Book of Abraham Insight #37

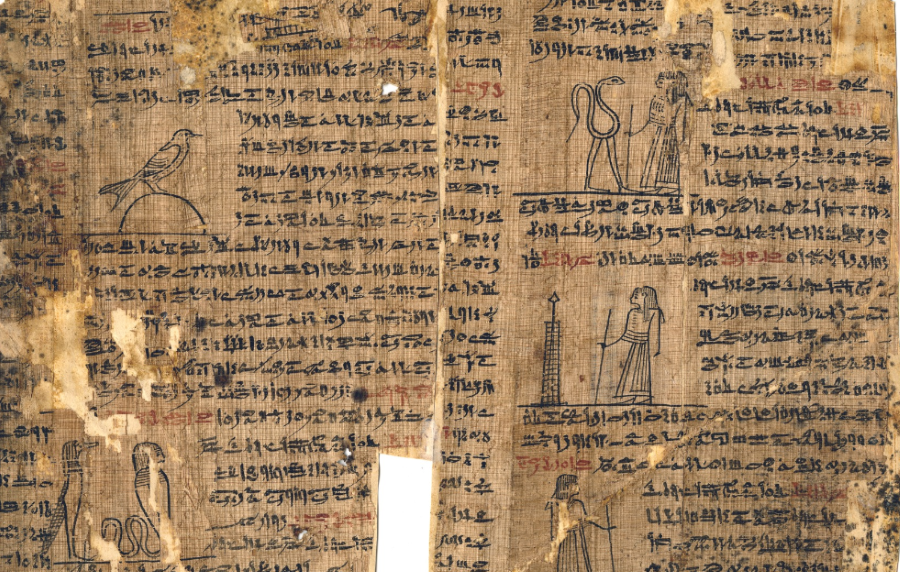

Joseph Smith acquired the Egyptian papyri associated with the coming forth and translation of the Book of Abraham in July 1835. From historical evidence and the papyrus fragments that were returned to the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in November 1967,1 we can piece together a profile of what papyri Joseph Smith is known to have possessed.

The Book of Breathings of Hor (P. Joseph Smith I, X–XI)2

One of the texts that came into Joseph Smith’s ownership was a copy of a text known today as the Book of Breathings (what the ancient Egyptians called the šˁyt n snsn; translated variously as “Document of Breathing” or “Letter of Fellowship”3). The purpose of this text, which the Egyptians believed had been written by the goddess Isis (and so was called, in full, “The Document of Breathing Made By Isis for Her Brother Osiris”; šˁyt n snsn ỉr·n Ἰst n sn·s Wsir), “was to provide the deceased with the essential information needed to be resurrected from the dead and attain eternal life with the gods in the hereafter.”4 Indeed, as the text itself explicitly says, its purpose was to cause the deceased’s “soul to live, to cause his body to live, to rejuvenate all his limbs again, so that he might join the horizon with his father, Re, to cause his soul to appear in heaven as the disk of the moon, so that his body might shine like Orion in the womb of Nut.”5

Today there are thirty-three extant copies of the Book of Breathings Made By Isis.6 “While all extant copies of the . . . Document of Breathing are very similar, no two are exactly identical.”7 The known copies belonged almost exclusively to members of families of the priesthood of Amun-Re at the Karnak Temple in Thebes, “which suggests the text might be associated with that office.”8 The copy of this text that Joseph Smith owned belonged anciently to an Egyptian priest named Hor (Ḥr) or Horos (in Greek) and is quite probably the oldest known copy (dating to circa 200 BC).9 Thanks to the work of Egyptologists since the rediscovery of the Joseph Smith Papyri, we know quite a bit about Hor and his occupation as a priest that has direct bearing on the Book of Abraham.10

The Book of the Dead of Tshemmin (P. Joseph Smith II, IV–IX)

Another papyrus scroll that came into Joseph Smith’s possession was a text owned anciently by a woman named Tshemmin (tȝ-šrỉt-[nt]-Min) or Semminis (her Greek name).11 “Semminis’s scroll contained a Book of the Dead. Originally a very long scroll, it was greatly reduced, and only fragmentary pieces ever reached Joseph Smith.”12 This copy of the Book of the Dead dated to probably sometime during the third to second century BC.13 The Book of the Dead is the name given by modern Egyptologist to a collection of writings called by the ancient Egyptians “Utterances of Coming Forth By Day” (rȝw nw prt m hrw).14 Among other purposes, this text “served as a protection for the bearer. It describes its purpose as aiding the spirit in becoming exalted, ascending to and descending from the presence of the gods, and appearing as whatever wanted, wherever wanted.”15

Although the Book of the Dead is often (and understandably) referred to as a “funerary text,” Egyptologists now recognize that this text served non-funerary purposes.16 For example, the Book of the Dead had a connection to the ancient Egyptian temple which may have significant implications for the Book of Abraham and for the Latter-day Sant temple endowment ceremony.17 “The sections of Semminis’s Book of the Dead in the Joseph Smith Papyri cover part of the introductory chapter, some of the texts dealing with Semminis’s being able to appear as various birds or animals, texts allowing her to board the boat of the supreme god and meet with the council of the gods, texts providing her with food and other good things and making her happy, and a text asserting her worthiness to enter into the divine presence.”18

The Book of the Dead of Neferirnub (P. Joseph Smith IIIa–b)

Joseph Smith also possessed a papyrus fragment that contained a section of the Book of the Dead that belonged to a woman named Neferirnub (Nfr-ỉr-nbw).19 This copy of the Book of the Dead probably dates to sometime during the first century BC to the first century AD.20 The surviving fragment contains “a portion of the vignette of chapter 125” of the Book of the Dead.21 This section of the Book of the Dead portrays a judgment scene which “shows the deceased standing before [the god] Osiris with her heart being weighed in scales.”22

This portion of the Book of the Dead was being used in Egyptian temples by the time period of the Joseph Smith Papyri.23 It was also being used in the initiation and purification rituals of Egyptian priests.24 Interestingly, Oliver Cowdery described the scene portrayed in this papyrus fragment as the judgment of the dead in 1835.25

The Scroll of Amenhotep (“Valuable Discovery”)26

Another papyrus roll that Joseph Smith owned belonged to a man named Amenhotep (Ἰmn-ḥtp).27 Unfortunately, the original papyrus containing this text is not extant. It is only known from a nineteenth century copy in the handwriting of Oliver Cowdery and appears, based on the reading of one Egyptologist, to be portions of a copy of the Book of the Dead.28 Because only a few lines of hieratic Egyptian characters were copied (enough to give us the name of the owner of the papyrus and a perhaps sense of what it contained, but not much more), it is unknown to when this papyrus dates.

The Hypocephalus of Sheshonq (Facsimile 2)

Finally, Joseph Smith owned a hypocephalus that anciently belonged to a man named Sheshonq (Ššq).29 This hypocephalus was published on March 15, 1842 in the Times and Seasons as Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham.30 Unfortunately, the original hypocephalus is not extant. However, because this type of document is rare and belonged primarily to a select group of Egyptian priests and their family members, we can date Sheshonq’s hypocephalus to sometime during the Late Period to the Ptolemaic Period (circa 664–30 BC).31 The significance and purpose of the ancient Egyptian hypocephalus has already been described in a previous Book of Abraham Insight article.32

It should be remembered that this is what we currently know Joseph Smith possessed. It is possible, and indeed likely, that Joseph Smith possessed more papyri than has currently survived. What may have been contained on the portion of missing papyrus, and exactly how much papyrus is missing, are open questions that scholars are still investigating.33

Further Reading

John Gee, “The Contents of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 73–81.

Michael D. Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Thsemmin and Neferirnub: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2010).

Michael D. Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002).

Footnotes

1 Jay M. Todd, “Egyptian Papyri Rediscovered,” Improvement Era, January 1968, 12–16.

2 The numbering for the papyri used in this article follows the numbering used in Jay M. Todd, “New Light on Joseph Smith’s Egyptian Papyri,” Improvement Era, February 1968, 40–49. The papyri themselves can be viewed online at the Joseph Smith Papers Project website (“Egyptian Papyri, circa 300 BC–AD 50”).

3 For different arguments on the best translation of the title see John Gee, “A New Look at the ˁnẖ pȝ by Formula,” in Actes du IXe congrès international des études démotiques, Paris, 31 août–3 septembre 2005, ed. Ghislaine Widmer and Didier Devauchelle (Paris: Institut Français D’Archaéologie Orientale, 2009), 136–138; Foy David Scalf III, Passports to Eternity: Formulaic Demotic Funerary Texts and the Final Phase of Egyptian Funerary Literature in Roman Egypt (PhD diss., The University of Chicago, 2014), 19–27.

4 Michael D. Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002), 14.

5 Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings, 28; see additionally Mark Smith, Traversing Eternity: Texts for the Afterlife from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009), 462–478.

6 Marc Coenen, “Owners of the Document of Breathings Made by Isis,” Chronique D’Egypt 79, no. 157–158 (2004): 59–72.

7 Marc Coenen, “The Ownership and Dating of Certain Joseph Smith Papyri,” in Robert K. Ritner, The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri, A Complete Edition: P. JS 1–4 and the Hypocephalus of Sheshonq (Salt Lake City, UT: The Smith–Pettit Foundation, 2011), 58.

8 John Gee, “Book of Breathings,” in The Pearl of Great Price Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 69.

9 Marc Coenen, “The Dating of the Papyri Joseph Smith I, X, and XI and Min Who Massacres His Enemies,” in Egyptian Religion: The Last Thousand Years, Part II: Studies Dedicated to the Memory or Jan Quaegebeur, ed. Willy Clarysse, Antoon Schoors, and Harco Willems (Leuven: Peeters, 1998), 1103–1115; Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings, 3.

10 See Pearl of Great Price Central, “The Ancient Owners of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” Book of Abraham Insight #14 (October 8, 2019).

11 Michael D. Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2010), 5.

12 John Gee, “The Contents of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 76.

13 Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub, 7.

14 Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub, 1. For an accessible yet fairly comprehensive overview of the Book of the Dead, consult Foy Scalf, ed., Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt (Chicago, Ill.: The Oriental Institute, 2017).

15 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 76.

16 John Gee, “The Use of the Daily Temple Liturgy in the Book of the Dead,” in Totenbuch—Forschungen: Gesammelte Beitrage des 2. Internationalen Totenbuch—Symposiums 2005, ed. Burkhard Backes, Irmtraut Munro, and Simone Stöhr (Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006), 73–86; Alexandra Von Lieven, “Book of the Dead, Book of the Living: BD Spells as Temple Texts,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 98 (2012): 258–259.

17 See Hugh W. Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2005); Stephen O. Smoot and Quinten Barney, “The Book of the Dead as a Temple Text and the Implications for the Book of Abraham,” in The Temple: Ancient and Restored, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry, Temple on Mount Zion Series 3 (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation and Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2016), 183–209.

18 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 76.

19 Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub, 57.

20 Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub, 57.

21 Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub, 57.

22 Rhodes, Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub, 57.

23 Von Lieven, “Book of the Dead, Book of the Living,” 263–264.

24 Robert K. Ritner, “Book of the Dead 125,” in The Context of Scripture: Volume II, Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World, ed. William W. Hallo (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 60; John Gee, “Prophets, Initiation and the Egyptian Temple,” Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 31 (2004): 101.

25 “Egyptian Mummies—Ancient Records,” Messenger and Advocate 2, no. 3 (December 1835): 236.

26 Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2018), 27–41. This text can be viewed online at the Joseph Smith Papers Project website (“‘Valuable Discovery,’ circa Early July 1835”).

27 John Gee, A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 10–13; Ritner, The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri, 209–213.

28 Jensen and Hauglid, The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 27. Ritner, The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri, 209, misleadingly describes the document as Joseph Smith’s “hand copy.” In fact, besides his signature on the front cover, Joseph Smith’s handwriting does not appear in the “Valuable Discovery” notebook. The English text and, in the judgment of Jensen and Hauglid, “likely” the hieratic characters are in the hand of Oliver Cowdery.

29 Michael D. Rhodes, “A Translation and Commentary of the Joseph Smith Hypocephalus,” BYU Studies 17, no. 3 (Spring 1977): 260–262; Michael D. Rhodes, “The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus…Twenty Years Later,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1997).

30 “The Book of Abraham,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 10 (March 15, 1842): [721].

31 Tamás Mekis, Hypocephali, PhD diss. (Eötvös Loránd University, 2013), 1:12, 2:122.

32 Pearl of Great Price Central, “The Purpose and Function of the Egyptian Hypocephalus,” Book of Abraham Insight #30 (January 13, 2020).

33 For different perspectives and arguments on the subject of how much papyri is missing, and what was potentially contained thereon, see John Gee, “Some Puzzles from the Joseph Smith Papyri,” FARMS Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 117–123; Andrew W. Cook and Christopher C. Smith, “The Original Length of the Scroll of Hôr,” Dialogue 43, no. 4 (2010): 1–42; “Formulas and Faith,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 1 (2012): 60–65; Christopher C. Smith, “‘That which Is Lost’: Assessing the State of Preservation of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 31, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2011): 69–83; Kerry Muhlestein, “Papyri and Presumptions: A Careful Examination of the Eyewitness Accounts Associated with the Joseph Smith Papyri,” Journal of Mormon History 42, no. 4 (October 2016): 31–50.