Joseph Smith–History Insight #6

During his lifetime, Joseph Smith provided four firsthand accounts of his First Vision.1 These primary accounts serve as the foundation for understanding the Prophet’s early history and prophetic call. During his lifetime, however, Joseph also on occasion recounted his First Vision to trusted friends and the public at large. Those who heard him retell the First Vision story then recorded these rehearsals in both published works and private journals. These secondary accounts act as important historical data in two important ways: first, they capture some details about the vision that Joseph himself did not preserve in his firsthand accounts, and second, they serve as evidence that even though he was overall reticent to speak too much about it, Joseph was nevertheless telling others about the First Vision during his lifetime.2 A look at the known contemporary secondhand accounts of the First Vision is helpful to fully capture and appreciate what Joseph saw, heard, and felt on that important occasion.

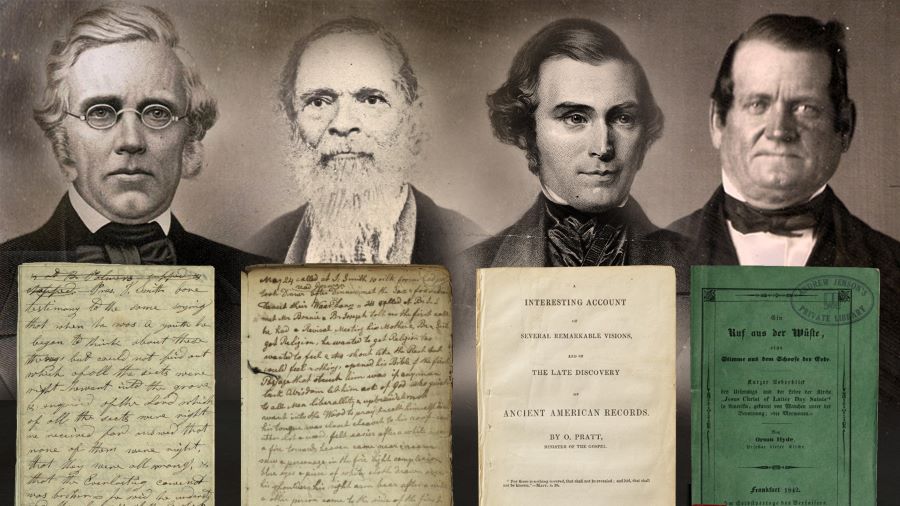

Orson Pratt, A[n] Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions

In 1840, while on a mission in the British Isles, apostle Orson Pratt published A[n] Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, and of the Late Discovery of Ancient American Records as a missionary tract. “Pratt began his thirty-one-page pamphlet by describing [Joseph Smith]’s first vision of Deity and the later visit [Joseph] received from ‘the angel of the Lord.’” In addition, “He summarized the contents of the Book of Mormon, reprinted the statements of two groups of witnesses who saw the gold plates, and concluded with a fifteen-point ‘sketch of the faith and doctrine of this Church.’”3 In this tract, Pratt hit upon most of the major points narrated by Joseph himself in his earlier accounts of the First Vision, including his confusion over which Christian denomination of his day was the true faith, his reliance on James 1:5 to find guidance, retiring to a grove of trees to pray, seeing “two glorious personages, who exactly resembled each other in their features or likeness,” being forgiven of his sins, and being told to join none of the existing churches.4 Pratt’s 1840 telling of the First Vision emphasizes the factor of reason, which told Joseph’s mind that there was only “one doctrine,” one “Church of Christ,” to be known with “certainty,” through “positive and definite evidence.” Pratt was also the first to mention that the bright light that descended on Joseph was so intense that the boy “expected . . . the leaves and boughs of the trees [to be] consumed.”5

Pratt’s pamphlet proved to be highly influential. “The first American edition was printed in New York in 1841, and reprints appeared in Europe, Australia, and the United States.” Although not a firsthand source from Joseph Smith himself “because [he] did not write it, assign it, or supervise its creation,” some of the language and content of A[n] Interesting Account was nevertheless appropriated by the Prophet in his 1842 “Church History” editorial that included a narrative of the First Vision.6 At the same time, it obvious that Pratt knew about the First Vision before leaving for the British Isles from either Joseph directly or from his papers, and it is possible that Pratt had been instructed by Joseph on some of the details to publish about the First Vision once in Europe, thus accounting for these consistencies.

Orson Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste

Two years after Pratt published A[n] Interesting Account another apostle, Orson Hyde, published a missionary tract in Germany titled Ein Ruf aus der Wüste, eine Stimme aus dem Schoose der Erde (A Cry out of the Wilderness, A Voice from the Bowels of the Earth). Using Pratt’s A[n] Interesting Account as his “principle source,”7 Hyde touched on the same points as Pratt in his retelling of the First Vision. One detail included by Hyde but not by Pratt, however, is that as Joseph prayed in the grove “the adversary” filled his “mind with doubts and . . . . all manner of inappropriate images [that] prevent[ed] him from obtaining the object of his endeavors.”8 Although Hyde’s overseas pamphlet did not become as popular or influential as Pratt’s, it is significant as “the first account [of the First Vision] published in a language other than English.”9

Levi Richards, Journal, 11 June 1843

In a meeting at the temple in Nauvoo, Illinois on the evening of June 11, 1843, Levi Richards, one of the Prophet’s clerks and a Church historian, heard Joseph give an account of his First Vision.10 This retelling came right after Elder George Adams spoke on the Book of Mormon and passages from Isaiah 24, 28, and 29 concerning the apostasy from Christ’s everlasting covenant. After summarizing Adams’ remarks, Richards then recorded,

Pres. J. Smith bore testimony to the same— saying that when he was a youth he began to think about these

thesethings but could not find out which of all the sects were right— he went into the grove & enquired of the Lord which of all the sects were right— re received for answer that none of them were right, that they were all wrong, & that the Everlasting covena[n]t was broken.11

That the Prophet would focus this rehearsal of the First Vision on Christ’s affirmation of the reality of the Great Apostasy (a detail present in each of Joseph’s extant firsthand accounts) is understandable given the context of the message Adams had just delivered. As with the 1832 firsthand account which focuses heavily on Joseph’s personal quest for forgiveness of his sins,12 this secondary account recorded by Richards indicates that on occasion Joseph preferred emphasizing certain aspects of his vision to given audiences and to illustrate specific theological points.

David Nye White, Interview with Joseph Smith, 21. August 1843

A few months after this June 1843 meeting, a journalist named David Nye White, senior editor of the Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, interviewed Joseph for his paper while travelling through Nauvoo and the nearby area.13 “During the conversation that ensued, the Prophet related the circumstances of his 1820 vision.”14 In this interview, Joseph reiterated the familiar points present in his earlier accounts, with the added detail that the specific place in the grove where he prayed was in a clearing that had a “stump where [he] had stuck [his] axe when [he] had quit work” the previous day (presumably).

Alexander Neibaur, Journal, 24 May 1844

The final contemporary secondary account of the First Vision comes from Alexander Neibaur, a trusted Jewish German friend of the Prophet’s who had joined the Church in England in 1837some years previously and had immigrated to Nauvoo four years later.15 “In May 1844 Neibaur was present at a small gathering to which Joseph gave an account of his vision just a month before he was murdered.”16 Included in this gathering was a certain person identified as a “Mr Bonnie” by Neibaur, meaning probably Edward Bonney,17 who was not a member of the Church (and indeed was not even very religious per se) but was a member of the Council of Fifty.18

In this mixed audience of close confidants and as preserved in Neibaur’s “sincere, unpolished style that one would expect from a humble devotee not used to writing in English,”19 Joseph retold how “he wanted to get Religion too wanted to feel & shout like the Rest but could feel nothing.” Importantly, Neibaur preserved Joseph’s only description of the personage who otherwise “def[ied] all description” (Joseph Smith–History 1:17) as “light complexion blue eyes a piece of white cloth drawn over his shoulders his right arm bear after a w[h]ile a other person came to the side of the first.” Considering the audience and this intimate context, “there is a strong possibility that . . . though recorded by Neibaur, [this retelling of the First Vision] may have been given primarily for the benefit of the Prophet’s non-religious friend and Council of the Fifty member, Edward Bonney.”20 Neibaur’s account echoes details that span the full range of the primary First Vision accounts from 1832 down to the versions published in the final years of Joseph’s life.

It should be remembered that these are the known contemporary secondhand accounts of the First Vision. It is almost certain that Joseph told more individuals about his vision but that these retellings were not recorded or have not survived.21 Later reminiscences from individuals who knew Joseph corroborate this. For instance, Joseph Curtis remembered Joseph providing an account of his First Vision in 1835 while visiting the Saints in Michigan.22 Edward Stevenson recalled late in his life that in 1834 he along with “many large congregations” heard the Prophet “testif[y] with great power concerning the visit of the Father and the Son, and the conversation he had with them.”23 And Mary Isabella Horne recounted how she first met Joseph as a young woman while living in Toronto, Canada in the fall of 1837 and remembered hearing him “relate his first vision, when the Father and the Son appeared to him; [and] also his receiving the gold plates from the Angel Moroni.”24 Although these reminiscences must be accepted cautiously because of their secondhand nature and in some cases because of their great distance from the time of the events, they are consistent with Joseph’s own firsthand accounts and are reinforced by the known fact that the Prophet was indeed telling others (including non-Latter-day Saints such as Robert Matthews and Erastus Holmes) about his vision during the mid-1830s.25

When brought together, these firsthand and secondary accounts constitute “the entire known historical record that relates directly to the contemporary descriptions of Joseph Smith’s first vision” and potentially make that vision “the best documented theophany in history.”26

Footnotes

1 Dean C. Jessee, “The Early Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” BYU Studies 9, no. 3 (1969): 275–294; James B. Allen and John W. Welch, “Analysis of Joseph Smith’s Accounts of His First Vision,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820–1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2017), 37–77.

2 For an overview of these accounts, see Milton V. Backman, Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971; 2nd edition, 1980), 170–177; Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision: A Guide to the Historical Accounts (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 54–66.

3 Karen Lynn Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844 (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 519.

4 Pratt, A[n] Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, 3–5, reproduced in Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 522–524.

5 Pratt, A[n] Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, 5, reproduced in Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 524.

6 Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 519–520.

7 Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 519.

8 Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste, 14–15, English translation via the Joseph Smith Papers website. The German original reads: “Er umnachtete seinen Verstand mit Zweifeln und führte seiner Seele allerlei unpassende Bilder vor, um ihn an der Erreichung des Gegenstandes seiner Bestrebungen zu hinder.”

9 Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision: A Guide to the Historical Accounts (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 60.

10 Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 63–64.

11 Levi Richards, Journal, 11 June 1843, extract, pp. [15–16]

12 See Pearl of Great Price Central, “The 1832 First Vision Account,” Joseph Smith–History Insight #2 (February 6, 2020).

13 David White, “The Prairies, Nauvoo, Joe Smith, the Temple, the Mormons, &c.,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (September 15, 1843); reprinted in Dean C. Jessee, The Papers of Joseph Smith, Volume 1: Autobiographical and Historical Writings (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989), 438–444.

14 Jessee, The Papers of Joseph Smith, Volume 1, 443.

15 Jessee, The Papers of Joseph Smith, Volume 1, 459–461.

16 Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 65.

17 Jessee, The Papers of Joseph Smith, Volume 1, 459.

18 See “Bonney, Edward William” online at the Joseph Smith Papers website; Quinten Zehn Barney, “A Contextual Background for Joseph Smith’s Last Known Recounting of the First Vision,” 8–9, unpublished manuscript in authors’ possession, cited with permission.

19 Allen and Welch, “Analysis of Joseph Smith’s Accounts of His First Vision,” 55.

20 Barney, “A Contextual Background for Joseph Smith’s Last Known Recounting of the First Vision,” 8.

21 See Steven C. Harper, First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 53–57.

22 Joseph Curtis reminiscences and diary, 1839 October-1881 March, p. 5 (CHL MS 1654). Historian Steven C. Harper, First Vision, 53, dates this retelling to 1839.

23 Edward Stevenson, Reminiscences of Joseph, the Prophet, And the Coming Forth of The Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Edward Stevenson, 1893), 4. Stevenson, born in 1820, would have been a teenager when he first heard Joseph Smith recount his First Vision. Although the year is different, it is possible that Stevenson is recounting the same occasion of Joseph preaching in Michigan as in Curtis’ reminiscence. At the very least, these two sources corroborate the idea that Joseph was telling others his First Vision story in the mid-1830s.

24 “Testimony of Sister M. Isabella Horne,” Woman’s Exponent, June 1910, 6. Horne died in 1905, which means although her reminiscence was published in 1910, it was recounted some years earlier. In the fall of 1837 when she first met Joseph Smith she would have been about 19 years old.

25 On the contemporary retellings of the First Vision to Matthews and Holmes, see Journal, 1835–1836, 23–24, 36–37. See further Matthew B. Brown, A Pillar of Light: The History and Message of the First Vision (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2009), 195–215; Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 54n13.

26 Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 66, 31.