Book of Moses Essay #28

Moses 7:28-43

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Jacob Rennaker, and David J. Larsen

The tradition of a weeping prophet is perhaps best exemplified by Jeremiah who cried out in sorrow:

Oh that my head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the slain of the daughter of my people!1

In another place, he wrote:

Let mine eyes run down with tears night and day, and let them not cease: for the virgin daughter of my people is broken with a great breach, with a very grievous blow.2

Less well-known is the ancient Jewish tradition of Enoch as a weeping prophet. In the pseudepigraphal book of 1 Enoch, his words are very near to those of Jeremiah:

O that my eyes were a [fountain]3 of water, that I might weep over you; I would pour out my tears as a cloud of water, and I would rest from the grief of my heart.4

We find the pseudepigraphal Enoch, like Enoch in the Book of Moses, weeping in response to visions of mankind’s wickedness. Following the second of these visions in 1 Enoch, he is recorded as saying:

And after that I wept bitterly, and my tears did not cease until I could no longer endure it, but they were running down because of what I had seen. … I wept because of it, and I was disturbed because I had seen the vision.5

In the Apocalypse of Paul, the apostle meets Enoch, “the scribe of righteousness”6 “within the gate of Paradise,” and, after having been cheerfully embraced and kissed,7 sees the prophet weep, and says to him, “‘Brother, why do you weep?’ And again sighing and lamenting he said, ‘We are hurt by men, and they grieve us greatly; for many are the good things which the Lord has prepared, and great is his promise, but many do not perceive them.’”8 A similar motif of Enoch weeping over the generations of mankind can be found in the pseudepigraphal book of 2 Enoch.9 “There is, to say the least,” writes Hugh Nibley “no gloating in heaven over the fate of the wicked world. [And it] is Enoch who leads the weeping.”10

It is surprising that so little has been done to compare modern revelation with ancient sources bearing on the weeping of Enoch.11 Mere coincidence is an insufficient explanation for Joseph Smith’s association of weeping with Enoch, as it is a motif that occurs nowhere in scripture or other sources where the Prophet might have seen it,12 and similar accounts of weeping are not associated with comparable figures in his translations and revelations.13

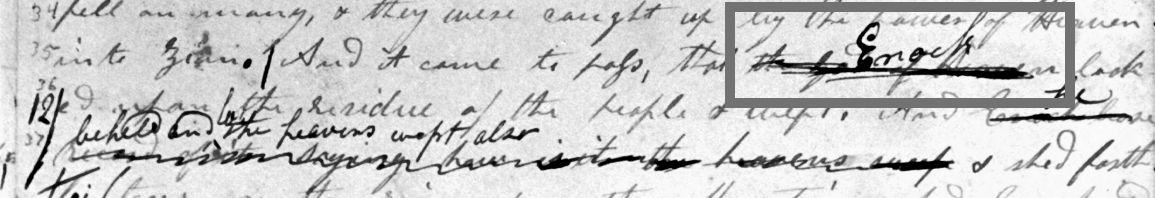

Besides Moses 7:41 and 49, we find two additional descriptions of Enoch’s weeping. The first instance is to be found in the words of a divinely-given song, recorded in Joseph Smith’s Revelation Book 2, where Enoch is said to have “gazed upon nature and the corruption of man, and mourned their sad fate, and wept.”14 The second instance is in Old Testament Manuscript 2 of the Joseph Smith Translation, where the revelatory account was corrected to say that it was Enoch rather than God who wept.

Did God or Enoch Weep in Moses 7:28?

The Prophet’s first dictation of Moses 7:28 follows the description of Old Testament Manuscript 1 (OT1), where it is God who weeps:

the g God of heaven looked upon the residue of the peop[le a]nd he wept15

and a subsequent revision, correcting the text so it reads that Enoch wept:

the God of Heaven look=ed upon the residue of the people & wept16

The first dictation above is the one that has been retained in the current canonical version of the Book of Moses. In line with narrative considerations discussed in a previous Essay,17 we think that it makes more sense in the context of the overall passage to understand Enoch as having deferred his weeping until Moses 7:41, after God completes his speech. Thus, for this and other reasons outlined elsewhere,18 we take the OT1 version of Moses 7:28, where the text states that God wept, to be the best reading of the verse, unless and until better arguments for the OT2 reading come along.19

Within the theme of the weeping Enoch, there are several

specific sub-themes that are common in both the Book of Moses and in ancient

literature:

· Weeping in similitude of God

· Weeping because the Divine withdraws from the earth

· Weeping because of the insulting words of the wicked

· Weeping followed by heavenly vision

We will discuss each of these in turn.

Weeping in Similitude of God

In the Midrash Rabbah on Lamentations, Enoch is portrayed as weeping in likeness of God when the Israelite temple was destroyed:

At that time the Holy One, blessed be He, wept and said, “Woe is Me! What have I done? I caused my Shekhinah to dwell below on earth for the sake of Israel; but now that they have sinned, I have returned to My former habitation…” At that time Metatron [who is Enoch in his glorified state] came, fell upon his face, and spake before the Holy One, blessed be He: “Sovereign of the Universe, let me weep, but do Thou not weep.” He replied to him: “if thou lettest Me not weep now, I will repair to a place which thou hast not permission to enter, and will weep there,” as it is said, “But if ye will not hear it, My soul shall weep in secret for pride.”20 21

The dialogue between God and Enoch in this passage is reminiscent of the one in Moses 7:28–41:

28 And it came to pass that the God of heaven looked upon the residue of the people, and he wept; and Enoch bore record of it, saying: How is it that the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains?

29 And Enoch said unto the Lord: How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity? …

Enoch, seeing God weep, was astonished at witnessing the emotional display of the holy, eternal God. In the Book of Moses account, God, in response, proceeds to show Enoch the wickedness of the people of the Earth and how much they will suffer in consequence. After seeing a vision of the misery that would come upon God’s children, Enoch will commiserate with God, weeping inconsolably.22

Speaking of prophets in general, Abraham Heschel explains that “what convulsed the prophet’s whole being was God. His condition was a state of suffering in sympathy with the divine pathos.”23 This view of prophets stands in stark contrast to the Philo of Alexandria’s parallel description of the relationship between the high priest and God in De Specialibus Legibus. In this passage, Philo is commenting upon the law in Leviticus 21:10–12 which prohibits the high priest from mourning for (or even approaching) the bodies of deceased parents, consistent with Greek philosophical conceptions.24

Philo’s view of a dispassionate, yet mediating high priest is not only at odds with the portrayal of Jesus as high priest presented in Hebrews 4:15 (“For we have not an high priest which cannot be touched with the feeling of our infirmities”),25 but also with Heschel’s perspective of mediating prophets as those who have entered into “a fellowship with the feelings of God.”26 As in the case of Enoch, a model of divine sympathy calls into question teachings regarding divine apathy.

This theme of shared sorrow between God and prophet is explored at length by theologian Terence Fretheim.27 According to Fretheim, “The prophet’s life was reflective of the divine life. This became increasingly apparent to Israel. God is seen to be present not only in what the prophet has to say, but in the word as embodied in the prophet’s life. To hear and see the prophet was to hear and see God, a God who was suffering on behalf of the people.”28 To a certain extent, so close was the association between God and prophet that the prophet’s very presence could serve as a sort of “ongoing theophany,”29 providing Israel with a very visible and tangible representation of God’s concern.30

Fretheim argues that the prophet’s “sympathy with the divine pathos” was not the result of contemplating the divine, but rather a result of the prophet’s participation in the divine council. He writes:

[T]he fact that the prophets are said to be a part of this council indicates something of the intimate relationship they had with God. The prophet was somehow drawn up into the very presence of God; even more, the prophet was in some sense admitted into the history of God. The prophet becomes a party to the divine story; the heart and mind of God pass over into that of the prophet to such an extent that the prophet becomes a veritable embodiment of God.31

In the case of Enoch, the prophet enters into the presence of God32 and witnesses the weeping of God and a heavenly host over the wickedness of humanity.33 As a result of this participation in the heavenly council, Enoch becomes divinely sensitized to the plight of the human race and begins to weep himself.34

Weeping Because the Divine Withdrawal from the Earth.

A full chorus of weeping that begins with the Messiah and expands to include the heavens and its angelic hosts is eloquently described in a Jewish mystical text called the Zohar:

Then the Messiah lifts up his voice and weeps, and the whole Garden of Eden quakes, and all the righteous and saints who are there break out in crying and lamentation with him. When the crying and weeping resound for the second time, the whole firmament above the Garden begins to shake, and the cry echoes from five hundred myriads of supernal hosts until it reaches the highest Throne.35

The reason for this weeping “of all the workmanship of [God’s] hands”36 is the loss of the temple—the withdrawal of the divine presence from the earth. In Jewish tradition, this withdrawal is portrayed as having occurred in a series of poignant stages. This is vividly illustrated in Ezekiel 9-11. Because of the priests’ wickedness within the temple precincts, the “glory of the God of Israel” moves from its resting place within the temple compound to the threshold of the temple,37 where it remains for a time. Finally, after surveying the extent of the wicked priests’ actions within the temple, Ezekiel sees the “glory of Yahweh” leave the temple, continue east through the city of Jerusalem, and finally come to rest upon the Mount of Olives.38

This departure of the God of Israel from the great city of Jerusalem was especially significant from the perspectives of the nations who surrounded Israel. According to the Hebrew Bible scholar Margaret Odell, “In ancient Near Eastern thought, a city could not be destroyed unless its god had abandoned it.”39 With the presence of God removed from the city, it now lay exposed and vulnerable to attack, a condition that was exploited by the Babylonians.

The withdrawal of the divine presence from the temple is a fitting analogue to the taking up of Enoch’s Zion from the earth. Whereas in the above passages, where God withdraws his presence, or his glory, due to the wickedness of the people, the Book of Moses40 has God removing the righteous city of Zion in its entirety from among the wicked nations that surround it.

The differences in the two pericopes may actually have more in common than is immediately apparent. In Jewish literature there is a significant correspondence between Zion and the Shekhinah (Divine Presence). Zion is often personified as the Bride of God.41 The word “Shekhinah” is a feminine noun in Hebrew, is often associated with the female personified Wisdom, and is likewise described in later Jewish writings as the Bride of God. The idea of Zion being taken up and the Shekhinah being withdrawn are parallel motifs.

Weeping Because of the Insulting Words of the Wicked

Pheme Perkins correctly argues that:

speech is much more carefully controlled and monitored in a traditional, hierarchical society than it is in modern democracies. We can hardly recapture the sense of horror at blasphemy that ancient society felt because for us words do not have the same power that they do in traditional societies. Words appear to have considerably less consequences than actions. In traditional societies, the word is a form of action.42

Consistent with this idea, a Manichaean text describes an Enoch who weeps because of the harsh words of the wicked:

I am Enoch the righteous. My sorrow was great, and a torrent of tears [streamed] from my eyes because I heard the insult which the wicked ones uttered.43

Elsewhere, Enoch is said to have prophesied a future judgment upon such “ungodly sinners” who have “uttered hard speeches… against [the Lord].”44

Rabbi Eliezer gives examples of such insults:

We don’t need Your drops of rain, neither do we need to walk in Your ways.45

Having been told by Noah that all mankind would be destroyed by the Flood if they did not repent, these same “sons of God” are said to have defiantly replied:

If this is the case, we will stop human reproduction and multiplying, and thus put an end to the lineage of the sons of men ourselves.46

Similarly, in Moses 8:21, we find these examples of truculent boasting in the mouths of the antediluvians:

Behold, we are the sons of God; have we not taken unto ourselves the daughters of men? And are we not eating and drinking, and marrying and giving in marriage? And our wives bear unto us children, and the same are mighty men, which are like unto men of old, men of great renown.

An ancient exegetical tradition cited by John Reeves associates the speech of Job in 21:7–15 “to events transpiring during the final years of the antediluvian era”47 rather than to the time of Job. Likewise, in 3 Enoch these verses are directly linked, not to Job, but to Enoch himself.48 In defiance of the Lord’s entreaty to “love one another, and… choose me, their Father,”49 the wicked are depicted as “say[ing] unto God”:

14 … Depart from us: for we desire not the knowledge of thy ways.

15 What is the Almighty, that we should serve him? And what profit should we have if we pray unto him?50

Reeves characterizes these words as “a blasphemous rejection of divine governance and guidance… wherein the wicked members of the Flood generation verbally reject God.”51

Weeping Followed by Heavenly Vision

In the Cologne Mani Codex, Enoch’s tearful sorrow was directly followed by an angelophany:

While the tears were still in my eyes and the prayer was yet on my lips, I beheld approaching me s[even] angels descending from heaven. [Upon seeing] them I was so moved by fear that my knees began knocking.52

A description of a similar set of events is found in 2 Enoch:

… in the first month, on the assigned day of the first month, I was in my house alone, weeping and grieving with my eyes. When I had lain down on my bed, I fell asleep. And two huge men appeared to me, the like of which I had never seen on earth.53

The same sequence of events, Enoch’s weeping and grieving followed by a heavenly vision, can be found in modern revelation within the song of Revelation Book 2 mentioned earlier:

Enoch… gazed upon nature and the corruption of man, and mourned their sad fate, and wept, and cried out with a loud voice, and heaved forth his sighs: “Omnipotence! Omnipotence! O may I see Thee!” And with His finger He touched his eyes54 and he saw heaven. He gazed on eternity and sang an angelic song.55

Noting that this pattern is not confined to Enoch, Reeves56 writes: “Prayer coordinated with weeping that leads to an angelophany is also a sequence prominent in [other] apocalyptic traditions.”57

Conclusions

Ancient and modern Saints know that all mortal sorrow will be done away at the end time when God shall “gather together in one all things in Christ, both which are in heaven, and which are on earth.”58 God said to Noah that in that day: “thy posterity shall embrace the truth, and look upward, then shall Zion look downward, and all the heavens shall shake with gladness, and the earth shall tremble with joy.”59 Describing the human dimension of the great at-one-ment of the heavenly and earthly Zion, when tears of joy shall replace tears of mourning, is the account of Enoch himself where we read, “Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other.”60

This article is adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Jacob Rennaker, and David J. Larsen. “Revisiting the forgotten voices of weeping in Moses 7: A comparison with ancient texts.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 2 (2012): 41–71.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Jacob Rennaker, and David J. Larsen. “Revisiting the forgotten voices of weeping in Moses 7: A comparison with ancient texts.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 2 (2012): 41–71.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 110–115, 141–152.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 133, 134–136.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, pp. 68–79.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, p. 284.

References

Alexander, Philip S. “3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Black, Jeremy A. “The new year ceremonies in ancient Babylon: ‘Taking Bel by the hand’ and a cultic picnic.” Religion 11, no. 1 (1981): 39-59. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WWN-4MMD1NR-5&_user=9634938&_coverDate=01%2F31%2F1981&_rdoc=5&_fmt=high&_orig=browse&_origin=browse&_zone=rslt_list_item&_srch=doc-info(%23toc%237135%231981%23999889998%23639866%23FLP%23display%23Volume)&_cdi=7135&_sort=d&_docanchor=&_ct=10&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&searchtype=a. (accessed September 16, 2010).

Bowen, Matthew L. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, February 26, 2020.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Jacob Rennaker, and David J. Larsen. “Revisiting the forgotten voices of weeping in Moses 7: A comparison with ancient texts.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 2 (2012): 41-71. www.templethemes.net.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ryan Dahle. “Textual criticism and the Book of Moses: A response to Colby Townsend’s “Returning to the sources”.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (2020): in press. www.templethemes.net.

Cameron, Ron, and Arthur J. Dewey, eds. The Cologne Mani Codex (P. Colon. inv. nr. 4780) ‘Concerning the Origin of His Body’. Texts and Translations 15, Early Christian Literature 3, ed. Birger A. Pearson. Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press, 1979.

Collins, John J. “Sibylline Oracles.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 2, 317-472. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Dahl, Larry E. “The vision of the glories.” In The Doctrine and Covenants, edited by Robert L. Millet and Kent P. Jackson. Studies in Scripture 1, 279-308. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Elliott, J. K. “The Apocalypse of Paul (Visio Pauli).” In The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation, edited by J. K. Elliott, 616-44. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Faulring, Scott H., and Kent P. Jackson, eds. Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible Electronic Library (JSTEL) CD-ROM. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University. Religious Studies Center, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2011.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Fretheim, Terence. The Suffering of God: An Old Testament Perspective. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1984.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. 1962. The Prophets. Two Volumes in One ed. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007.

Klijn, A. F. J. “2 (Syriac Apocalypse of) Baruch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 615-52. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Lichtheim, Miriam, ed. 1973-1980. Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings. 3 vols. Berkeley, CA: The University of California Press, 2006.

MacRae, George W., William R. Murdock, and Douglas M. Parrott. “The Apocalypse of Paul (V, 2).” In The Nag Hammadi Library, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 256-59. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Neusner, Jacob, ed. The Mishnah: A New Translation. London, England: Yale University Press, 1988.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Odell, Margaret. Ezekiel. Smyth and Helwys Bible Commenary. Macon, GA: Smyth and Helwys, 2005.

Ouaknin, Marc-Alain, and Éric Smilévitch, eds. 1983. Chapitres de Rabbi Éliézer (Pirqé de Rabbi Éliézer): Midrach sur Genèse, Exode, Nombres, Esther. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1992.

Perkins, Pheme. First and Second Peter, James, and Jude. Louisville, KY: John Knox, 1995.

Peterson, Daniel C. “On the motif of the weeping God in Moses 7.” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 285-317. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Philo. b. 20 BCE. “The special laws, 1 (De specialibus legibus, 1).” In The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, edited by C. D. Yonge. New Updated ed. Translated by C. D. Yonge, 534-67. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2006.

Reeves, John C. Heralds of that Good Realm: Syro-Mesopotamian Gnosis and Jewish Traditions. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies 41, ed. James M. Robinson and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1996.

Sanders, E. P. “Testament of Abraham.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 1, 871-902. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Sharp, Daniel, and Matthew L. Bowen. “Scripture note — ‘For this cause did King Benjamin keep them’: King Benjamin or King Mosiah?” Religious Educator 18, no. 1 (2017): 81-87. https://rsc.byu.edu/sites/default/files/pub_content/pdf/Scripture_Note%E2%80%94For_This_Cause_Did_King_Benjam%E2%80%8Bin_Keep_Them_King_Benjamin_or_King_Mosiah.pdf. (accessed February 26, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper. Manuscript Revelation Books, Facsimile Edition. The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin and Richard Lyman Bushman. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2009.

———. Manuscript Revelation Books. The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations 1, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin and Richard Lyman Bushman. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2011.

Sparks, Kenton L. Ancient Texts for the Study of the Hebrew Bible: A Guide to the Background Literature. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Sperling, Harry, Maurice Simon, and Paul P. Levertoff, eds. The Zohar: An English Translation. 5 vols. London, England: The Soncino Press, 1984.

Tang, Alex. 2006. A meditation on Rembrandt’s Jeremiah. In Random Musings from a Doctor’s Chair. http://draltang01.blogspot.com/2006/12/meditation-on-rembrandts-jeremiah.html. (accessed April 30, 2013).

Walker, Charles Lowell. Diary of Charles Lowell Walker. 2 vols, ed. A. Karl Larson and Katharine Miles Larson. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1980.

Williams, Frederick Granger. “Singing the word of God: Five hymns by President Frederick G. Williams.” BYU Studies 48, no. 1 (2009): 57-88.

———. The Life of Dr. Frederick G. Williams, Counselor to the Prophet Joseph Smith. Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2012.

Witherington, Ben, III. Letters and Homilies for Jewish Christians: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Hebrews, James and Jude. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2007.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremiah_Lamenting_the_Destruction_of_Jerusalem (accessed April 15, 2020). Public domain. Alex Tang describes the painting as follows (A. Tang, A meditation on Rembrandt’s Jeremiah):

This oil on panel painting is one of the finest works of Rembrandt’s Leiden period. For many years it was incorrectly identified but it certainly shows Jeremiah, who had prophesied the destruction of Jerusalem by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon (Jeremiah 32:28–35), lamenting over the destruction of the city. In the distance on the left a man at the top of the steps holds clenched fists to his eyes—this was the last king of Judah, Zedekiah, who was blinded by Nebuchadnezzar. The prominent burning domed building in the background is probably Solomon’s Temple.

Jeremiah’s pose, his head supported by his hand, is a traditional attitude of melancholy: his elbow rests on a large book which is inscribed ‘Bibel’ on the edge of the pages, probably a much later addition to the painting. The book is presumably meant to be his own book of Jeremiah or the book of Lamentations. Rembrandt is a master of light in art. The lighting of the figure is particularly effective with the foreground and the [left] side of the prophet’s face in shadow and his robe outlined against the rock. Jeremiah’s [gaze] rested on a few pieces of gold and silver vessels which he must have managed to salvage from the burning temple.

In Lamentations, we read of how Jeremiah’s sorrows were assuaged by hope: “For the Lord will not cast off for ever: But though he cause grief, yet will he have compassion according to the multitude of his mercies” (Lamentations 3:31–32. See also Jeremiah 32:36–44; 33:4–26).

Figure 2. S. H. Faulring et al., JST Electronic Library, OT 1–16—Moses 7:10b-28a, Genesis 7:12b-35a. Copyright Community of Christ, 2011. All rights reserved. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Old Testament 1, p. 16, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/old-testament-revision-1/18 (accessed February 19, 2020).

Figure 3. Ibid., OT 2–21 — Moses 7:15b-29b, Genesis 7:19b-35b. Copyright Community of Christ, 2011. All rights reserved. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Old Testament 2, p. 21, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/old-testament-revision-2/26 (accessed February 19, 2020).

Footnotes

1 Jeremiah 9:1. Cf. Isaiah 22:4: “Therefore said I, Look away from me; I will weep bitterly, labour not to comfort me, because of the spoiling of the daughter of my people.”

2 Jeremiah 14:17.

3 The text reads dammana [cloud], which Nickelsburg takes to be a corruption in the Aramaic (ibid., pp. 463-464). Nibley takes the motif of the “weeping” of clouds in this verse to plausibly be a parallel to Moses 7:28 (H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 199). On the other hand, Nibley’s translation of 1 Enoch 100:11–13 as describing a weeping of the heavens is surely a misreading (ibid., p. 198; cf. (G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 100:11-13, pp. 503).

4 G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 95:1, p. 460.

5 G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 90:41-42, p. 402.

6 Another instance of Enoch as a compassionate, “righteous scribe” appears in the Testament of Abraham. The archangel Michael opens to Abraham a vivid view of the heavenly judgment scene, whereupon Abraham asks (E. P. Sanders, Testament of Abraham, 11:1-10 [Recension B], p. 900):

“Lord, who is this judge? And who is the other one who brings the charges of sins?” And Michael said to Abraham, “Do you see the judge? This is Abel, who first bore witness, and God brought him here to judge. And the one who produces (the evidence) is the teacher of heaven and earth and the scribe of righteousness, Enoch. For the Lord sent them here in order that they might record the sins and the righteous deeds of each person.” And Abraham said, “And how can Enoch bear the weight of the souls, since he has not seen death? Or how can he give the sentence of all the souls?” And Michael said, “If he were to give sentence concerning them, it would not be accepted. But it is not Enoch’s business to give sentence; rather, the Lord is the one who gives sentence, and it is this one’s (Enoch’s) task only to write. For Enoch prayed to the Lord saying, ‘Lord, I do not want to give the sentence of the souls, lest I become oppressive to someone.’ And the Lord said to Enoch, ‘I shall command you to write the sins of a soul that makes atonement, and it will enter into life. And if the soul has not made atonement and repented, you will find its sins (already) written, and it will be cast into punishment.’”

Here, Abraham voices the concern that a relatively mortal Enoch (one who “has not seen death”) would not have the capacity to “bear the weight of the souls” who were being judged. However, Enoch exhibits his capacity for compassion and sympathy by taking into account the feelings of those being judged, fearing that he might “become oppressive to someone” should he judge amiss.

7 Following this encounter and embrace, Paul is told by an angel (J. K. Elliott, Apocalypse of Paul, 20, p. 628): “‘Whatever I now show you here, and whatever you shall hear, tell no one on earth.’ And he led me and showed me; and there I heard words which it is not lawful for a man to speak [2 Corinthians 12:4].” In the version of the Apocalypse of Paul found at Nag Hammadi, Paul’s encounter at the entrance to the seventh heaven is told differently (G. W. MacRae et al., Paul, 22:23-23:30, p. 259). At that entrance, Paul is challenged with a series of questions from Enoch. In answer to Enoch’s final question, Paul is instructed: “‘Give him [the] sign that you have, and [he will] open for you.’ And then I gave [him] the sign.” Whereupon “the [seventh] heaven opened.”

8 J. K. Elliott, Apocalypse of Paul, 20, p. 628.

9 F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch, 41:1 [J], p. 166: “[And] I saw all those from the age of my ancestors, with Adam and Eve. And I sighed and burst into tears.”

10 H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 5.

11 Ibid., pp. 5-7, 14, 68, 189, 192, 205 addresses this topic, citing a handful of ancient parallels. D. C. Peterson, Weeping God, p. 296 cites part of the passage from Midrash Rabbah included later in this article, but his focus is on the weeping of God rather than that of Enoch. The present article draws on a 2012 publication: J. M. Bradshaw et al., Revisiting.

12 Richard Laurence first translated the book of Enoch into English in 1821, but it is very unlikely that Joseph Smith would have encountered this work. Revised editions were published in 1833, 1838, and 1842, but these appeared subsequent to the book of Moses account, which was received in 1830.

13 An exception is, of course, Jesus Christ, who is recorded as having wept both in the New Testament (John 11:35) and in the Book of Mormon (3 Nephi 17:21–22; cf. Jacob 5:41). In 2 Nephi 4:26, Nephi once asks “why should my heart weep and my soul linger in the valley of sorrow… ?”

14 J. Smith, Jr. et al., Manuscript Revelation Books, Facsimile Edition, Revelation Book 2, 48 [verso], 27 February 1833, pp. 508-509, spelling and punctuation modernized. The preface to the entry in the revelation book says that it was “sung by the gift of tongues and translated.” An expanded and versified version of this song that omits the weeping of Enoch was published in Evening and Morning Star, (Independence, MO and Kirtland, OH, 1832–1834; repr., Basel Switzerland: Eugene Wagner, 2 vols., 1969), 1:12, May 1833. It has been argued by a descendant of Frederick G. Williams that both the original and versified version of this song should be attributed to his ancestor and namesake. See F. G. Williams, Life, pp. 221-251; F. G. Williams, Singing, pp. 57–88. The editors of the relevant volume of the Joseph Smith Papers note: “An undated broadside of the hymn states that it was ‘sung in tongues’ by David W. Patten and ‘interpreted’ by Sidney Rigdon. (“Mysteries of God.” Church History Library.) This item was never canonized” J. Smith, Jr. et al., Manuscript Revelation Books, p. 377 n. 65.

15 S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, OT 1–16—Moses 7:10b-28a, OT 1–17—Moses 7:28b-7:43, p. 106.

16 Ibid., OT2–21—Moses 7:15b-29a, OT2–22—Moses 7:29b-41a, p. 618.

17 Essay #25.

18 J. M. Bradshaw et al., Textual Criticism.

19 Though we admit it may seem more logical to operate on the assumption that the latest revisions of Joseph Smith’s translations and revelations are always the “best” versions, we have found in our experience that the earliest readings sometimes seem to be superior. After extensive discussion of a relevant example in the Book of Mormon, Matthew Bowen concludes: “We see abundant evidence in ancient New Testament manuscripts of scribes, clerks, and editors attempting to correct what they think are mistakes in the text, only to make the text worse with their corrections.[Joseph Smith and his associates sometimes] did similar things with the Book of Mormon text and with his early revelations” (M. L. Bowen, February 26 2020). For a good example of this in the Book of Mormon, see D. Sharp et al., Scripture Note — “For This Cause” For a discussion of the relative merits of the OT1 and OT2 manuscripts of the Book of Moses, see J. M. Bradshaw et al., Textual Criticism.

20 H. Freedman et al., Midrash, Lamentations 24, p. 41.

21 Jeremiah 13:17.

22 Cf. Noah’s expression of grief in J. J. Collins, Sibylline Oracles, 1:190-191, p. 339: “how much will I lament, how much will I weep in my wooden house, how many tears will I mingle with the waves?”

23 A. J. Heschel, Prophets, 1:118, cf. 1:80–85, 91–92, 105–127; 2:101–103.

24 Philo writes as follows (Philo, Specialibus 1, 1:113-116, pp. 165, 167, emphasis added):

[T]he high priest is precluded from all outward mourning and surely with good reason. For the services of the other priests can be performed by deputy, so that if some are in mourning none of the customary rites need suffer. But no one else is allowed to perform the functions of a high priest and therefore he must always continue undefiled, never coming in contact with a corpse, so that he may be ready to offer his prayers and sacrifices at the proper time without hinderance on behalf of the nation.

Further, since he is dedicated to God and has been made captain of the sacred regiment, he ought to be estranged from all the ties of birth and not be so overcome by affection to parents or children or brothers as to neglect or postpone any one of the religious duties which it were well to perform without any delay. He forbids him also either to rend his garments for his dead, even the nearest and dearest, or to take from his head the insignia of the priesthood, or on any account to leave the sacred precincts under the pretext of mourning. Thus, showing reverence both to the place and to the personal ornaments with which he is decked, he will have his feeling of pity under control and continue throughout free from sorrow.

For the law desires him to be endued with a nature higher than the merely human and to approximate to the Divine, on the border-line, we may truly say, between the two, that men may have a mediator through whom they may propitiate God and God a servitor to employ in extending the abundance of His boons to men.

25 J. Neusner, Mishnah, 1:4-1:6, p. 266 describes weeping as part of the rituals of the high priest on Yom Kippur:

1:4 A. All seven days they did not hold back food or drink from him.

B. [But] on the eve of the Day of Atonement at dusk they did not let him eat much,

C. for food brings on sleep.

1:5 A. The elders of the court handed him over to the elders of the priesthood,

B. who brought him up to the upper chamber of Abtinas.

C. And they imposed an oath on him and took their leave and went along.

D. [This is what] they said to him, “My lord, high priest: We are agents of the court, and you are our agent and agent of the court.

E. “We abjure you by Him who caused his name to rest upon this house, that you will not vary in any way from all which we have instructed you.”

F. He turns aside and weeps.

G. And they turn aside and weep.

1:6 A. If he was a sage, he expounds [the relevant Scriptures].

B. And if not, disciples of sages expound for him.

K. L. Sparks, Ancient Texts, p. 167. has noted that certain aspects of the Israelite Day of Atonement rite “seem to mimic” events of the Mesopotamian akītu festival. The Babylonian king, as part of the ceremonies of the akītu festival, was required to submit to a royal ordeal involving an initial period of suffering and ritual death. Once this phase was complete, the king washed his hands and entered the temple for the rites of (re)investiture, as described in Black’s reconstruction of events. Note the importance of the weeping of the king at this juncture (J. A. Black, New Year, pp. 44-45):

The šešgallu, who is in the sanctuary, comes out and divests the king of his staff of office, ring, mace, and crown. These insignia he takes into the sanctuary and places on a seat. Coming out again, he strikes the king across the face. He now leads him into the sanctuary and pulling him by the ears, forces him to kneel before the god. The king utters the formula:

I have not sinned, Lord of the lands,

I have not been negligent of your godhead.

I have not destroyed Babylon,

I have not ordered her to be dispersed.

I have not made Esagil quake,

I have not forgotten its rites.

I have not struck the privileged citizens in the faces,

I have not humiliated them.

I have paid attention to Babylon,

I have not destroyed her walls…

He leaves the sanctuary. The šešgallu replies to this with an assurance of Bel’s favor and indulgence towards the king: “He will destroy your enemies, defeat your adversaries,” and the king regains the customary composure of his expression and is reinvested with his insignia, fetched by the šešgallu from within the sanctuary. Once more he strikes the king across the face, for an omen: if the king’s tears flow, Bel is favorably disposed; if not, he is angry.

26 A. J. Heschel, Prophets, p. 31. More generally, this attitude opposes Alma’s description of the distinctive traits of any who are desirous to be called God’s covenant people in Mosiah 18:8–9 (“willing to bear one another’s burdens, that they may be light; … willing to mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort”; cf. D&C 42:45). This covenantal sympathy turns out later to be a sort of imitatio dei, as God states, “I know of the covenant which ye have made unto me; and I will covenant with my people and deliver them out of bondage. And I will also ease the burdens which are put upon your shoulders, that even you cannot feel them upon your backs, even while you are in bondage; and this will I do that ye may stand as witnesses for me hereafter, and that ye may know of a surety that I, the Lord God, do visit my people in their afflictions” (Mosiah 24:13–14, emphasis added). Note also the emphasis in both Mosiah 18:9 and 24:14 on standing “as witnesses” of God through this sympathetic interaction.

27 See T. Fretheim, Suffering, especially chapter 10, “Prophet, Theophany, and the Suffering of God” (pp. 149–166).

28 Ibid.., p. 149.

29 Ibid., p. 151.

30 Some of Israel’s neighbors also held this view. Humanity’s capacity to weep as the gods did is alluded to in the Middle Egyptian Coffin Text 1130. It reads, “I have created the gods from my sweat, and the people from the tears of my eye” (M. Lichtheim, Readings, p. 132). In making this association between the creation of humanity and the tears of the god, the author is playing on the Egyptian words for “people” (rmṯ) and “tears” (rmyt), suggesting a link between the two terms (cf. H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 43, citing Hornung). Nibley cites a very close association with our Book of Moses text in a manuscript, where, in a mention of the Ugaritic Enoch, it is asked: “Who is Krt that he should weep? Or shed tears, the Good one, the Lad of El?” (cited in ibid., p. 42). With respect to Enoch as a “lad,” see Essay #3.

31 T. Fretheim, Suffering, p. 150.

32 Moses 7:20.

33 Moses 7:28-31, 37, 40.

34 Moses 7:41, 44.

35 H. Sperling et al., Zohar, Shemoth 8a, 3:22. See also the mention of the “two tears of the Holy One …, namely two measures of chastisement, which comes from both of those tears” (ibid., Shemoth 19b, 3:62).

36 Moses 7:40.

37 Ezekiel 9:3.

38 Ezekiel 11:23.

39 M. Odell, Ezekiel, p. 119.

40 Moses 7:21, 23, 27, 31.

41 Revelation 21:2.

42 P. Perkins, First and Second, p. 154, cited in B. Witherington, III, Letters, Jude 14-16, p. 624.

43 J. C. Reeves, Heralds, p. 183. Cf. R. Cameron et al., CMC, 58:6-20, p. 45.

44 Jude 1:15, citing G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 1:9, p. 142. See also 1 Enoch 5:4, 27:2, 101:3. 2 Peter 2:5 labels this same generation as “ungodly.”

45 M.-A. Ouaknin et al., Rabbi Éliézer, 22, p. 134.

46 Ibid., 22, p. 136.

47 J. C. Reeves, Heralds, p. 187. For a list of ancient sources, see ibid., p. 183, p. 200 n. 17.

48 P. S. Alexander, 3 Enoch, 4:3, p. 258: “When the generation of the Flood sinned and turned to evil deeds, and said to God, ‘Go away! We do not choose to learn your ways’ [cf. Job 21:14], the Holy One, blessed be he, took me [Enoch] from their midst to be a witness against them in the heavenly height to all who should come into the world, so that they should not say, ‘The Merciful One is cruel! …’”

49 Moses 7:33. Cf. Isaiah 1:2-3, where Isaiah “pleads with us to understand the plight of a father whom his children have abandoned” (A. J. Heschel, Prophets, 1:80). For more on this theme, see Essay #25.

50 Job 21:14–15. Cf. Exodus 5:2, Malachi 3:13–15, Mosiah 11:27, Moses 5:16.

51 J. C. Reeves, Heralds, p. 188.

52 Ibid., p. 183.

53 F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch, A (short version), 1:2-4, pp. 105, 107.

54 See also Moses 6:35–36, where Enoch is asked to anoint his eyes with clay prior to receiving a vision (cf. John 9:6–7). When the Lord spoke with Abraham face to face, He first put His hand upon the latter’s eyes to prepare him for his vision of the universe (see Abraham 3:11–12). Joseph Smith was reportedly so touched at the beginning of the First Vision, and perhaps prior to receiving D&C 76.

With respect to the First Vision, Charles Lowell Walker recorded the following (C. L. Walker, Diary, 2 February 1893, 2:755-756, punctuation and capitalization modernized):

Br. John Alger said while speaking of the Prophet Joseph, that when he, John, was a small boy he heard the Prophet Joseph relate his vision of seeing the Father and the Son. [He said t]hat God touched his eyes with his finger and said “Joseph, this is my beloved Son hear him.” As soon as the Lord had touched his eyes with his finger, he immediately saw the Savior. After meeting, a few of us questioned him about the matter and he told us at the bottom of the meeting house steps that he was in the house of Father Smith in Kirtland when Joseph made this declaration, and that Joseph while speaking of it put his finger to his right eye, suiting the action with the words so as to illustrate and at the same time impress the occurrence on the minds of those unto whom he was speaking. We enjoyed the conversation very much, as it was something that we had never seen in church history or heard of before.

Whether meant literally or figuratively, Joseph said that his eyes were also touched prior to his receiving the vision of the three degrees of glory:

… the Lord touched the eyes of our understandings, and they were opened, and the glory of the Lord shone round about.

And we beheld the glory of the Son, on the right hand of the Father, and received of his fulness. (see D&C 76:19-20.)

As in the First Vision, the initial result of the “touch” that opened Joseph Smith’s eyes was that he beheld the Savior in His glory. The statement that they “received of his fulness” is also remarkable. Here are the corresponding verses in the poetic rendition of D&C 76:

15. I marvel’d at these resurrections, indeed!

For it came unto me by the spirit direct:—

And while I did meditate what it all meant,

The Lord touch’d the eyes of my own intellect:—16. Hosanna forever! they open’d anon,

And the glory of God shone around where I was;

And there was the Son, at the Father’s right hand,

In a fulness of glory, and holy applause.

See J. Smith, Jr. (or W. W. Phelps), A Vision, 1 February 1843, stanzas 15–16, p. 82, reprinted in L. E. Dahl, Vision, p. 297, emphasis added. Thanks to Bryce Haymond for pointing out this reference.

55 J. Smith, Jr. et al., Manuscript Revelation Books, Facsimile Edition, Revelation Book 2, 48 [verso], 27 February 1833, pp. 508-509, spelling and punctuation modernized.

56 J. C. Reeves, Heralds, p. 189, citing 4 Ezra 5:13, 20; 6:35; 2 Apoc. Bar. 6:2–8:3; 9:2–10:1; 3 Apoc. Bar. 1:1–3; and Daniel 10:2–5. He also observes that weeping is a component of ritual mourning (see Deuteronomy 21:13).

57 The two accounts of Enoch mentioned previously can be profitably compared to the experience of Lehi who, “because of the things which he saw and heard he did quake and tremble exceedingly,” and “he cast himself upon his bed, being overcome with the Spirit” (1 Nephi 1:6-7). Whereupon the heavens were the opened to him (see 1 Nephi 1:8). See also, e.g., Baruch’s weeping for the loss of the temple (A. F. J. Klijn, 2 Baruch, 35:2, p. 632, quoting Jeremiah 9:1), which was also followed by a vision.

58 Ephesians 1:10.

59 JST Genesis 9:22.

60 Moses 7:6