Book of Moses Essay #44

Moses 1

With contribution by Mark J. Johnson

This Essay continues our look at the literary features of Moses 1. Since Moses 1 leads directly into the narrative flow of JST Genesis, it is natural that it should share stylistic and literary features of the Hebrew Bible (our Old Testament). Below, we will highlight three topics: parallelism, Hebraisms, and figures of speech or idioms.

Parallelism

The most important thing to know about Hebrew thought is that it sought beauty and balance in writings by the use of repetition. While Western poetry is largely based on rhyming of sounds, the prose and poetry of the biblical text finds greater value in what one might call the rhyming of ideas. In other words, poetic verse and narrative structure were built on the foundation of repetition. Jack R. Lundbom emphasizes that, “repetition is the single most important feature of ancient Hebrew rhetoric, being used for emphasis, wordplays, expressing the superlative, creating pathos, and structuring both parts and wholes of prophetic discourse. Its importance can hardly be overestimated. Repetitions can be sequential or placed in strategic collocations to provide balance. … [They] can form a tie-in between the beginning and the end.”1

Forms of repetition can be visible from the minute level of strophes and stanzas in poetry, to multiline units such as poems, speeches, and oracles. The principles of repetition are also seen in the structuring of character arcs and even as the backbone of whole books. This type of repetition is frequently called parallelism.

Because of the differing size and scope of repetition as well as their presence in both poetry and prose, scholars have differing opinions about what can be truly classified as parallelism.2 Donald W. Parry’s perspective positions parallelism equally with poetry and prose, noting that “not all parallelistic forms are poetic, for parallelism serves in a variety of rhetorical and literary functions.”2

Synonymous Parallelism

This type of parallelism “sets forth [its] ideas in the first line, then restates, reinforces or reconfigures them in the next line.”4 Note this example from the early chapters of Genesis.

Adah and Zillah

Hear my voice;

Ye wives of Lamech

hearken unto my speech. (Genesis 4:23)

“Adah and Zillah” are mirrored in the second line with “Ye wives of Lamech” while Lamech’s declaration is repeated with “Hear my voice” and “Hearken unto my speech.”

The same type of parallelism can be found in Moses 1:

For my works

are without end,

and also my words

for they never cease. (Moses 1:4)

The use of synonymous parallelism shows God equating his works with his words. Both, he says, are endless.

Synthetic Parallelism

Parry notes that this type of parallelism “is composed of two lines, neither of which are synonymous or antithetical. Rather, line one presents a declaration and line two gives something new or instructive to the first line.”5 Examples include Proverbs 1:7 and 2 Nephi 2:25. An oft quoted verse in the Book of Moses is also written in this form:

For behold, this is my work and my glory—

to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man. (Moses 1:39)

Inverted Parallelism

Inverted Parallelism, or Chiasmus, is a type of parallelism where the repetition of elements is in an inverted order, rather than sequential. D. Lynn Johnson6 has made note of this arrangement in Moses 1:

A And it came to pass, as the voice was still speaking,

Moses cast his eyes and beheld the earth,

B yea, even all of it; and there was not a particle of it which he did not behold,

C discerning it by the Spirit of God.

D And he beheld also the inhabitants thereof,

D’ and there was not a soul which he beheld not;

C’ and he discerned them by the Spirit of God;

B’ and their numbers were great, even numberless as the sand upon the sea shore.

A’ And he beheld many lands; and each land was called earth, and there were inhabitants on the face thereof. (Moses 1:27-29)

Hebraisms

A Hebraism is a distinctive element of Hebrew occurring in another language. This includes traces of its unique characteristics which are still apparent even after translation. The presence of Hebraisms in the scriptural text are significant since they are grammatically problematic in the English language but are characteristic of good Hebrew grammar. The presence of Hebraic features would be indicative of Moses 1 being an ancient text.

Relative Clauses

John A. Tvedtnes described the relative clause: “In Hebrew, the word that marked the beginning of the clause (generally translated which or who in English) does not always closely follow the word it refers back to, as it usually does in English.”7 This type of construction is also manifest in the Book of Mormon and in Moses 1:

But ye know that the Egyptians were drowned in the Red Sea,

who were the armies of Pharaoh. (1 Nephi 17:27)and by the Son I created them,

which is mine Only Begotten. (Moses 1:33)

Compound Prepositions

Simple prepositions are words such as in, on, under, after, and around, that establish a relationship between a noun and a pronoun. Compound prepositions perform the same function, but with a combination of prepositions which act as a single word. Examples include on top of, in front of, or over against. Parry demonstrates one example from the Old Testament, “The Lord God of Israel hath dispossessed the Amorites from before his people Israel” (Judges 11:23, emphasis added).8 Moses 1:1 contains an example of a compound preposition, where “Moses was caught up into an exceeding high mountain.”

Possessive Pronouns

The English language favors minimal use of possessive pronouns, while “Biblical Hebrew … regularly repeats [these] pronouns” to form them as a type of list.9 Compare this example from the Book of Joshua with Moses 1:

ye will save alive my father, and my mother, and my brethren, and my sisters (Joshua 2:13)

and there is no end to my works, neither to my words. For behold, this is my work and my glory (Moses 1:38-39)

Resumptive Repetition

The biblical authors often needed to offer additional explanation as they told their narratives, so they employed a technique that modern scholars have called resumptive repetition.10 The English language would add an aside to its discourse by the use of parenthesis, commas or dashes, and then continue with the original thought. The Bible, on the other hand, returns to its subject by repeating a key phrase from earlier in the narrative.

Here is an example of resumptive repetition in the Old Testament:

And the children of Israel went into the midst of the sea upon the dry ground: and the waters were a wall unto them on their right hand, and on their left.

And the Egyptians pursued, and went in after them to the midst of the sea, even all Pharaoh’s horses, his chariots, and his horsemen.

…

And Moses stretched forth his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to his strength when the morning appeared; and the Egyptians fled against it; and the Lord overthrew the Egyptians in the midst of the sea.

And the waters returned, and covered the chariots, and the horsemen, and all the host of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them; there remained not so much as one of them.

But the children of Israel walked upon dry land in the midst of the sea; and the waters were a wall unto them on their right hand, and on their left. (Exodus 14:22-23, 27-29)

And here is a similar example from Moses 1:

And, behold, thou art my son; wherefore look, and I will show thee the workmanship of mine hands; but not all, for my works are without end, and also my words, for they never cease.

Wherefore, no man can behold all my works, except he behold all my glory; and no man can behold all my glory, and afterwards remain in the flesh on the earth.

And I have a work for thee, Moses, my son; and thou art in the similitude of mine Only Begotten; and mine Only Begotten is and shall be the Savior, for he is full of grace and truth; but there is no God beside me, and all things are present with me, for I know them all.

And now, behold, this one thing I show unto thee, Moses, my son, for thou art in the world, and now I show it unto thee. (Moses 1:4-7)

Figures of Speech

Understanding particular figures of speech (or idioms) is an important tool as these features illuminate the meanings of text when a more literal reading would be insufficient.

Antenantiosis

This figure of speech is “the practice of stating a proposition in terms of its opposite.”11 Two negatives are combined in a statement, one of which cancels the other out thereby creating a positive. Compare an example from the Proverbs with a verse from Moses 1:

the wicked shall not be unpunished:

but the seed of the righteous shall be delivered (Proverbs 11:21)And he beheld also the inhabitants thereof,

and there was not a soul which he beheld not. (Moses 1:28a)

The technique of antenantiosis combines “not a soul” with “beheld not” to emphasize that Moses saw every living soul in his vision.

Litotes

Litotes is a figure of speech where something is dramatically understated in order to enhance or elevate something else. This is starkly apparent in Moses 1:10 where Moses declares that he is nothing in comparison to the glory and power of the Almighty and Endless God. Compare this statement with Abraham’s discussion with the Lord over the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah:

Now, for this cause I know that man is nothing, which thing I never had supposed. (Moses 1:10)

Then Abraham spoke up again: “Now that I have been so bold as to speak to the Lord, though I am nothing but dust and ashes, what if the number of the righteous is five less than fifty? Will you destroy the whole city because of five people?” (Genesis 18:27-28, NIV)

Not unlike Moses, Abraham acknowledges the might of God by comparing himself to dust and ashes.

Polysyndeton

Polysyndenton is a Greek word that translates to mean “many conjunctions” or more commonly “many ands.”12 This rhetorical device enumerates lists of things, but with the purpose of affecting the pace of the narrative. Bullinger notes that this form is designed to catch the attention of the reader and to isolate individual items in the list for singular consideration.13 Consider its use in 1 Samuel and in Moses 1:

And David said unto Saul, Thy servant kept his father’s sheep,

and there came a lion,

and a bear,

and took a lamb out of the flock:

And I went out after him,

and smote him,

and delivered it out of his mouth:

and when he arose against me, I caught him by his beard,

and smote him,

and slew him. (1 Samuel 17:34-35)And it came to pass that Moses looked,

and beheld the world upon which he was created;

and Moses beheld the world

and the ends thereof,

and all the children of men which are,

and which were created;

of the same he greatly marveled and wondered. (Moses 1:8)

Synecdoche

Where the part of something is used to represent the whole. Moses 1:1 and 1:11 use this figure, where speaking ‘face to face’ represents being in God’s whole presence:

He who has clean hands and a pure heart,

who does not lift up his soul to an idol

or swear by what is false. (Psalm 24:4)And he saw God face to face,

and he talked with him (Moses 1:2)

Conclusion

The importance of understanding these forms and figures of speech is not to just recognize ancient Hebraic literary features in Moses 1, but also to help us read the scriptural texts as their authors intended. Recognizing the forms that ancient authors used to persuade their readers with power brings latter-day readers closer to seeing and hearing as their counterparts did long ago.

In closing, David Noel Freedman elucidates an attitude toward literary form and features that should be remembered by Latter-day Saint students of the scriptures. He speaks specifically of parallelism, but his words can be applied to everything we have discussed in this Essay. He said: “I am confident that the reader will readily agree … that the study of parallelism is, above all else, fun.”14

This Essay is adapted and expanded from Johnson, Mark J. “The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Further Reading

Berlin, Adele. The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism. Revised and Expanded ed. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2008.

Johnson, Mark J. “The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Parry, Donald W. Preserved in Translation: Hebrew and Other Ancient Literary Forms in the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2020.

References

Berlin, Adele. The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism. Revised and Expanded ed. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2008.

Bullinger, E. W. Figures of Speech Used in the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Bake Book House, 1968.

Johnson, Mark J. “The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86.

Lundbom, Jack R. Biblical Rhetoric and Rhetorical Criticism. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2015.

Parry, Donald W. “Hebraisms and other ancient pecularities in the Book of Mormon.” In Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and John W. Welch, 155-189. Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002.

———. Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon. Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2007. https://publications.mi.byu.edu/publications/bookchapters/Poetic_Parallelisms_in_the_Book_of_Mormon_The_Complete_Text_/Poetic%20Parallelisms%20in%20the%20Book%20of%20Mormon.pdf. (accessed August 9, 2017).

———. Preserved in Translation: Hebrew and Other Ancient Literary Forms in the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2020.

Tvedtnes, John A. “The Hebrew background of the Book of Mormon.” In Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, edited by John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne, 77-91. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991. http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/publications/books?bookid=72&chapid=867. (accessed March 22).

Welch, John W. “Antenantiosis in the Book of Mormon.” In Reexploring the Book of Mormon, edited by John W. Welch, 96-97. Salt Lake City, UT and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992. https://archive.bookofmormoncentral.org/node/175. (accessed May 3, 2020).

Notes on Figures

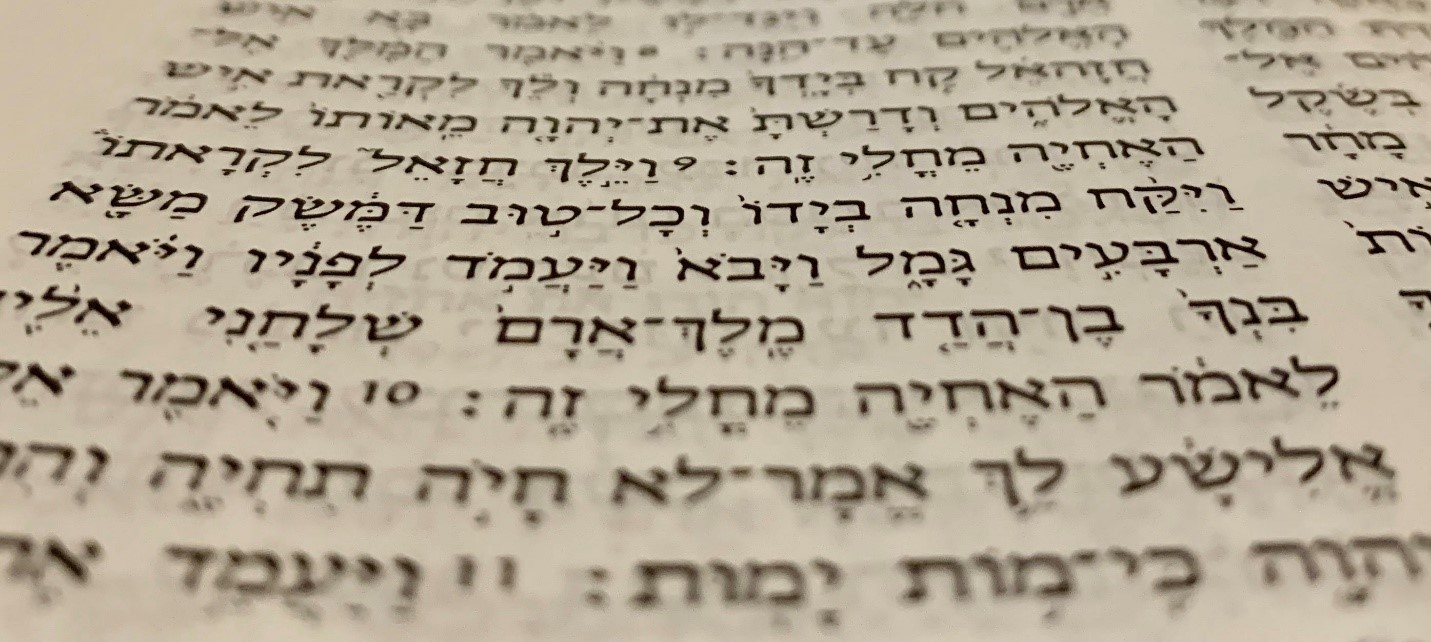

Figure 1. Photograph by Mark J. Johnson.

Footnotes

1 J. R. Lundbom, Biblical Rhetoric, pp. 167–68.

2 For a useful discussion, see A. Berlin, Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism, pp. 1–7.

3 D. W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms, p. xi.

4 D. W. Parry, Preserved in Translation, p. 13.

5 D. W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms, p. xxiv.

6 http://www.ldsgospeldoctrine.net/dlj/TheVisualScriptures-PearlofGreatPrice.pdf.

7 J. A. Tvedtnes, Hebrew Background, p. 87.

8 {Parry, 2002 #6565}, p. 172.

9 D. W. Parry, Preserved in Translation, p. 61.

10 D. W. Parry, Preserved in Translation, p. 57.

11 J. W. Welch, Antenantiosis, p. 96.

12 The use of the technicque of“many ands” as a syntactical technique is explored further in {Johnson, 2020 #6435}.

13 E. W. Bullinger, Figures of Speech, p. 210.

14 David Noel Freedman, Foreword to A. Berlin, Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism, p. xi.