Book of Moses Essay #31

Moses 1

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

The Book of Moses as a Temple Text

Before delving directly into the text of Moses 1, we need to know more about what kind of a text we are dealing with. To set this chapter—as well as the remaining chapters in the Book of Moses—in their proper ancient and modern context, this Essay and the two that follow will treat these three topics:

· Heavenly Ascent and Ritual Ascent

· The Two-Part Pattern of Heavenly and Ritual Ascent

· Moses 1 as a “Missing” Prologue to Genesis

By the end of this sequence of three Essays,1 we hope to establish that the Book of Moses is a “temple text” from start to finish.2 By “temple text” we mean, in the words of John W. Welch, a document that “contains the most sacred teachings of the plan of salvation that are not to be shared indiscriminately, and that ordains or otherwise conveys divine powers through ceremonial or symbolic means, together with commandments received by sacred oaths that allow the recipient to stand ritually in the presence of God.”3

Within the Latter-day Saint temple endowment, a narrative relating to selected events of the primeval history provides the context for the presentation of divine laws and the making of covenants that are designed to bring mankind back into the presence of God.4 Because the Book of Moses is the most detailed account of the first chapters of human history found in Latter-day Saint scripture, it is already obvious to endowed members of the Church that the Book of Moses is a temple text par excellence, containing a pattern that interweaves sacred history with covenant-making themes.

What may be new to them, however, is that the temple themes in the Book of Moses extend beyond the first part of this story, which presents the Creation and the fall of Adam and Eve. There is also a part two of the temple story, which ends with the translation of Enoch and his city and the destruction of the wicked in Noah’s flood. We will show how these stories constitute fitting culminating episodes to the Book of Moses as a temple text. Moses 1 meaningfully acts as a prologue to the temple narrative, providing an account of Moses’ heavenly ascent and setting the context for the presentation of temple themes in the rest of the book.

Below, we will describe the similarities and differences between heavenly and ritual ascent, the two primary ways in which people participate in “temple-related” experiences. We will then give examples of heavenly and ritual ascent from the Jewish, Christian, Islamic, and Latter-day Saint traditions, demonstrating the widespread aspiration for such experiences across different religions and cultures throughout the ages.

Heavenly Ascent and Ritual Ascent

We begin this discussion with a statement about the central role that temple-related experiences have in God’s purposes for humankind—and, consequently, the reverence with which this subject must be approached. Scripture teaches that the greatest gift one can receive is that of eternal life:5 to be justified,6 sanctified,7 sealed,8 and raised to immortality with a resurrected celestial body to enter into the presence of God,9 knowing Him,10 receiving all that He has in connection with an eternal companion,11 having been bound with an eternal welding link to spouse, ancestors, and posterity through the authority and power of the priesthood,12 and becoming a son or daughter of our divine Father in the fullest sense of the word13 —all this made possible through “obedience to the laws and ordinances of the Gospel” and the Atonement of Jesus Christ.14

Individuals can enter the presence of God in one of two ways:

1. Literally, through heavenly ascent. In heavenly ascent, individuals may be transfigured temporarily to experience a vision of eternity,15 participate in worship and song with the angels,16 and have certain blessings conferred upon them that are “made sure”17 by the voice of God Himself. They may also, as an initiated member of the divine council,18 be commissioned to carry out a specific task, as is outlined with specific reference to Moses 1 in Stephen O. Smoot’s helpful exploration of this topic.19 In addition to exceptional accounts of heavenly ascent experienced by prophets in mortal life, all disciples of Jesus Christ look forward to an ultimate consummation of their aspirations by coming into the presence of the Father after death, thereafter dwelling in His presence for eternity.20

2. Ritually, through temple ordinances. As an example of one of these ordinances, which are administered under the authority of the Melchizedek priesthood, the Latter-day Saint endowment depicts a figurative journey that brings the worshipper step by step into the presence of God in His temple through narrative, symbolic actions, and covenant-making.21

The sequence of events described in accounts of heavenly ascent often resembles the same general pattern symbolized in temple ordinances, so that reading such accounts can help us make sense of temple rites. Conversely, temple rites help participants prepare for their own eventual entrance into the actual presence of God.22 No doubt the many scriptural allusions to temple-related symbols and ordinances in accounts of heavenly ascent serve as pearls of great price for attentive readers. In essence, heavenly ascent can be understood as the “completion or fulfillment” of the “types and images” of ritual ascent.23

President Russell M. Nelson has encouraged pondering and study of the rich symbolic teachings of the temple. Note that his suggestions for study encompass both passages where temple teachings are presented directly in discussions of fundamental doctrines and descriptions of ancient ritual ascent through temple worship as well as readings where temple teachings are described indirectly through the accounts of prophets such as Moses and Abraham who experienced heavenly ascent:

Spiritual preparation is enhanced by study. I like to recommend that members going to the temple for the first time read short explanatory paragraphs in the Bible Dictionary, listed under seven topics: “Anoint,” “Atonement,” “Christ,” “Covenant,” “Fall of Adam,” “Sacrifices,” and “Temple.”

One may also read in the Old Testament and the Books of Moses and Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price. Such a review of ancient scripture is even more enlightening after one is familiar with the temple endowment. Those books underscore the antiquity of temple work.24

Heavenly and Ritual Ascent in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Tradition

Jewish tradition. Some of the clearest examples of heavenly ascent are found in Old Testament accounts of the divine commission of prophets such as Moses, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel.25 In addition, many ancient accounts from the Second Temple period not included in the Bible document the heavenly ascents of figures such as Enoch26 and Abraham.27 Within the Book of Moses, the remarkable accounts of the heavenly ascents of Moses (Moses 1)28 and Enoch (Moses 6–7)29 provide detailed examples of the same genre.

As an example of the contrast between heavenly and ritual ascent in ancient Jewish tradition, Amy Elizabeth Paulsen-Reed compares the Apocalypse of Abraham, “where a man is taken up to heaven,” to the twelfth Sabbath song at Qumran, where the religious community joins the angels in praising God through ritual “while staying firmly on earth.”30 Latter-day Saints may have difficulty in connecting the complex system of sacrifices and laws of purity in the Old Testament to their own temple experience. However, they should be aware that a more complete version of Israelite temple ordinances than those in which most of the children of Israel participated was received by some kings, priests, and prophets in ancient times. These ordinances were part of the “order of Melchizedek.”31

In addition, some Jewish worshippers in the Second Temple period seem to have tried to emulate the exceptional prophetic figures who experienced heavenly ascent through participating in various forms of ritual ascent. For example, such practices have been documented in the synagogue of Dura Europos32 and at Qumran.33 Confirming President Nelson’s teaching that “temple patterns are as old as human life on earth”34 are accounts of temple worship throughout the ancient Near East35 —and elsewhere in the world36 —wherein endowed Latter-day Saints will find recognizable elements.

Christian tradition. Perhaps the most important authentic accounts of heavenly ascent in early Christianity, apart from the ascents of Jesus Christ Himself, relate to the experiences of Peter, James, and John on the Mount of Transfiguration. In an underappreciated Nauvoo discourse by Joseph Smith that has been reconstructed and annotated in detail elsewhere,37 the Prophet explained the meaning of this event for the early apostles and its significance for modern Latter-day Saints.

The early Christian theme of the “ladder of virtues,” a theme that builds on the symbolism of the experience of Jacob at Bethel and was expounded by Peter in connection with the events on the Mount of Transfiguration, describes a distinct progression of “stages in a Christian’s earthly experience.”38 The three stages that correlate to the temple-related attributes of faith, hope, and charity were described by Joseph Smith as the “three principal rounds”39 of a ladder of heavenly ascent. Each round marks a chief juncture in priesthood ordinances and on the pathway to eternal life. Among extant early Christian teachings on ritual ascent are the Lectures on the Ordinances (Mystagogikai Katecheseis) of Cyril,40 a fourth-century bishop in Jerusalem. According to Hugh Nibley, “these particular lectures contain ‘the fullest account extant’ of ordinances of the church at that crucial period.”41

Islamic tradition. Accounts of heavenly and ritual ascent are also to be found in Islam. The most well-known story of heavenly ascent concerns Muhammad himself.42 Doubting Meccans had asked that he “confirm the authenticity of his prophethood by ascending to heaven and there receiving a holy book. … In this, he was to conform to a model illustrated by many still extant legends … regarding Enoch, Moses, Daniel, Mani, and many other messengers who had risen to heaven, met God, and received from his right hand a book of scripture containing the revelation they were to proclaim.”43

During his “night journey” (isra), the angel Gabriel mounted him on Buraq, a winged steed, that “took him to the horizon” and then, in an instant, to the temple mount in Jerusalem.44 At the Gate of the Guard, Ishmael “asks Muhammad’s name and inquires whether he is indeed a true messenger.”45 After having given a satisfactory answer, Muhammad was permitted to gradually ascend from the depths of hell to the highest of the seven heavens on a golden ladder (mi’raj).46 At the gates of the Celestial Temple, a guardian angel again “ask[ed] who he [was]. Gabriel introduce[d] Muhammad, who [was] then allowed to enter the gardens of Paradise.”47

In addition, the events that make up the pilgrimage of Muslims to Mecca (hajj) can be seen as an example of ritual ascent.48 When the pilgrim successfully completes the final stage of his journey, “all veils are removed and he talks to the Lord without any veil between them.”49

Heavenly and Ritual Ascent among Latter-day Saints

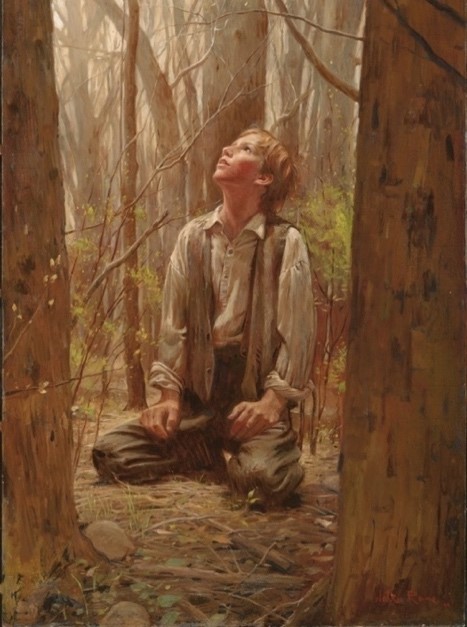

By 1830, Joseph Smith would have been familiar with several accounts of those who had seen God. For example, as a child he would have probably heard in nightly family Bible readings that “the Lord spake unto Moses face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend.”50 In his First Vision, he experienced a personal visit of the Father and the Son while yet a boy.51 Years later, when translating the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith learned of other prophets who had seen the Lord, including the detailed account of how the heavenly veil was removed for the brother of Jared so that he could come to know the premortal Jesus Christ on intimate terms.52

From the point of view of temple ritual and doctrine, as opposed to heavenly ascent, the Book of Mormon provided an important formative influence on Joseph Smith.53 Besides the temple-related information available in the published Book of Mormon, extant evidence relating to the lost pages from Mormon’s abridgement, carefully gathered and analyzed by Don Bradley, suggests many important clues about Nephite temples.54 Significantly, “rather than being a Levitical priesthood ‘after the order of Aaron,’ Nephite priesthood [and temple activities appear to have been] modeled primarily on Israelite royal priesthood ‘after the order of Melchizedek.’”55

However, of at least equal importance was the early tutoring on the temple received by the Prophet in 1830 and 1831 when he translated the early chapters of Genesis.56 The Joseph Smith Translation makes significant additions to Genesis, shedding new light on the priesthood, temple doctrines, and temple ordinances. It is significant that the Book of Moses, the first portion of his Genesis translation, was revealed more than a decade before he administered the full temple endowment to others in Nauvoo. Taken as a whole, the Book of Moses is one of several indicators that the Prophet Joseph Smith’s extensive knowledge of temple matters was the result of early revelations, not late inventions.57

Having briefly explored in this article the nature of heavenly and ritual ascent, the next Essay58 will describe the distinctive two-part pattern that characterizes accounts of such ascents—both anciently and in the Book of Moses.

This article is adapted and updated from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “What did Joseph Smith know about modern temple ordinances by 1836?” In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 1–144. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016, pp. 2–3.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. “The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East.” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1–42.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014, pp. 23–29.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. “Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 38 (2020): 179-290.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 18–19.

Hamblin, William J. “Temple motifs in Jewish mysticism.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 440–476. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Nelson, Russell M. Perfection Pending. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1998, pp. 3–11.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 461–532.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, pp. 193–194, 204.

Parry, Jay A., and Donald W. Parry. “The temple in heaven: Its description and significance.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 515–532. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Ricks, Stephen D., and John J. Sroka. “King, coronation, and temple: Enthronement ceremonies in history.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 236–271. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

References

Alexander, Philip S. “3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Ashraf, Syed Ali. “The inner meaning of the Islamic rites: Prayer, pilgrimage, fasting, jihad.” In Islamic Spirituality 1: Foundations, edited by Seyyed Hossein Nasr, 111-30. New York City, NY: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1987.

Barker, Margaret. “Isaiah.” In Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, edited by James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson, 489-542. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

———. Temple Theology. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2004.

Bradley, Don. “Acquiring an All-Seeing Eye: Joseph Smith’s First Vision as Seer Initiation and Ritual Apotheosis, 19 July 2010, cited with permission.”

———. “Joseph Smith’s First Vision as Endowment and Epitome of the Gospel of Jesus Christ (or Why I Came Back to the Church).” Presented at the FairMormon Conference, August 7-9, 2019. https://www.fairmormon.org/conference/august-2019. (accessed August 19, 2019).

———. The Lost 116 Pages: Reconsructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2019.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?” BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4-49. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol49/iss1/2/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. “The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East.” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol4/iss1/1/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/details/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

———. “The LDS book of Enoch as the culminating story of a temple text.” BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 39-73. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/140224-a-Bradshaw.pdf. (accessed September 19, 2017).

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/details/151128TempleThemesInTheOathAndCovenantOfThePriesthood2014Update.

———. “Now that we have the words of Joseph Smith, how shall we begin to understand them? Illustrations of selected challenges within the 21 May 1843 Discourse on 2 Peter 1.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 20 (2016): 47-150. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/now-that-we-have-the-words-of-joseph-smith-how-shall-we-begin-to-understand-them/.

———. “What did Joseph Smith know about modern temple ordinances by 1836?”.” In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 1-144. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. http://www.jeffreymbradshaw.net/templethemes/publications/01-Bradshaw-TMZ%203.pdf.

———. “Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent.” In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/faith-hope-and-charity-the-three-principal-rounds-of-the-ladder-of-heavenly-ascent/.

———. 2018. How Might We Interpret the Dense Temple-Related Symbolism of the Prophet’s Heavenly Vision in Isaiah 6? In Interpreter Foundation Old Testament KnoWhy JBOTL36A. https://interpreterfoundation.org/knowhy-otl36a-how-might-we-interpret-the-dense-temple-related-symbolism-of-the-prophet-s-heavenly-vision-in-isaiah-6/. (accessed November 23, 2018).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. ““By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified”: The Symbolic, Salvific, Interrelated, Additive, Retrospective, and Anticipatory Nature of the Ordinances of Spiritual Rebirth in John 3 and Moses 6.” In Sacred Time, Sacred Space, and Sacred Meaning (Proceedings of the Third Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 5 November 2016), edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. The Temple on Mount Zion 4, 43-237. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2020. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/Bradshaw%20and%20Bowen-By%20the%20Blood-from%20TMZ4%20(2016).pdf.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. “Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 179-290. https://journal.

Cyril of Jerusalem. ca. 347. “Five Catechetical Lectures to the Newly Baptized on the Mysteries.” In Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. 14 vols. Vol. 7, 144-57. New York City, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1894. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994.

Dyer, Alvin R. The Meaning of Truth. Revised ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1970.

Ehat, Andrew F. “‘Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord?’ Sesquicentennial reflections of a sacred day: 4 May 1842.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 48-62. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. First Corinthians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Yale Bible. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. All the Glory of Adam: Liturgical Anthropology in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Hamblin, William J., and David Rolph Seely. Solomon’s Temple: Myth and History. London, England: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Hundley, Michael B. Gods in Dwellings: Temples and the Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013.

Ibn Ishaq ibn Yasar, Muhammad. d. 767. The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah. Translated by Alfred Guillaume. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Isenberg, Wesley W. “The Gospel of Philip (II, 3).” In The Nag Hammadi Library, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 139-60. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Lambert, Neal E., and R. Cracroft. “Literary form and historical understanding: Joseph Smith’s First Vision.” Journal of Mormon History 7 (1980): 33-42.

Latter-day Saint Bible Dictionary. In Latter-day Saint Scriptures. https://www.lds.org/scriptures/bd/prayer?lang=eng. (accessed February 28, 2018).

Lundquist, John M. The Temple: Meeting Place of Heaven and Earth. London, England: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Madsen, Truman G. 1978. “House of glory.” In Five Classics by Truman G. Madsen, 273-85. Salt Lake City, UT: Eagle Gate, 2001. Reprint, Madsen, Truman G. 1978. “House of glory.” In The Temple: Where Heaven Meets Earth, 1-14. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

Magness, Jodi. “Heaven on earth: Helios and the zodiac cycle in ancient Palestinian synagogues.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59 (2005): 1-52.

McConkie, Bruce R. Mormon Doctrine. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Nelson, Russell M. Perfection Pending. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1998.

———. Teachings of Russell M. Nelson. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2018.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1967. “Apocryphal writings and the teachings of the Dead Sea Scrolls.” In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 264-335. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992.

———. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam, eds. 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 37-82. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012.

Paulsen-Reed, Amy Elizabeth. The Origins of the Apocalypse of Abraham (Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Theology in the subject of the Hebrew Bible). Harvard Divinity School. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2016. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:27194248. (accessed August 4, 2019).

Peterson, Daniel C. “Muhammad.” In The Rivers of Paradise: Moses, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Muhammad as Religious Founders, edited by David Noel Freedman and Michael J. McClymond, 457-612. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001.

Ragavan, Deena, ed. Heaven on Earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic Symbolism in the Ancient World. Papers from the Oriental Institute Seminar ‘Heaven on Earth’ held at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2-3 March 2012. Oriental Institute Seminars 9. Chicago, IL: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2013.

Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions. Monographs of the Hebrew Union College 14. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992.

Reeves, John C., and Annette Yoshiko Reed. Sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. 2 vols. Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages 1. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Schimmel, Annemarie. 1981. And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety. English ed. Studies in Religion, ed. Charles H. Long. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Smith, Gerald E. Schooling the Prophet: How the Book of Mormon influenced Joseph Smith and the early Restoration. Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2015.

Smith, Joseph Fielding, Jr. 1931. The Way to Perfection: Short Discourses on Gospel Themes Dedicated to All Who Are Interested in the Redemption of the Living and the Dead. 5th ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Genealogical Society of Utah, 1945.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Smoot, Stephen O. 2012. ‘I am a son of God’: Moses’ ascension into the divine council. In 2012 BYU Religious Education Student Symposium. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/byu-religious-education-student-symposium-2012/i-am-son-god-moses-ascension-divine-council. (accessed September 29, 2018).

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. The Book of Giants from Qumran: Texts, Translation, and Commentary. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Talmage, James E. The House of the Lord. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1971.

Thomas, M. Catherine. “The Brother of Jared at the veil.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 388-98. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Welch, John W. “The temple in the Book of Mormon: The temples at the cities of Nephi, Zarahemla, and Bountiful.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 297-387. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. With permission from the artist. Published with the title of “Moses: Deliverer and Lawgiver” in Ensign, April 2006, http://lds.org/ensign/2006/04/moses-deliverer-and-law-giver?lang=eng.

Figure 2. Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece. Licensed from Alamy.com. Image ID: BM2KC6.

Figure 3. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Detail of image published in W. J. Hamblin, et al., Temple, p. 136 figure 134.

Figure 4. http://www.deseretnews.com/top/704/1/The-Brother-of-Jared-Sees-the-Finger-of-the-Lord-Arnold-Fribergs-religious-paintings.html (accessed 21 June 2016).

Figure 5. http://www.walterraneprints.com/prints/the-desires-of-my-heart. By permission of the artist, with special thanks to Linda Rane.

Footnotes

1 Essays #31–33.

2 For a discussion of “temple theology” that highlights the similarities and differences of the Latter-day Saint position on the subject and describes how the Book of Moses functions as a “temple text,” see J. M. Bradshaw, LDS Book of Enoch, pp. 39–44. The term “temple theology” has its roots in the writings of Margaret Barker (see M. Barker, Temple Theology for a convenient summary of her voluminous writings on the subject). Over the course of decades, she has argued that Christianity arose not as a strange aberration of the Judaism of Jesus’ time but rather as a legitimate heir of the theology and ordinances of Solomon’s Temple. The loss of much of the original Jewish temple tradition would have been part of a deliberate program by later kings and religious leaders to undermine the earlier teachings. To accomplish these goals, some writings previously considered to be scripture are thought to have been suppressed and some of those that remained are thought to have been changed to be consistent with a different brand of orthodoxy. While scholars differ in their understanding of details about the nature and extent of these changes and how and when they might have taken place, most agree that essential light can be shed on questions about the origins and beliefs of Judaism and Christianity by focusing on the recovery of early temple teachings and on the extracanonical writings that, in some cases, seem to preserve them.

3 J. W. Welch, Temple in the Book of Mormon, pp. 300–301.

4 J. E. Talmage, House of the Lord (1971), pp. 83–84.

5 See Doctrine and Covenants 14:7. President Russell M. Nelson has stressed (R. M. Nelson, Teachings, May 2001, p. 363):

Eternal life is more than immortality. Eternal life is exaltation in the highest heaven—the kind of life that God lives.

6 See Doctrine and Covenants 20:30; Moses 6:60; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, p. 21; J. M. Bradshaw et al., By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified (TMZ 4), pp. 84–92.

7 See Doctrine and Covenants 20:31; 84:33; Moses 6:60; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 21–32; J. M. Bradshaw et al., By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified (TMZ 4), pp. 84–103.

8 See, e.g., Doctrine and Covenants 88:4; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 45–51, 58–65, 81–84, 97–98, 108–109, 114, 149, 158, 166, 172–176, 182–186, 189–194; J. M. Bradshaw et al., By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified (TMZ 4), pp. 56–57, 88, 95–96, 100, 195–197, 204–205, 211–212; J. M. Bradshaw, Now That We Have the Words.

9 See, e.g., Doctrine and Covenants 76:64–70; 84:33; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 28–29.

10 See, e.g., John 17:3; Doctrine and Covenants 84:47; 93:1; 132:24; ibid., pp. 78–79.

11 See, e.g., Doctrine and Covenants 76:55, 59; 84:38; 131:1–4; ibid., pp. 109, 219.

12 See Doctrine and Covenants 128:17–18. President Russell M. Nelson has said (R. M. Nelson, Teachings, 29 April 2006, 114):

There is spiritual safety in the circle of the family—the basic unit of society. The family is a sacred institution. The Gospel was restored to the earth and the Church exists to exalt the family. The earth was created that each premortal spirit child of God might have hits mortal experience, gain a physical body, choose a companion, form a family, and have that family sealed eternally in a temple of the Lord. If it were not so, the whole earth would be utterly wasted. Scriptures stress that doctrine time and time again (see Doctrine and Covenants 2:3; 138:48).

13 See, e.g., Doctrine and Covenants 76:58; J. M. Bradshaw et al., By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified (TMZ 4), pp. 56–57; 92, 99–103.

14 See, e.g., Articles of Faith 1:3.

15 E.g., P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch, 1:9–12, pp. 256–257.

16 E.g., ibid., 45, pp. 296–299.

17 2 Peter 1:10. See J. M. Bradshaw, Now That We Have the Words; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 59–65.

18 See M. Barker, Isaiah, p. 504; J. M. Bradshaw, How Might We Interpret.

19 See S. O. Smoot, I Am a Son of God for a discussion of the divine council in relation to Moses 1.

20 President Nelson has taught (R. M. Nelson, Perfection Pending, pp. 6–7, 9):

Resurrection is requisite for eternal perfection. Thanks to the atonement of Jesus Christ, our bodies, corruptible in mortality, will become incorruptible. Our physical frames, now subject to disease, death, and decay, will acquire immortal glory (see Alma 11:45; Doctrine and Covenants 76:64–70). Presently sustained by the blood of life (see Leviticus 17:11) and ever aging, our bodies will be sustained by spirit and become changeless and beyond the bounds of death (Latter-day Saint Bible Dictionary, Latter-day Saint Bible Dictionary, Resurrection, p. 761: “A resurrection means to become immortal, without blood, yet with a body of flesh and bone”).

Eternal perfection is reserved for those who overcome all things and inherit the fulness of the Father in His heavenly mansions. Perfection consists in gaining eternal life—the kind of life that God lives (see J. F. Smith, Jr., Way 1945, p 331; B. R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, p. 237). …

Perfection is pending. It can come in full only after the Resurrection and only through the Lord. It awaits all who love Him and keep His commandments. It includes thrones, kingdoms, principalities, powers, and dominions (see Doctrine and Covenants 132:19). It is the end for which we are to endure (see Matthew 10:22; 24:13; Mark 13:13). It is the eternal perfection that God has in store for each of us.

21 J. E. Talmage, House of the Lord (1971), pp. 159–161. Cf. the words of Oliver Cowdery, editor of The Evening and Morning Star, who wrote the following description in 1834 (see The Elders of the Church in Kirtland to Their Brethren Abroad, Evening and Morning Star, 2:17, February 1834, p. 135. This passage is sometimes mistakenly attributed to Joseph Smith [see A. F. Ehat, Who Shall Ascend, p. 62 n. 11]—see J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 22 January 1834, p. 51):

We consider that God has created man with a mind capable of instruction, and a faculty which may be enlarged in proportion to the heed and diligence given to the light communicated from heaven to the intellect; and that the nearer man approaches perfection, the more conspicuous are his views, and the greater his enjoyments, until he has overcome the evils of this life and lost every desire of sin; and like the ancients, arrives to that point of faith that he is wrapped in the glory and power of his Maker and is caught up to dwell with Him. But we consider that this is a station to which no man has ever arrived in a moment: he must have been instructed in the government and laws of that kingdom by proper degrees, till his mind was capable in some measure of comprehending the propriety, justice, equity, and consistency of the same.

President David O. McKay made the following statement (as remembered in T. G. Madsen, House, p. 282):

I believe there are few, even temple workers, who comprehend the full meaning and power of the temple endowment. Seen for what it is, it is the step-by-step ascent into the Eternal Presence. If our young people could but glimpse it, it would be the most powerful spiritual motivation of their lives.

President Russell M. Nelson has said (R. M. Nelson, Teachings, 5 June 1997, pp. 371–372):

In [the] temple there is a symbolic pathway of progression. The baptismal font is located in the lowest part of the temple, symbolizing the fact that Jesus was baptized in the lowest body of fresh water on planet earth. There He descended below all things to rise above all things. In Solomon’s temple, the baptismal font was supported by twelve oxen that symbolized the twelve tribes of Israel. … From the baptismal font of the temple, we progress upward through the telestial and terrestrial realms to the room that represents the celestial home of God.

About the difference between coming into the presence of God through heavenly ascent and through temple ritual, Andrew F. Ehat writes (A. F. Ehat, Who Shall Ascend, pp. 53–54):

As Moses’ case demonstrates [see Moses 1], the actual endowment is not a mere representation but is the reality of coming into a heavenly presence and of being instructed in the things of eternity. In temples, we have a staged representation of the step-by-step ascent into the presence of the Eternal while we are yet alive. It is never suggested that we have died when we participate in these blessings. Rather, when we enter the celestial room, we pause to await the promptings and premonitions of the Comforter. And after a period of time, mostly of our own accord, we descend the stairs, and resume the clothing and walk of our earthly existence. But there should have been a change in us as there certainly was with Moses when he was caught up to celestial realms and saw and heard things unlawful to utter.

22 See, e.g., J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 37ff; J. M. Bradshaw et al., Moses 1; J. M. Bradshaw et al., By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified (TMZ 4); J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity.

23 H. W. Nibley, Apocryphal, p. 312; cf. pp. 310–311. See W. W. Isenberg, Philip, 85:14–16, p. 159.

24 R. M. Nelson, Teachings, May 2001, p. 365.

25 On the prophetic commission of Isaiah, see J. M. Bradshaw, How Might We Interpret.

26 For example, see the accounts preserved in P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch; F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch; G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1; G. W. E. Nickelsburg et al., 1 Enoch 2; L. T. Stuckenbruck, Book of Giants; J. C. Reeves, Jewish Lore; J. C. Reeves et al., Enoch from Antiquity 1. For an overview of these various accounts, see Essay #5.

27 See J. M. Bradshaw et al., Moses 1.

28 See Essays #33-41.

29 See Essays #1, 2, 22, 25–29.

30 A. E. Paulsen-Reed, Origins, p. 102.

31 Psalm 110:4; Hebrews 5:6–10; 6:20; 7:1–28; Alma 13:1–19. See also clarifications given in JST Hebrews 7:3, 19–21, 25–26. See also J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 53–58.

32 J. M. Bradshaw, Ezekiel Mural.

33 E.g., C. H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Glory. On the rise of temple terminology and forms in the synagogue and the expanded centrality of prayer during the Amoraic period, see J. Magness, Heaven.

34 R. M. Nelson, Teachings, 22 June 2014, p. 365.

35 For examples of relevant temple rites in the ancient Near East, see, e.g., J. M. Bradshaw et al., Investiture Panel; H. W. Nibley, Message (2005); M. B. Hundley, Gods in Dwellings.

36 For overviews of practices of temple worship worldwide, see, e.g., J. M. Lundquist, Meeting Place; D. Ragavan, Heaven on Earth.

37 J. M. Bradshaw, Now That We Have the Words.

38 J. A. Fitzmyer, First Corinthians, p. 501 in connection with J. M. Bradshaw, Now That We Have the Words, p. 60 n. 8.

39 J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 21 May 1843, 305. For a discussion of the authenticity of this controversial phrase, see J. M. Bradshaw, Now That We Have the Words, pp. 61–66; J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, p. 75 n. 67.

40 English translations can be found in H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), 1–5:23, pp. 515–524; Cyril of Jerusalem, Five.

41 H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), p. 515.

42 For a readable account of Muhammad’s night journey, see D. C. Peterson, Muhammad (2001), pp. 527–529. Similarities between the Jewish Merkabah literature and Islamic mi’raj accounts are described in A. Schimmel, Messenger, p. 298 n. 8.

43 D. C. Peterson, Muhammad (2001), p. 527.

44 Ibid., pp. 528–529.

45 A. Schimmel, Messenger, p. 160.

46 No relationship to the English word “mirage.” See W. J. Hamblin et al., Temple, p. 136; M. Ibn Ishaq ibn Yasar, Sirat Rasul.

47 W. J. Hamblin et al., Temple, p. 136 n. 134.

48 See S. A. Ashraf, Inner, pp. 119–125; J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 177–179, 219, 299 n. 4–7, 645–648; J. M. Bradshaw, What Did Joseph Smith Know, pp. 12–13.

49 S. A. Ashraf, Inner, p. 125.

50 Exodus 33:11.

51 Joseph Smith—History 1:14–20. Don Bradley has argued that the First Vision was Joseph Smith’s initiation as a seer and constituted a kind of endowment (D. Bradley, Acquiring an All-Seeing Eye: Joseph Smith’s First Vision as Seer Initiation and Ritual Apotheosis, 19 July 2010, cited with permission. Cf. D. Bradley, Joseph Smith’s First Vision as Endowment)—though perhaps the term “heavenly ascent” may be more appropriate than “endowment” in this case. Acknowledging that the earliest extant account of the First Vision does not appear to modern readers to be anything like an endowment experience, Bradley writes:

Smith’s vision looks like a typical conversion vision of Jesus (insofar as a Christophany can be typical—that is, it shares a common pattern) when the account from his most “Protestant” phase is used and is set only in the context of revivalism. Yet there is no reason to limit analysis only to that account and that context. All accounts, and not only the earliest, provide evidence for the character of the original experience. Indeed, literary scholars Neal Lambert and Richard Cracroft (N. E. Lambert et al., Literary Form) have argued from their comparison of the respectively constrained and free-flowing styles of the 1832 and 1838 accounts that the former attempts to contain the new wine of Smith’s theophany in an old wineskin of narrative convention. While the 1838 telling, in which the experience is both a conversion and a prophetic calling, is straightforward and natural, the 1832 account seems formal and forced, as if young Smith’s experience was ready to burst the old wineskin or had been shoehorned into a revivalistic conversion narrative five sizes too small.

Noting that “latter-day revelation gives us the fuller account and meaning of what actually took place on the Mount” where Moses came into the presence of the Lord (Moses 1), Elder Alvin R. Dyer saw a similarity between the heavenly ascent of Moses and that of Joseph Smith in the First Vision (A. R. Dyer, Meaning, Meaning, p. 12).

52 Ether 3:6–28. For a detailed analysis of this vision, including its allusions to temple themes, see M. C. Thomas, Brother of Jared.

53 G. E. Smith, Schooling.

54 See D. Bradley, Lost 116 Pages, especially pp. 193–208, 234–240, 252–258, 286–287.

55 Ibid., p. 199.

56 See J. M. Bradshaw, What Did Joseph Smith Know, especially pp. 2–11, 36.

57 For more on Joseph Smith’s early knowledge of temple matters, see ibid.

58 Essay #32.