineffable name [the Tetragrammaton]” [A. Kulik, Apocalypse of Abraham, p. 1467 n. 17:13]). Abraham’s prayer was also in imitation of Adam (“May the words of my mouth be acceptable” [L. Ginzberg, Legends, 1:91]; cf. Psalm 54:2: “Hear my prayer, O God; give ear to the words of my mouth”).

25 Compare H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), pp. 449-457.

26 See J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, pp. 103–104.

27 See ibid., p. 103.

28 A. Kulik, Apocalypse of Abraham, p. 1468 n. 18:1–14.

29 Drawing on Philo (Philo, Drunkenness, 105, p. 373) and Midrash Rabbah (J. Neusner, Genesis Rabbah 2, 43:9 C-E, p. 123), Steven Weitzman (S. Weitzman, Song of Abraham, pp. 27–33) argues that the Hymn of Abraham in ApAb 17 is an exegesis of Genesis 14:22–23. This reading interprets Abraham’s raised hand (Genesis 14:22) or perhaps the raise of both his hands (“he lifted up his right hand and his left hand to heaven” [J. Neusner, Genesis Rabbah 2, 43:9 C, p. 123]) prior to the opening of the veil to him as a prayer or “hymn” rather than as an oath.

30 M. Himmelfarb, Ascent to Heaven, p. 64, emphasis added.

31 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 17:20–21, p. 23.

32 Ibid., 18:1–3, pp. 23–24.

33 K. Mayerhofer, And They Will Rejoice, p. 28. Cf. M. Himmelfarb, Ascent to Heaven, p. 63. See also p. 137 n. 59.

34 Of course, it could be argued that Moses has implicitly ascended from the telestial world (where he encountered Satan) to the terrestrial world (where he called upon God in formal prayer) prior to his passage through the veil that defines the boundary of the celestial realm. Be that as it may, Moses’ upward journey, like Abraham’s upward journey, bears very little resemblance to the elaborately described passages through a series of lower heavens typically found in the extracanonical literature.

35 Moses 1:25.

36 A. Kulik, Retroverting, 17:1, p. 22. See similar imagery in Ezekiel 43:2; Revelation 1:15, 14:2, 19:6; D&C 133:22. Cf. Psalm 29:3; 2 Samuel 22:14. “The same terms are used in the ‘Greater Hekhaloth’ in describing the sound of the hymn of praise sung by the ‘throne of Glory’ to its King—‘like the voice of the waters in the rushing streams, like the waves of the ocean when the south wind sets them in uproar’” (G. Scholem, Trends, p. 61).

37 D. I. Block, Ezekiel 25-48, 43:1–2, 4, p. 579.

38 G. H. Box, Apocalypse, 17 n. 9, p. 36. Cf. 2 Enoch 39:7: “like great thunder with continual agitation of the clouds” (ibid., 17 n. 9, p. 36). See further discussion of this imagery in R. Rubinkiewicz, L’Apocalypse d’Abraham, pp. 155, 157 n. 1.